SEEING

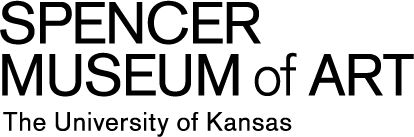

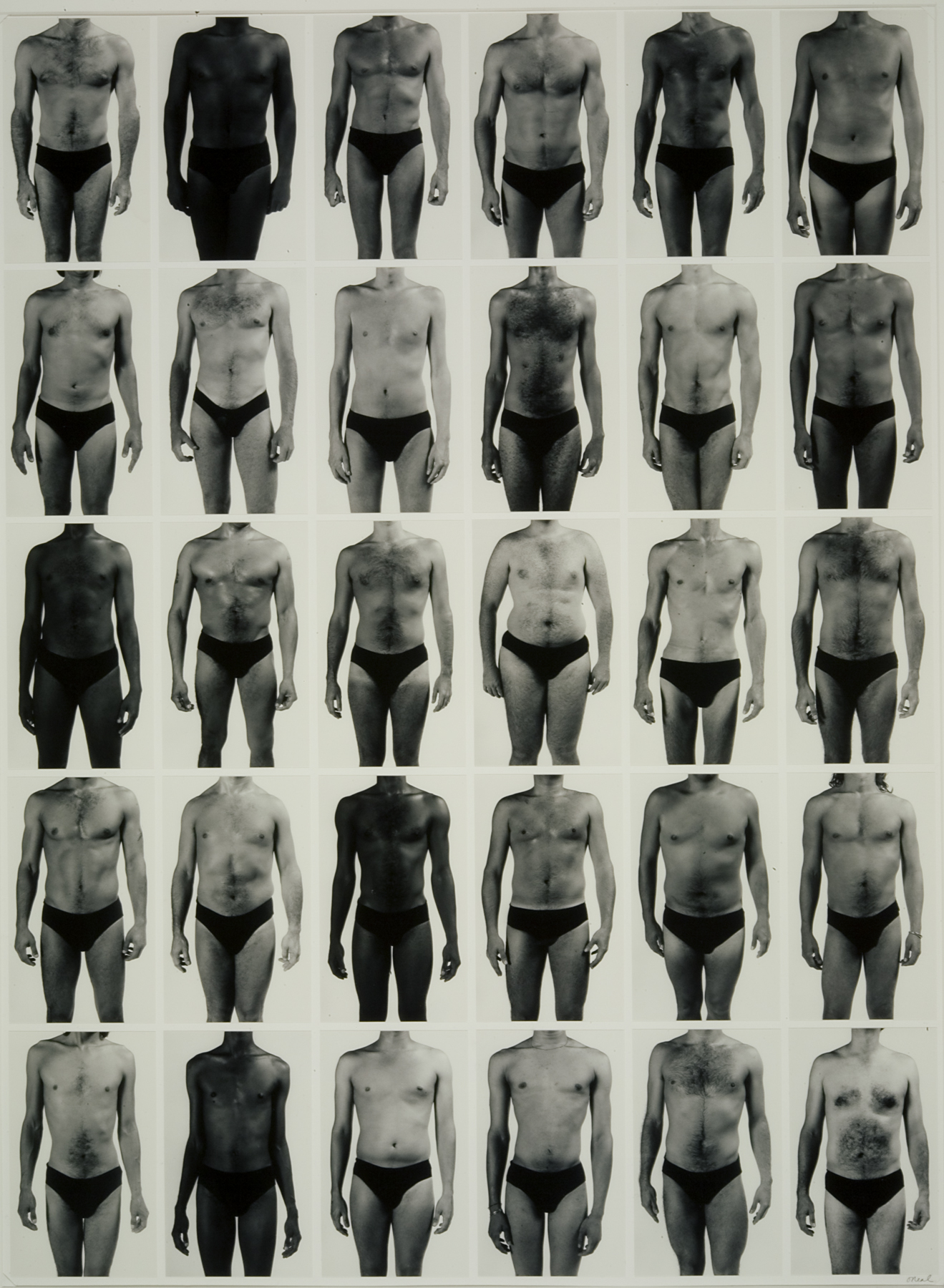

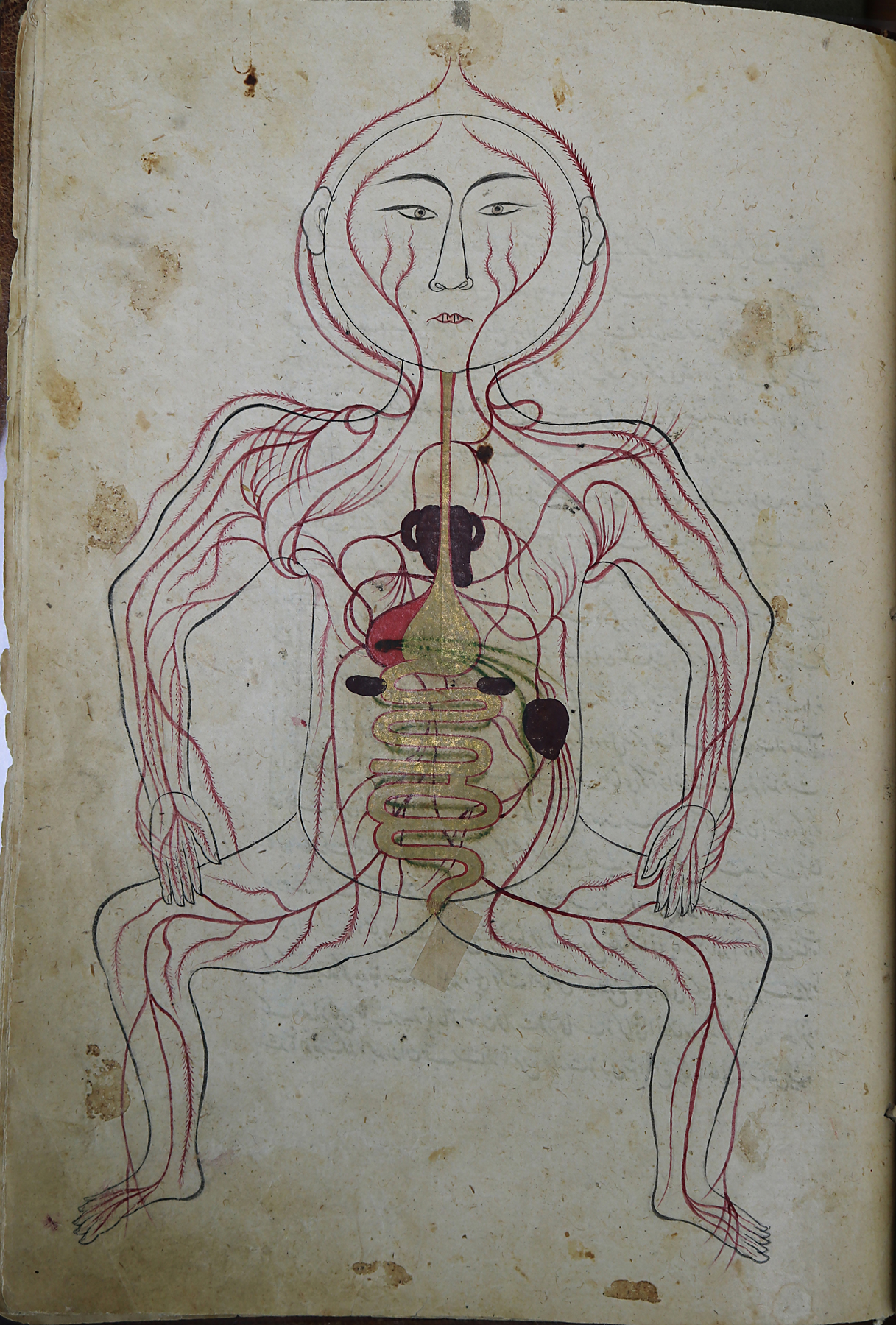

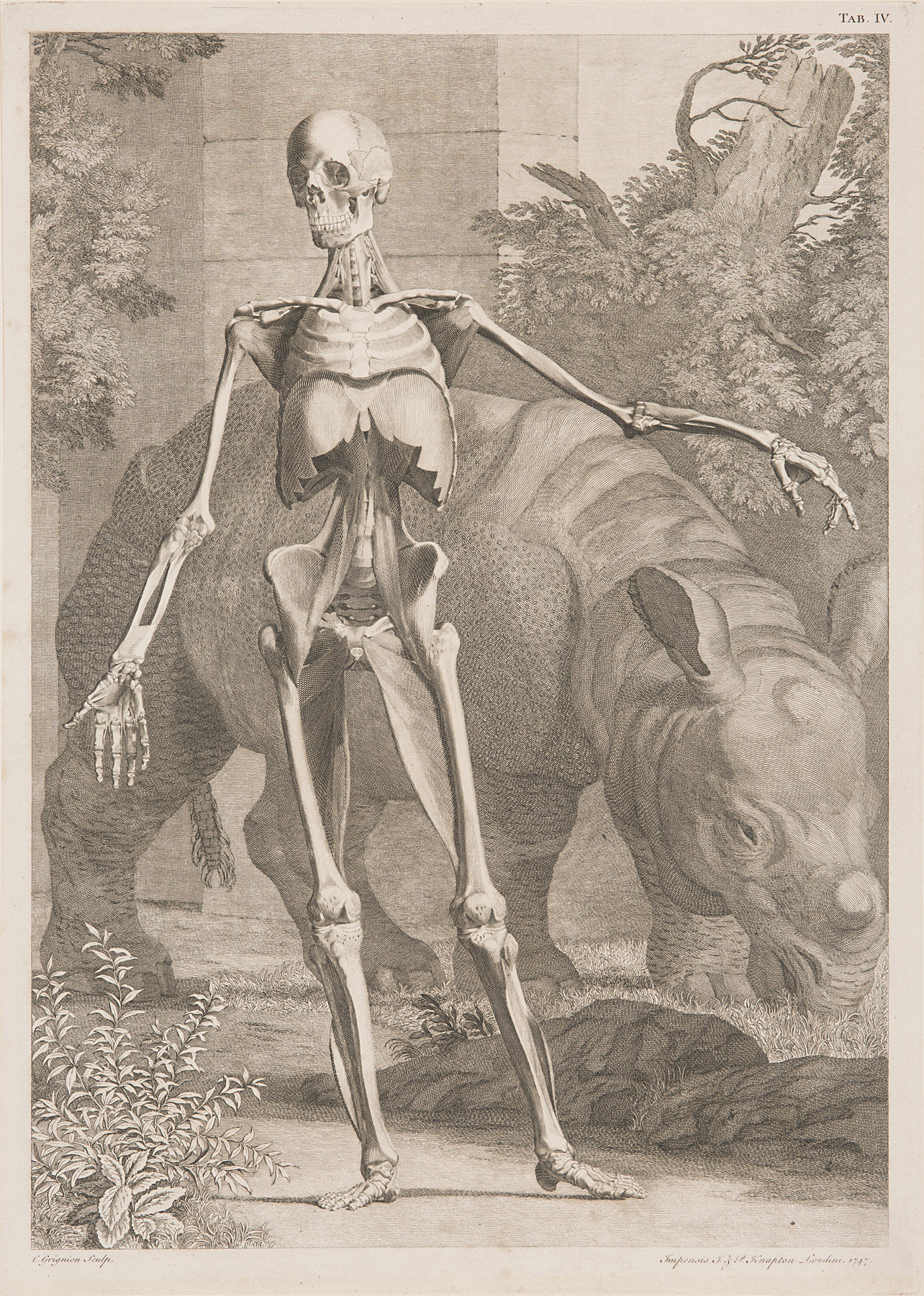

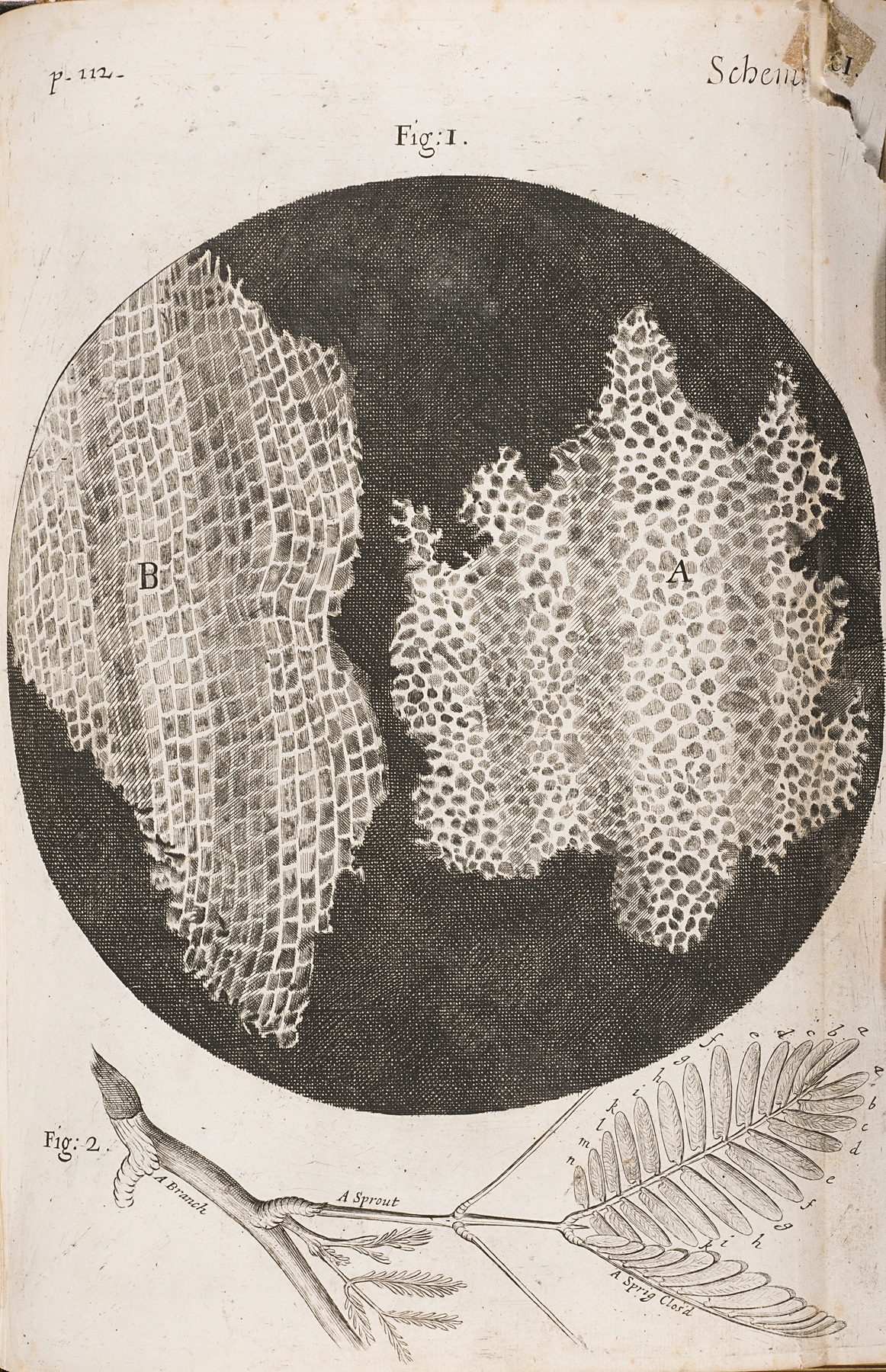

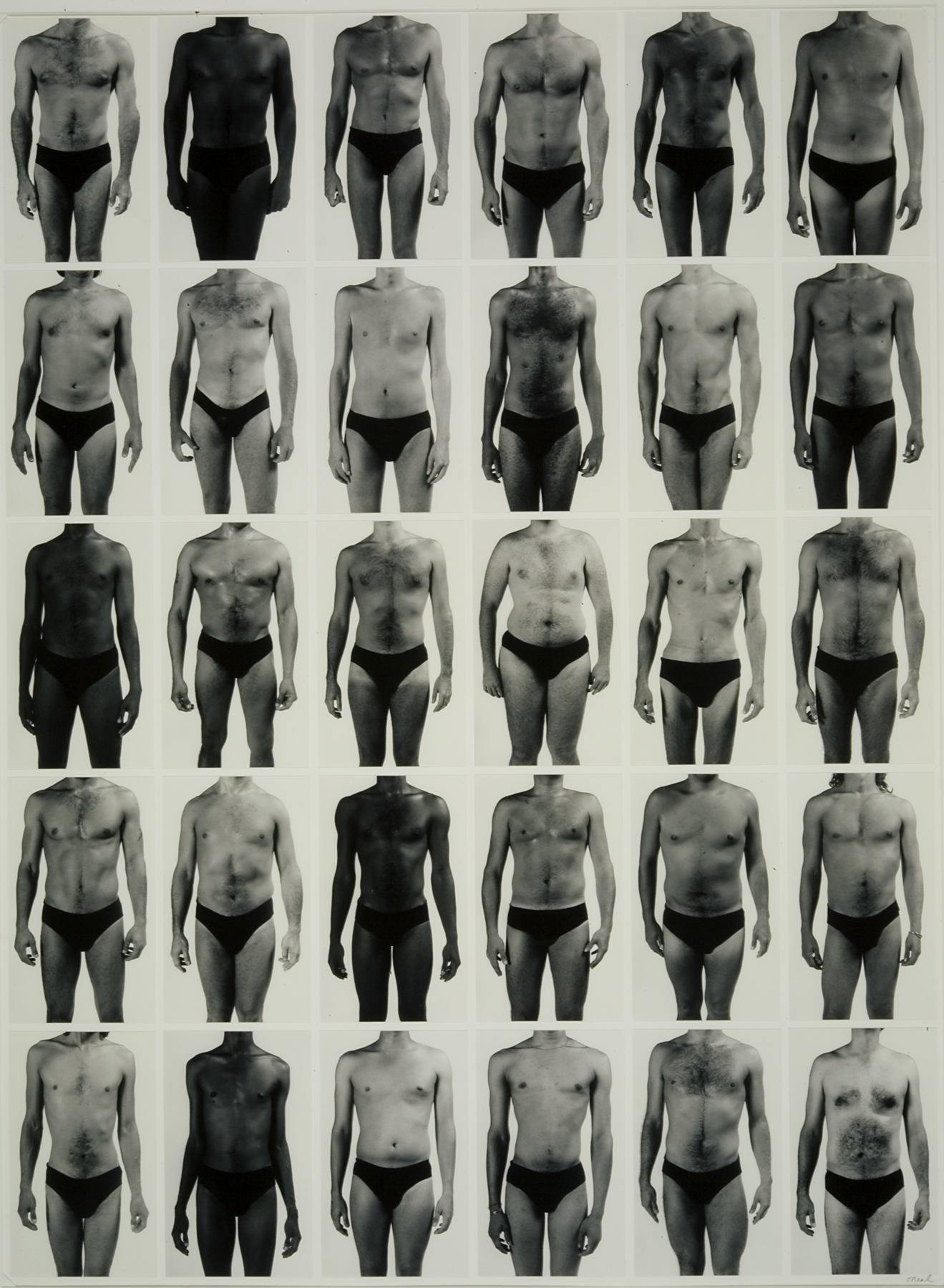

The scientific study of human anatomy began as early as 1600 BCE, when Egyptians compiled the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, a written text demonstrating knowledge of several organs and bodily systems and named after the dealer who bought the text in 1862. However, many