The Legend of John Brown in Kansas

Intro

The print series The Legend of John Brown details the life and death of abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859) as depicted by acclaimed Black Modernist Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000). Just as Lawrence conducted extensive research on Brown to create the series, Curator Kate Meyer and graduate intern Claire Cox took research trips and gathered information to make connections between Lawrence’s prints and Kansas history. Here, Cox details how 5 of the 22 prints in Lawrence’s series have specific ties to events that occurred in Kansas.

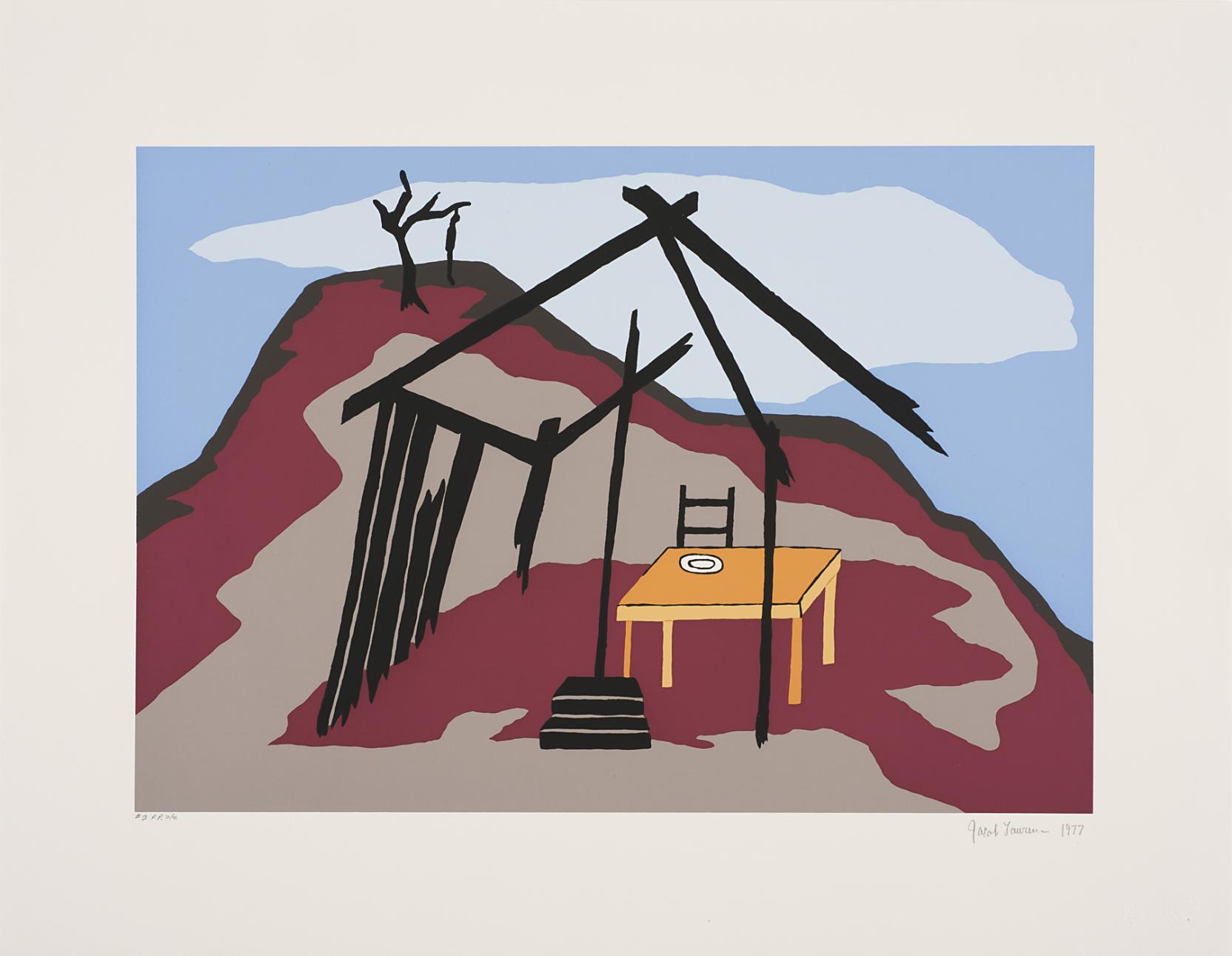

Jacob Lawrence, Kansas was now the skirmish ground of the Civil War. 1974–1977, Museum purchase: Gift of Jeff and Mary Weinberg, 2020.0068.10

Kansas was now the skirmish ground of the Civil War.

