Dignified Care?

Adjacent questions in a time of Pandemic by Fatimah Tuggar

I have received requests to respond to the pandemic. These requests are appropriate. Thank you for this invitation. While this is a global moment, we have distinctly different local experiences. I am lucky and grateful to personally have the option to shelter in place, though I am mindful that many do not have this possibility. I am choosing to be present, yet looking beyond to a time when we will be more connected beyond the desperate privileges that disconnect us.

The quality of our thinking is done in the moment and over time. I think it may not yet be a time for me to respond artistically in a meaningful way. Any response I have right now is likely to be reactive, not reflective. Therefore, I chose to look back to a work from 2005, Dignified Care in which I had started to ask questions that may be relevant to our current conditions. Both artistic practice and other types of knowledge require risk-taking. These risks differ but are all necessary for human quests. The risk of creative exploration is evident in both teaching and learning. I therefore also share the work of my former student, Rebecca Baccardax's Weapons of Mass Distribution from 2015.

I have long held the position that my responsibility as an artist is to ask questions. Even if I do not have answers and they may cause temporary discomfort to others and myself. I first went on the record publicly in the 2001 publication of Tokyobook 2 by Palais de Tokyo, Paris, in which artists were asked, "What the role of the artist is today?" To this end of inquiring without answers but with the hope of better understanding and exploring “an alternative imaginary.” An alternative imaginary is how I explain my approach to making through imagining how we can create tangible change in the world with the resources we currently have. I will take you through some of my parallel thoughts and ideas in making Dignified Care.

