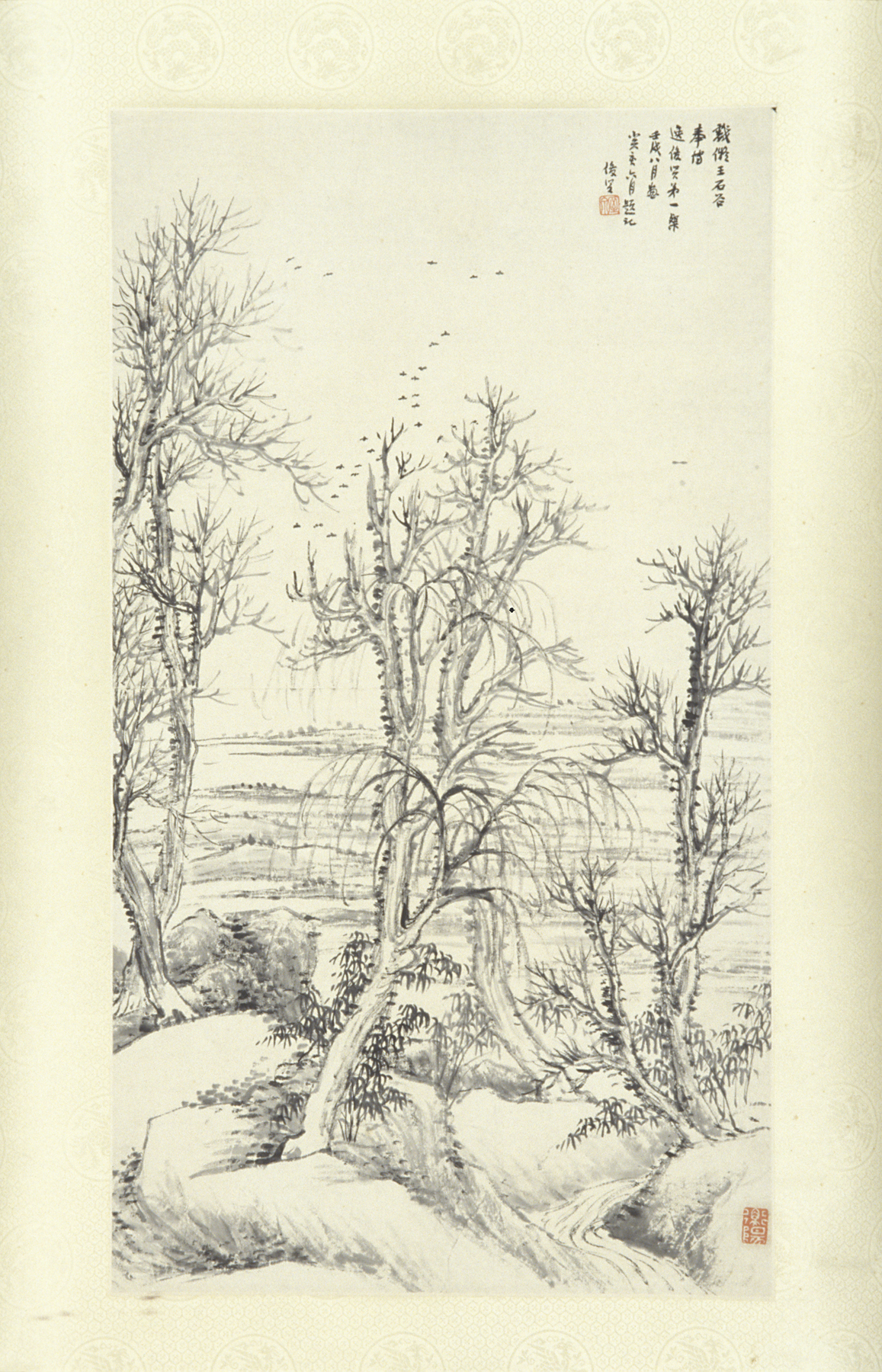

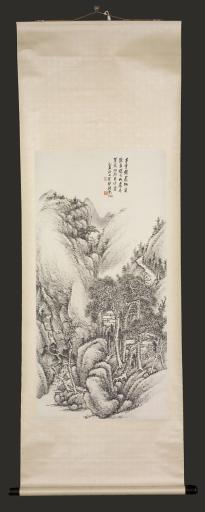

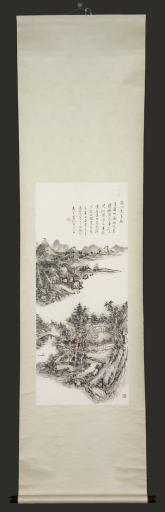

Reviving the Past: Antiquity & Antiquarianism in East Asian Art | The Boundaries of Heaven: Chinese Ink Painting in the Republican Period, 1911-1949

Exhibition Overview

As with any period of transition, the Republican era (1911-1949) was one of immense change. Political instability coupled with efforts to dramatically rethink Chinese culture, producing an embattled art world in which dynamic experimentation often clashed with the stalwart defense of tradition. The founding of the Republic in 1911, which ended two millennia of imperial governance, created a ruptured socio-political landscape.

In the north, after the failed attempt of Yuan Shikai 袁世凱 (1859–1916) to re-establish the monarchy, the Beiyang Government—a series of warlords with its capital in Beijing—served as the international representative of China. Shanghai emerged as an economic powerhouse in the region. Under a semi-colonial jurisdiction of foreign concessions, it symbolized both the embarrassing demise of China and the exciting prospect of new ideas that poured in from the West. The intellectual leader of the Republic, Sun Yat-sen 孫中山 (1866–1925), created his own regional military government in the southern city of Guangzhou. It was from here that Sun’s successor, General Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 (1887–1975), marched north in 1927 and eventually unified much of coastal China under a new Nationalist Party (KMT) government with its capital in Nanjing.

On the cultural front, intellectuals and artists energized by the New Culture Movement (1919–1929) began serious efforts to reform Chinese society. In literary circles, writers promoted the use the vernacular, “common” language (baihua) in their works. Similarly, many visual artists promoted Western realism as an effective method for promoting social change. However, not all artists took such radical measures. Rather, defenders of ink painting viewed it as a cultural resource, calling it “national painting” or guohua as part of a campaign to legitimize traditional arts as essential to the nation. This exhibition ponders the place of guohua artists during this period, and their efforts to make ink painting a viable and responsive cultural product in the quickly changing Chinese society of the early twentieth century.

This exhibition complements the later-twentieth century ink paintings in A Tradition Redefined.