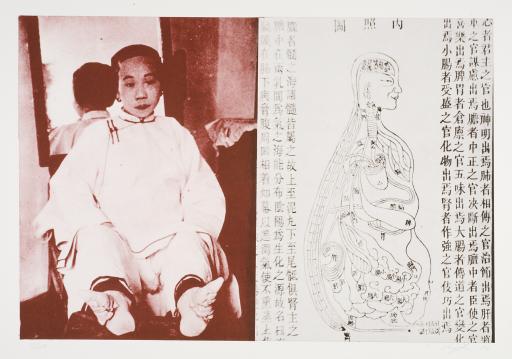

Bound Foot, Liu Hung

Artwork Overview

Liu Hung, artist

1948–2021

Bound Foot,

1992

Where object was made: United States

Material/technique: photolithograph

Dimensions:

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 422 x 617 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 573 x 762 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 16 5/8 x 24 5/16 in

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 22 9/16 x 30 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 24 x 32 in

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 422 x 617 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 573 x 762 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 16 5/8 x 24 5/16 in

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 22 9/16 x 30 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 24 x 32 in

Credit line: Museum purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Memorial Art Fund

Accession number: 1993.0301

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request