Fatimah Tuggar

born 1967

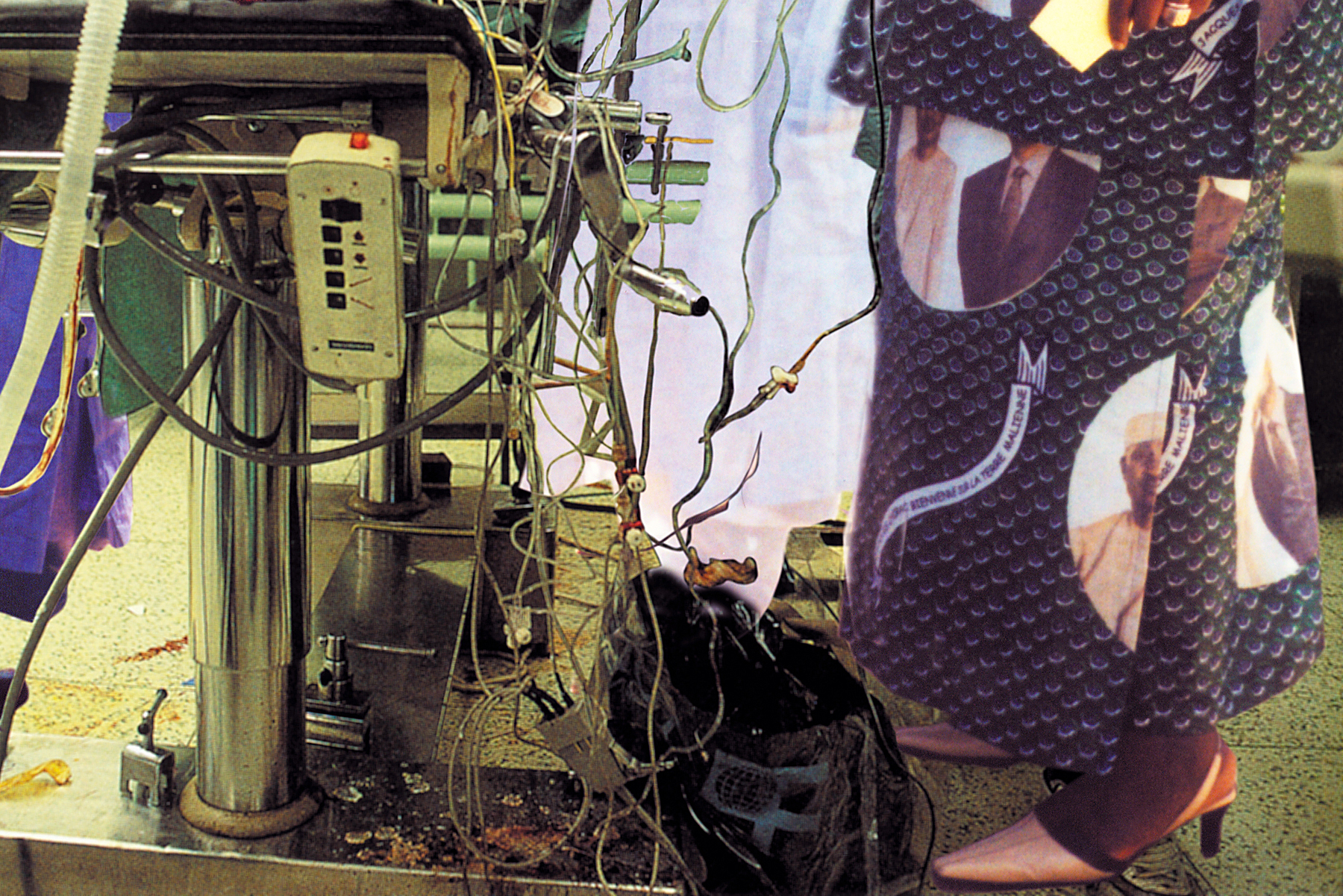

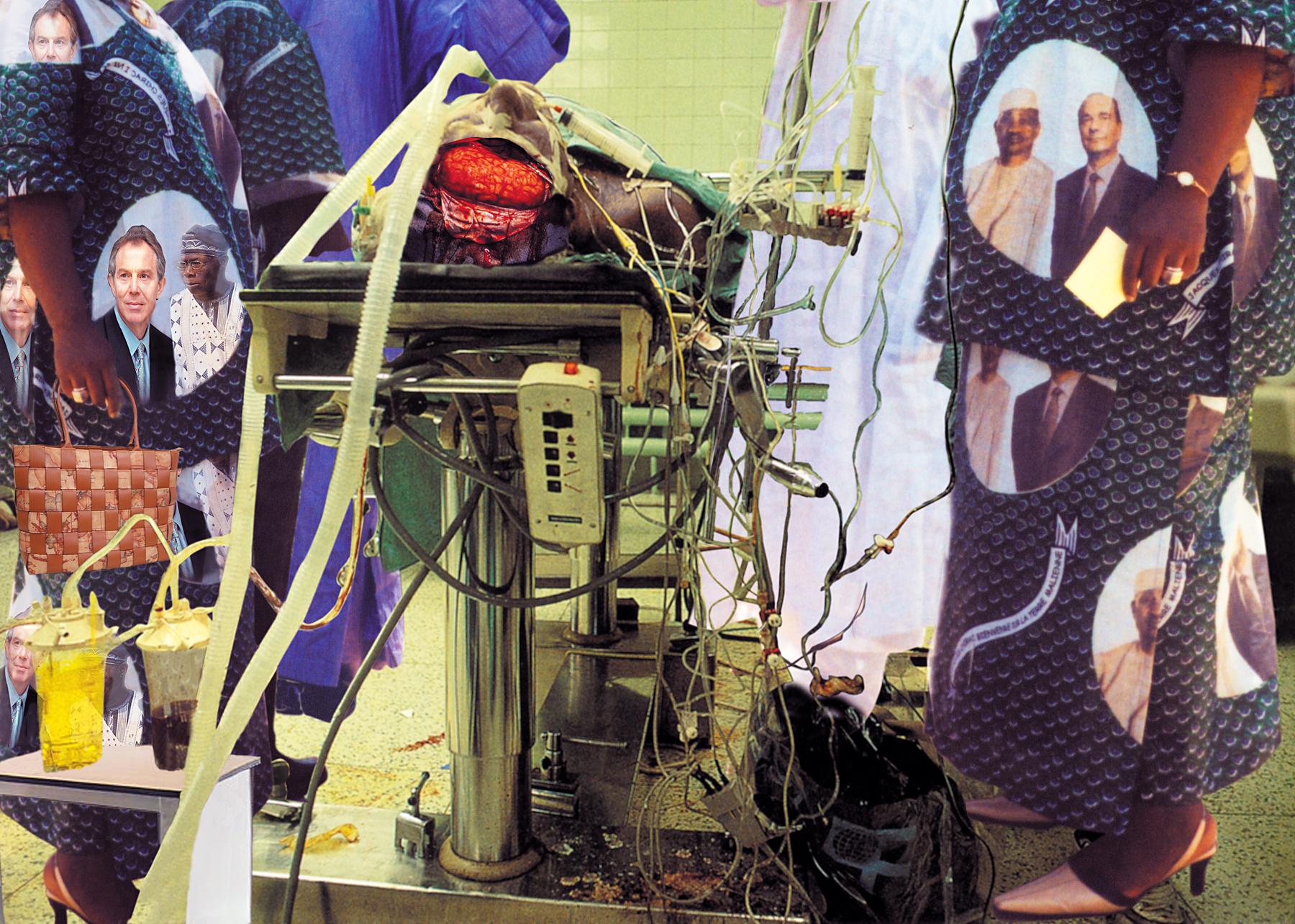

Dignified Care, 2005

Courtesy of BintaZarah Studios

computer montage, inkjet on vinyl, print size 170 x 121 cm / 67 x 48 inches

In Dignified Care, we see an image of a person during brain surgery with visitors standing around the patient. Like most of my montages, this artwork is intended to be viewed as a slice of actuality. It is cropped so that the only head present is that of the patient. The other heads (left to right) are those of elected leaders of the United Kingdom, Nigeria, Mali, and France in the year the image was made. These figureheads are present as textile motifs on clothing. The immediate questions are: How far has medicine evolved since the 19th century? What are local and global leaders doing for those without the ability to access healthcare? Is health intended only for the rich? In the time of necrocapitalism, can we genuinely claim to care about the life and dignity of all people?

In a recent quarantine call with community organiser Michael Lightsmith, he stated that: "We all experience injury and risk within the social systems we find ourselves. Though we are not all sharing the same suffering.” So, I struggle to understand why we don't rethink global health equity and consider how health intersects with social, economic and environmental justice. It seems that our world approach to medicine is one that is still colonial. The colonialists were primarily concerned with diseases spreading from the natives to the colonial masters or today, from the poor to the affluent communities. Is it a coincidence that medical care and loss of life can directly be tied to class and race? The focus is not on prevention which will require addressing systemic injustices for those living with poverty, racism and environmental decline. Care, if any, for the working poor is triaged, enough so that you are alive to return to work for the "master," corporation or state for benefitting the currently privileged. Should life be lived perpetually in a state of survival without thriving? Is misery the only way to make profits?

