The human body has been a source of enduring fascination and intense study for millennia, and artists have contributed significant insight and knowledge in this arena. Some of the artists represented in this section focus on the therapeutic value of art-making in alleviating and destigmatizing mental illness, while others illustrate how embodied experiences can be communicated through artistic practice. Many have engaged in sustained and meaningful collaborations with medical professionals. Their work demonstrates the creative potential artists bring to conversations about vital but contested issues in healthcare today, including vaccination, organ transplantation, and barriers to access.

These works of art raise important questions. How can techniques and tools used in Western medicine be integrated into art-making, and, conversely, how might artistic practice inform scientific thinking toward the advancement of patient care and health outcomes? What kind of medical research is currently being undertaken, and how is it made visible and accessible to the public and patients?

How can expressing our bodily experiences contribute to an inclusive dialogue about health, illness, and wellbeing?

The Anatomy Table, Sean Caulfield

Caulfield label

Sean Caulfield produced The Anatomy Table as part of the transdisciplinary project <ImmuneNations>, which focused on researching the diverse cultural ideas around the safety and efficacy of vaccines. This series of prints combines two layers of images. The first consists of illustrations by the renowned 16th-century anatomist Andreas Vesalius, whose work you can explore in the section on Seeing. The title of the work and presentation of the central figure lying flat and exposed further recall the careful dissections Vesalius is known for performing in anatomy theaters. The second layer comprises Caulfield’s own fantastical drawings inspired by scientific descriptions of viruses. By juxtaposing these two sources and uniting them visually, Caulfield invites us to consider the problematic divide between scientific/objective/empirical and cultural/emotional/artistic representations of the body.

Pelt, Ingrid Bachmann

Audio

Bachmann label

The human body is a central focus of much of Ingrid Bachmann’s work. In Pelt, she raises questions about the relationship of our bodies to technology. Originally one of six animal-like kinetic sculptures, this work seeks to humanize technology through rhythmic inhalations and exhalations. Its organic, almost sentient movements encourage us to consider where our bodies end and where technology begins—a question not only relevant in the medical sciences, where implants, transplants, prostheses, and other procedures can permanently alter our bodies—but also in day-to-day life as we interact with technologies that can at once connect and alienate us from one another.

Heart and Mind, Andrew Carnie

Carnie label

The pages of this book are laser cut with two images of a human heart, inspired by Andrew Carnie’s research as part of Hybrid Bodies, a transdisciplinary team investigating the social and psychological dimensions of heart transplantation in Canada. Carnie intends for the image to be legible as a human heart, but also allow for the viewer to question what might be missing, referencing the anonymity that accompanies organ transplants. The pages are stitched along the side to recall the ways that new organs are stitched into a recipient’s body.

Chromo-Therapy, Patrick A. Nagatani

Chromo-therapy label

Chromotherapy, which involves directing colored light at afflicted areas of the human body to cure disease, has roots in ancient Egypt and China. The practice was introduced in the United States in the 19th century as an alternative to Western medicine’s often aggressive and invasive methods. After a surgical procedure, and influenced by his close attention to color in his photography practice, Nagatani was drawn to chromotherapy treatment and pursued extensive research to learn more. In this work, he engages the ongoing debates between the supposedly objective science of Western medicine and the pseudoscience surrounding alternative healing practices such as chromotherapy.

Houdeck text

Metalsmith Holland Houdek has partnered extensively with the medical industry, including the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, MedWish International, and the Cleveland Clinic. As a result of these collaborations, Houdek recognizes the ways that medical implants save lives, but she also acknowledges that there are many who cannot access these treatments. As part of her series Of a Particular Kind, Houdek uses painstaking hand-fabrication techniques and intricate—rather than purely functional—forms to explore tensions between the well-publicized benefits of medical technologies and the unseen challenges that billions of people worldwide face in securing them. These implants seek to personalize the hardship, devastation, and futility that so many face in their efforts to improve their life through medical intervention.