The title of this print is a quote from Franklin B. Sanborn’s The Life and Letters of John Brown (1885). According to Sanborn, John Brown achieved infamy because of the events that transpired in Kansas Territory in 1855–1856. This print foreshadows the violence and destruction that followed Brown’s arrival in Kansas. In December 1855, Brown and four of his sons helped defend Lawrence from proslavery forces during the Wakarusa War, a brief conflict triggered by the murder of a Free-State man, Charles Dow, by a proslavery settler. From this point forward, Brown assumed the title “Captain,” transforming his religious mission to abolish slavery from theory to direct action.

Jacob Lawrence, Those pro-slavery were murdered by those anti-slavery., 1974–1977, Museum purchase: Gift of Jeff and Mary Weinberg, 2020.0068.12

Those pro-slavery were murdered by those anti-slavery.

On May 21, 1856, Sheriff Samuel Jones of Douglas County led a group of 800 armed proslavery men into Lawrence, burning two newspaper offices and destroying much of the town. The next day in Washington, DC, proslavery Representative Preston Brooks physically attacked the abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner with his cane, beating him unconscious on the Congress floor. Upon hearing of both events, Brown plotted the brutal murder of five proslavery settlers, known as the Pottawatomie Massacre. Although Brown denied killing any of the victims himself, he did confess to ordering the massacre. According to Sanburn, Brown believed he was doing “God’s service.” Despite Brown’s direct involvement in the violent murders, Jacob Lawrence omitted Brown from the imagery.

Jacob Lawrence, John Brown took to guerrilla warfare., 1974–1977, Museum purchase: Gift of Jeff and Mary Weinberg, 2020.0068.12

John Brown took to guerrilla warfare.

After the Pottawatomie Massacre, John Brown traveled throughout Kansas with a small company of followers who supported the abolitionist cause. Motivated by the strong religious beliefs, Brown viewed himself as a soldier in a larger war against slavery. According to Sanborn, “Brown had taken to the prairie for guerilla warfare against the Missourians and other southern invaders of Kansas.” Following the Pottawatomie Massacre, several proslavery parties from Missourians, known as Border Ruffians, often raided Free-State homesteads. From the end of May to the beginning of June 1856, Brown and his men served as a loosely organized militia on behalf of Free-State settlers in Douglas, Franklin, and Miami Counties.

Jacob Lawrence, John Brown’s victory at Black Jack drove those pro-slavery to new fury, and those who were anti-slavery to new efforts. 1974–1977, Museum purchase: Gift of Jeff and Mary Weinberg, 2020.0068.13

John Brown’s victory at Black Jack drove those pro-slavery to new fury, and those who were anti-slavery to new efforts.

In response to the Pottawatomie Massacre, a group of proslavery forces led by Henry C. Pate conducted a manhunt for Brown. Although Brown managed to escape, Pate and his posse captured two of Brown’s sons, John Jr. and Jason. Brown gathered a company of 29 men to ambush Pate’s camp at Black Jack, near present-day Baldwin City. On June 2, 1856, Brown attacked Pate’s army of 50 proslavery Missourians. After three hours of fighting, Pate surrendered to Brown, who took Pate and 22 of his men as prisoners. In recalling the skirmish, Pate admitted, “I went to take Old Brown, and Old Brown took me.” The Battle of Black Jack escalated the sense of urgency around the slavery debate, which Lawrence portrays in one of the only prints in the series to depict active violence. As the first armed conflict between proslavery and antislavery forces, the Battle of Black Jack foreshadowed the simmering violence that would soon envelop the United States in civil war.

Jacob Lawrence, In spite of a price on his head, John Brown in 1859 liberated twelve negroes from a Missouri plantation., 1974–1977, Museum purchase: Gift of Jeff and Mary Weinberg, 2020.0068.17

In spite of a price on his head, John Brown in 1859 liberated twelve negroes from a Missouri plantation.

Throughout this series, Jacob Lawrence emphasizes that Brown’s religious beliefs motivated his efforts to abolish slavery. Shortly after the Battle of Osawatomie in August 1856, Brown left Kansas Territory and traveled east on a fundraising campaign. Brown relied heavily on financial support from the Secret Six, a group of northern men who supported Brown’s antislavery crusade. In June 1858, Brown returned to Kansas as a wanted man for his role in violent confrontations, most notably the Pottawatomie Massacre. On December 20, 1858, Brown led an ambitious raid into Missouri, intending to free slaves from several farms located just across the border. Brown and his company helped 11 enslaved African Americans liberate themselves, lending them northward along the Underground Railroad. In early January 1859, Narcissa Daniels, a member of the group gave birth to a son whom she named after John Brown. On January 14, the group arrived in Lawrence, seeking refuge with Joel and Emily Grover on their small farm. The Grover Barn still stands today near the intersection of Clinton Parkway and Lawrence Avenue.

View another story

Needlework Samplers Reveal Stories of the Past