We indeed can all be infected by viruses, no one is above death or illness. But clearly, other factors matter to maintain wellbeing. Such as a national approach of taking care of everyone and our sick; preventative medicine that includes eradication of diseases caused by the stress of poverty, hunger, homelessness, incarceration, systemic racism, bigotry and mental and emotional trauma. We need a comprehensive, multifaceted approach.

If we have learnt anything from the pandemic, it is how seriously interconnected we all are on our planet, without imposed internal and external borders or ethnonational states. What happens to any of us happens to all of us. Yesterday's medical approach to finding cheap solutions or testing on the dispossessed or strangers in distant lands and local disenfranchised communities, the status in quo, is unacceptable. We must shift our social, economic and political systems to address these disparities or we will not survive.

These systems will inescapably collapse. Consumerism is a system that eats itself. If there is no one left alive to work for the corporations or be governed or exert power over, then what?

Our water and air are resources we share regardless of geography. This moment has emboldened monoracial politics led by megalomaniac heads of states. Luckily, moments of light come from social activists speaking truth to power. The energy of compassion and kindness some are sharing. As my brother, Usman Tuggar shares with my little nephews who keep asking when the stay at home order will be lifted in Abuja. "The planet is a living entity, and it is taking a well-earned rest after centuries of poking, we cannot rush that." Yes, air quality has improved. Can this be seen as proof that an environmentally conscious way of life is possible for all of us?