world religions prohibited dissecting or portraying the human form, slowing the development of a visual language for depicting its anatomy for centuries. The works in this section trace this history through important anatomical illustrations—from a 14th-century Persian manuscript to the revolutionary work of Andreas Vesalius in the 1500s; from the earliest recordings of the human pulse as a waveform to photographic documentation of HIV-positive bodies in the 1980s.

All of these reflect the capacity of anatomical illustration—and the medical gaze more broadly—to simultaneously distance and connect, anonymize and personalize. The representation of the human body in medical contexts raises many interrelated questions: How have techniques for seeing the body changed through time, and how have they influenced our understandings of the human body? Can art play a more significant role in our understandings of the body beyond illustration?

The scientific study of human anatomy began as early as 1600 BCE, when Egyptians compiled the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, a written text demonstrating knowledge of several organs and bodily systems and named after the dealer who bought the text in 1862. However, many world religions prohibited dissecting or portraying the human form, slowing the development of a visual language for depicting its anatomy for centuries. The works in this section trace this history through important anatomical illustrations—from a 14th-century Persian manuscript to the revolutionary work of Andreas Vesalius in the 1500s; from the earliest recordings of the human pulse as a waveform to photographic documentation of HIV-positive bodies in the 1980s.

All of these reflect the capacity of anatomical illustration—and the medical gaze more broadly—to simultaneously distance and connect, anonymize and personalize. The representation of the human body in medical contexts raises many interrelated questions: How have techniques for seeing the body changed through time, and how have they influenced our understandings of the human body? Can art play a more significant role in our understandings of the body beyond illustration?