Interview with artist Kandace Creel Falcón

Interview

What does boldness mean to you?

My mentor, Edén E. Torres, wrote a fabulous academic book published through Routledge called Chicana without Apology and that is the immediate phrase that comes to my mind when I think about boldness. To me, boldness is courageous authenticity. To embody boldness is an invitation to be one’s fullest, most authentic self no matter the context. It is a choice to forge forward with courage and authenticity in a world that seeks to make women and gender non-binary folks small. I love the idea of expressing who we are to the fullest in hopes of changing the world around us to be more accepting and loving about difference. These are values I try to embody as a visibly queer, light-skinned, mixed-race Xicanx person living in a rural place in the U.S. in these times.

How would you define feminism?

I always borrow from the late, great, feminist theorist and thinker bell hooks when I define feminism as a “movement to end sexism and other forms of oppression,” which is how she defines it in her book Feminism is for Everybody. There are so many ways to think about feminism and feminist theory, and for me, as a queer person, a gender non-binary femme, and as someone with Mexican ancestry, I’ve honed in on feminism as a calling, a political framing that is focused on ending sexism and all forms of oppression that exist because of hierarchies, binaries, and the misuse of power. I aim to challenge sexism wherever I go and in my work I am interested in complexifying what we understand as sexism, especially as it often intersects with other forms of oppression like heterosexism, classism, and racism. I/We owe a great deal to Black feminism in the way that thinkers like Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Barbara Smith, bell hooks, the Combahee River Collective and others have set the stage for us to understand sexism in its many insidious forms and in how sexism intersects other forms of oppression. This is why my definition of feminism means we take a critical lens to inform actions for dismantling all forms of oppression.

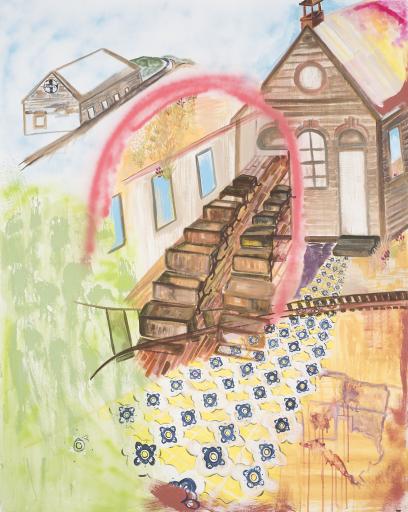

Eager to Learn , Kandace Creel Falcón

How does Chicana feminism influence your work?

Chicana feminism saved my life. I often share an anecdote in my feminist consciousness journey about how I came upon Chicana feminist theorists in the stacks of Watson Library at the University of Kansas. I was researching for a Women’s Studies paper and stumbled upon the Chicana feminism section and found myself in the pages of Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, Cherríe Moraga’s Loving in the War Years, Emma Pérez’s The Decolonial Imaginary, and the wonderful anthology edited by Carla Trujillo, Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About. I sadly had not encountered their work in my classes as a women’s studies major at KU in the early 2000s, but when I found them on my own my world opened up. So, in this sense, Chicana feminism is the foundation for all my work. I am a Chicanx feminist, which means I am committed to the struggle to uplift, empower Chicanas and genderqueer Chicanx folks in this world that often minimizes or erases our contributions. I’m particularly committed to uplifting our communities in what others feel are unlikely places, like the prairies of Kansas or where I currently reside, West Central Minnesota.

A critical component of Bold Women is that it highlights genealogies of feminist art. Are there feminist artists who have influenced your practice, and if so, how?

Absolutely! As an interdisciplinary feminist scholar, writer, and visual artist I count anyone who works creatively or anyone who turns ideas into something material (like thoughts into a book) as inspiration. All the amazing feminist scholars I mentioned previously definitely influence my art practice, especially as I find ways to integrate their teachings into the visual realm. As for my feminist visual artist influences, I point to Amalia Mesa-Bains, who in addition to being a curator, writer, and overall chingona [Spanish slang for "a bad-ass woman"] also creates these gorgeous installations that inspire us to think about memory, home, and belonging. She is an artist who does all the things I wish to do with my art in terms of intervening in systems like museums with Chicana feminist perspectives. In particular, her work Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache helps me thematically focus on the space of the home as central to my work, and unapologetically integrate and repurpose materials beyond their original use with a feminist rasquache ethic. [Amalia Mesa-Bains defines rasquache" as an art movement and cultural sensibility characterized by irreverent uses of everyday, inexpensive materials.]