The names in the titles refer to fictional patients the artist imagined, inspired by her own friends and families and stories told by people who have received implants themselves. To create the images, Houdek used Photoshop to insert her implant into x-rays that were donated, with patient permission, by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Shoulder Replacement – Mrs. Bjerk, Holland Houdek

x-ray image of Shoulder Replacement – Mrs. Bjerk, Holland Houdek

Houdek text 2

Holland Houdek suggests that medical devices and surgical tools carry conflicting messages: they can provoke fear and terror, hope for healing, and a “macabre fascination” about how they would feel when used on a living body. These sculptural pieces are also meant to elicit bodily responses in viewers and make them aware of their corporeality. Both evocative of biomedical enhancements and prostheses—Nelumbo Mastoplasty, for instance, incorporates a silicone breast implant—the works encourage viewers to visualize the implants and imagine that the correlating anatomies (heart, veins, breasts) were missing in their own bodies. For Houdek, this work also blurs past and present, existing “in the future by conceptualizing a new type of anatomy and ways to mend the body, while also gesturing to the historical genre of memento mori”–objects that serve as reminders of mortality and death, such as skulls.

Nelumbo Mastoplasty, Lotus Breast Implant Replacement Neckpiece, Holland Houdek

Device 39C, Insulin Pumps, Holland Houdek

Cardiovascular Complex, Heart and Vein Implant, Holland Houdek

Junctures of a Haphazard Kind

For the past two years, UK-based artist Andrew Carnie has worked with a network of artists in the UK to produce Junctures of a Haphazard Kind. Building from his role in the transdisciplinary project Hybrid Bodies, which examines the non-medical effects of organ transplantation on recipients and donor families, this series of collaborative works explore notions of anonymity, consent, and responsibility by inviting artists to use works of art by Carnie to create a new, hybrid piece.

Spencer Curator Cassandra Mesick Braun invited four regional artists to participate in Junctures of a Haphazard Kind based on a variety of factors, including their work with textiles and mixed media, commitment to collaborative art-making, and interest in exploring the body and embodiment through art. Their diverse contributions were undertaken during the first weeks and months of the Covid-19 pandemic.

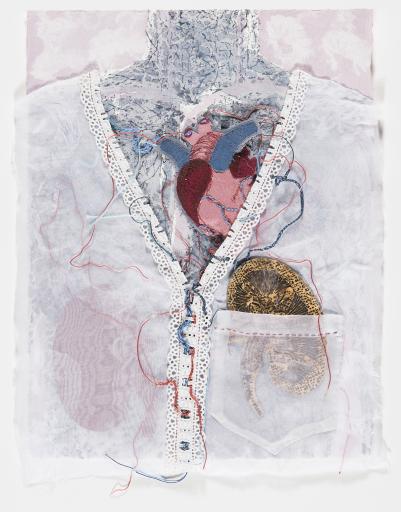

Open Heart, Mary Anne Jordan; Andrew Carnie

Plea, Mary Anne Jordan; Andrew Carnie

Junctures text

Contributing to Junctures of a Haphazard Kind prompted textile artist and University of Kansas professor Mary Anne Jordan to muse on “the fragility of life yet the amazing resiliency of our bodies to regenerate and heal…especially since this work was done during the precarious and uncertain time of a pandemic.” In these pieces, she explores metaphorical links between textiles and the body. In Open Heart, Jordan considers clothing not as a cover or protector, but rather as a disguise for the body. She deliberately chose transparent fabric to illustrate how close our flesh, blood, and organs are to the outside world. Here, clothing, imagined skin, and organs are all criss-crossed with thread and veins—words that themselves have strong links to lineage, family, and physical corporeality.

In Plea, she relates the skilled handwork required to create domestic textiles like doilies, lace, and quilts to the complex structures of the body and dexterity required to perform surgeries; here, stitches function as sutures to repair and connect.

"The skilled, intricate, and complicated handwork involved in making domestic textiles is used as a metaphor for the complex structures of the body or even the dexterity of surgery."