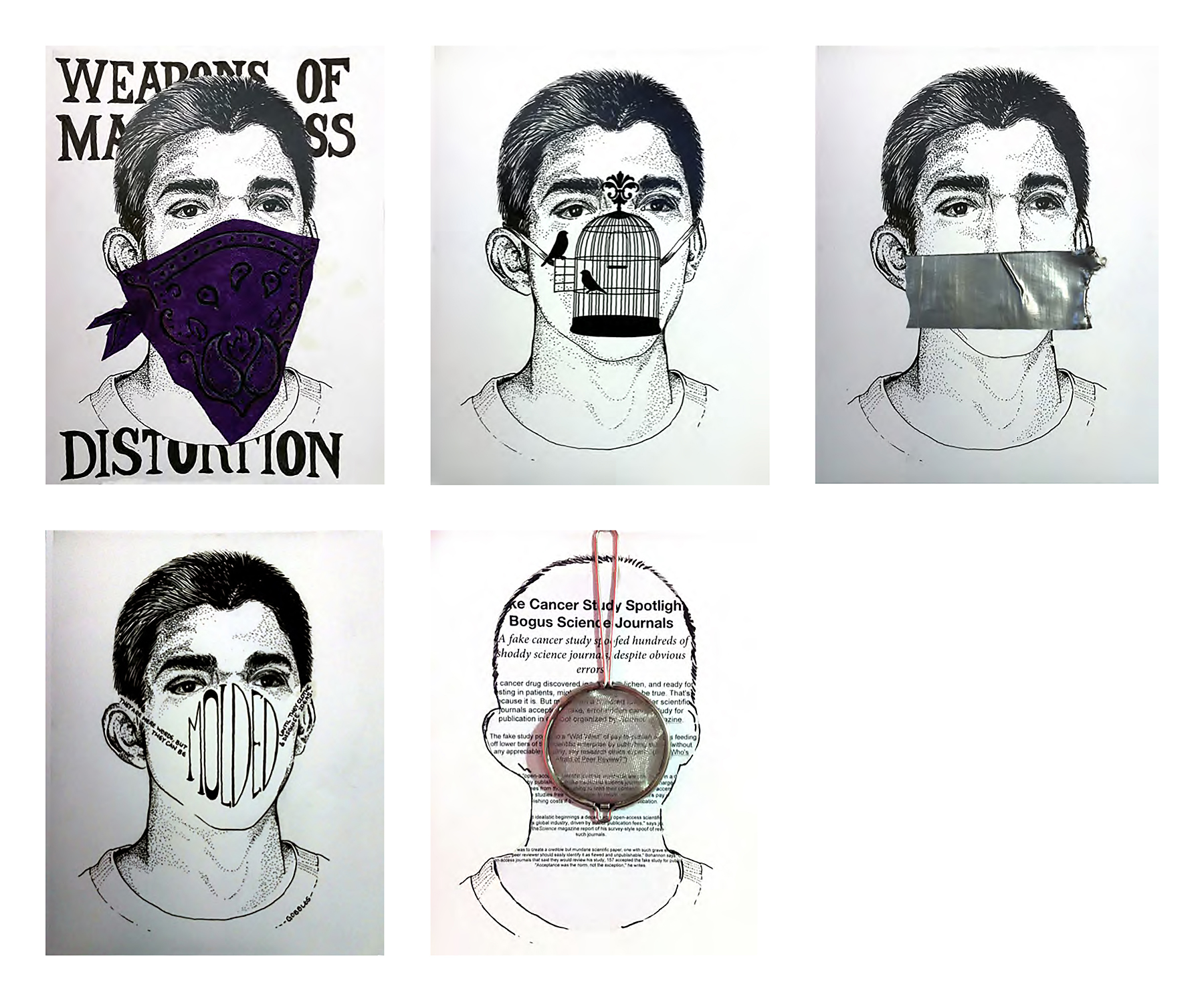

Rebecca Baccardax

Weapons of Mass Distribution, 2015

mix media-collage

During my many days home, I started spending time looking at former students' artworks wondering if and hoping that they are healthy and safe. If they are well, even if they are not making, I hope they are thinking. At a minimum, my wish for them is to come up with ideas, and explore the many tangents that arise through drawings and visual discursive formations. Because art is a practice, we must keep our minds thinking and nurture our curiosities. I came across this image by Rebecca Baccardax, the kind of student I call "art warrior," thoughtful, determined, energetic, and socially conscientious.

Our new solutions must be imaginative and beyond the limitations and misrepresentation of our so-called "decision-makers.” For example, while I am privileged to practice and advocate for quarantine, I wonder what demographics were considered for the guidance of social distancing, handwashing and mask- wearing? Does this include societies where families live in community or family compounds with multigenerational or extended families, or those in refugee camps, the homeless or those without water? What about those in urban centres where the working poor, disabled, and immigrant workers, who are likely to be housing-disadvantaged and crowded together to service the vital labour force? How can we involve people living under different circumstances to make the most effective decisions for all? Now the shortsighted consequence of the neocolonial borders of us and them has again proven dangerous and unsustainable. For those who survive the pandemic, it is crucial to insist on change towards a more equitable and ethical health system of prevention, testing and care not only for those who can afford it. Fortunately, dignity, and agency cannot be given or taken by others.

I respectfully acknowledge that this is written on May 5, 2020, on the traditional land of the Osage and Kaw Peoples past and present. This is a gesture of my commitment to learn and be a better partner in the stewardship of the lands we inhabit.

Artist bio

Fatimah Tuggar was a featured artist in the Spencer Museum’s 2019–2020 exhibition knowledges. For Tuggar’s commission she created a new installation Lives, Lies, and Learning that explored the persistent inequalities and bullying that occur at institutions of higher education. Through the use of holograms, Tuggar presented scripts from these experiences that exposed equitable access to education and opportunity as a façade. Tuggar participated in the 2019 Integrated Arts Research Initiative (IARI) colloquium and Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities (a2ru) national conference. She was also a contributor to the Museum’s publication Inquiries.