In my use of textiles, and in particular quilting, I see my quilted paintings as a direct influence of the work of Faith Ringgold and her story quilts. While I am using a different approach to my narrative paintings and integrating quilted elements, my work follows on the path she carved in encouraging quilting as a medium worthy of fine art attention.

And lastly, I am in the lineage of all feminist artists who came before me, who boldly and unapologetically stated they were feminists and artists, who used their voices to critique and challenge the status quo and set the stage for us to continue to achieve gender parity in museum collections and the art world more broadly.

Santa Fe, Kandace Creel Falcón

Feminism, queerness, space, and rural communities are consistent themes within your work. What are the connections among these topics, and have they changed over time?

While I was born in the Flint Hills of Kansas (Manhattan), I moved with my family to New Mexico when I was two and grew up in an urban, desert environment. However, I grew up always loving to visit my Tía’s rural home which is about a 25-minute drive outside of Emporia, Kansas. I felt such freedom and connection with the prairie, and all the animal critters who lived there. I dreamt of living in a rural place for a long time, and when my wife and I bought a home in rural Otter Tail County, Minnesota, in 2017, we made that dream come true. There is a level of freedom in living in a rural place that is difficult to describe for folks who have not experienced it. It is a freedom to be yourself fully within the safety of one’s property, and I find I am more in sync with nature at this point in my life because of my rural location than ever before.

I have frequently thought about space in my work because one of my favorite themes to explore in my paintings is interiority. But, of course, the inside cannot be understood without the outside. And it’s made me think about the possibilities for the site of the canvas to hold multiple truths and share wisdoms from many temporalities and spaces all at the same time. The painting becomes a third space between idea and material in that it captures process in a very particular way. In my estimation, this is a very queer and feminist approach, or an ethic that shapes how I’m inviting others to see the world around them, beyond the status quo, social norms, or expectations. That painting invites this possibility through the process, for me, is a real gift that brings me back to the medium time and time again. I’m grateful that this knowing and gift has deepened as I continue to paint.

Can you speak about your transition from academia to becoming an artist? Did this shift how you think about feminist knowledge production and storytelling?

I left academia in the spring of 2019 as a tenured associate professor and director of women’s and gender studies at a regional public university in Minnesota. That decision was not made lightly as my scholarly path was all I had known up until that leap. After I left, I went back to school to get an associate of fine arts degree in visual arts and graduated virtually during a lockdown period in 2020. As I fell more and more in love with painting and visual art in school and following graduation, I immediately connected to how gaining skills in the visual realm expanded my personal toolkit for feminist knowledge production. When I started my visual art educational journey, I knew I wanted to tell stories in new ways, beyond words alone. As I have continued to paint and develop my style over the last few years, I am grateful for my paintings to be portals for intersectional feminist education and teaching possibilities on their own and in combination with my writing and thinking that becomes all part of my art practice.

What are you working on now?

I am currently working on a series of quilted paintings about my childhood bedrooms. It is a new technique and challenge for me to find ways of integrating fabric and quilting techniques into the same space of a painted field. The paintings are about my past childhood experiences and integrate nature and information from the oral histories I’ve conducted with my parents. But most importantly, these paintings are about quilting myself together as I look back on the last 40 years of my life and look ahead into the hopeful next four decades and beyond. I am childless by choice and am recycling and repurposing clothes I used to wear as a child, that were made for me by my Tía who I would visit on her rural farm, so it is really a full circle moment. Part reclamation, though very personal, I’m looking to see what feminist knowledge production can emerge from this space for me in this time through these interior portals.