Mary Anne Jordan

untitled, Andrew Carnie; Nazanin Amiri Meers

untitled, Andrew Carnie; Nazanin Amiri Meers

Haphazard text 2

After working on Junctures of a Haphazard Kind, Naznin Amiri Meers reflected that she felt like she’d been entrusted with a gift. She states that the process of collaboration prompted her to reflect on care, compassion, connection, and the responsibility we should all feel toward one another—sentiments that felt particularly timely in the early spring, during the first phases of lockdowns and social distancing caused by Covid-19.

"Knowing that other artists were collaborating gave me a kind of reassurance—as if I could imagine myself sitting in the same room and working with others on such a meaningful project about generosity and caring for others in the worst times. No matter how independent we think we are, we rely on each other, and this project could not come in a better time to remind me about our mortality, our need for each other, and hope."

Nazanin Amiri Meers

Eye Heart Kidneys, Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel; Andrew Carnie

Organ Donation Operation, Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel; Andrew Carnie

Sydney text

Participating in Junctures of a Haphazard Kind prompted Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel to conduct research about organ transplantation and donation, a topic about which she had little prior knowledge. Her work references the most surprising fact she learned as part of her research: that over 80% of people on transplant lists are waiting for kidneys, more than for any other organ. Since Pursel often aims to educate viewers on complex social problems, she also repurposed a functional game of Operation, transforming Carnie’s works into an interactive experience that teaches players about organ donation.

Sydney quote

"I was surprised that kidneys are in such high demand. Over 80% of people waiting for an organ are waiting for a kidney. I didn’t know livers could regenerate. I also didn’t realize how many people are waiting for more than one organ. Now, every time I hear a story on organ donation, my ears perk up."

Sydney Jane Brooke Campbell Maybrier Pursel

untitled, Andrew Carnie; Juan José Castaño-Márquez

untitled, Andrew Carnie; Juan José Castaño-Márquez

Marquez text

Expanded media artist Juan José Castaño-Marquez was surprised by the fear he felt when faced with modifying another artist’s work, and he spent the first six weeks thinking about issues of organ transplantation and human connection abstractly, without translating his concepts into artwork. Once he overcame this paralysis, however, the process caused him to think deeply about organ donation—and the many ways humans are connected to one another. An artist who regularly explores hybridity, gender, and performance in Catholic rituals, Castaño-Márquez draws fascinating connections between organ transplantation and asks whether traces of identity, knowledge, and existence can transcend death.

"The project made me realize that there are different ways of being connected, even beyond organ donation. More simple ways of being connected, through our ideas, thoughts, and feelings."

Juan José Castaño-Márquez

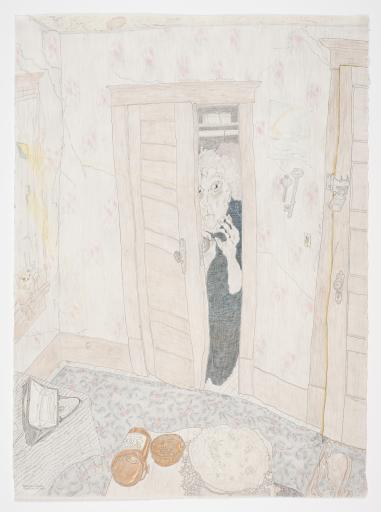

Fear, Elizabeth Layton

Layton text

Elizabeth “Grandma” Layton was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and experienced profound depression for much of her life, leading to several psychiatric hospitalizations and rounds of electroconvulsive therapy. Yet it was not these interventions but rather drawing that provided Layton with lasting therapeutic benefits. Nevertheless, her struggles with mental health often appear in her drawings. In Fear, Layton portrays herself wide-eyed and cowering in a closet. Next to her, a door is padlocked from the inside, keys hanging nearby, suggesting that the literal key to her escape from the fear is within reach, but that she is unable to grasp it. An empty prescription bottle indicates that Layton manages her condition through medication, but that it may not be effective or has worsened because she ran out of pills.