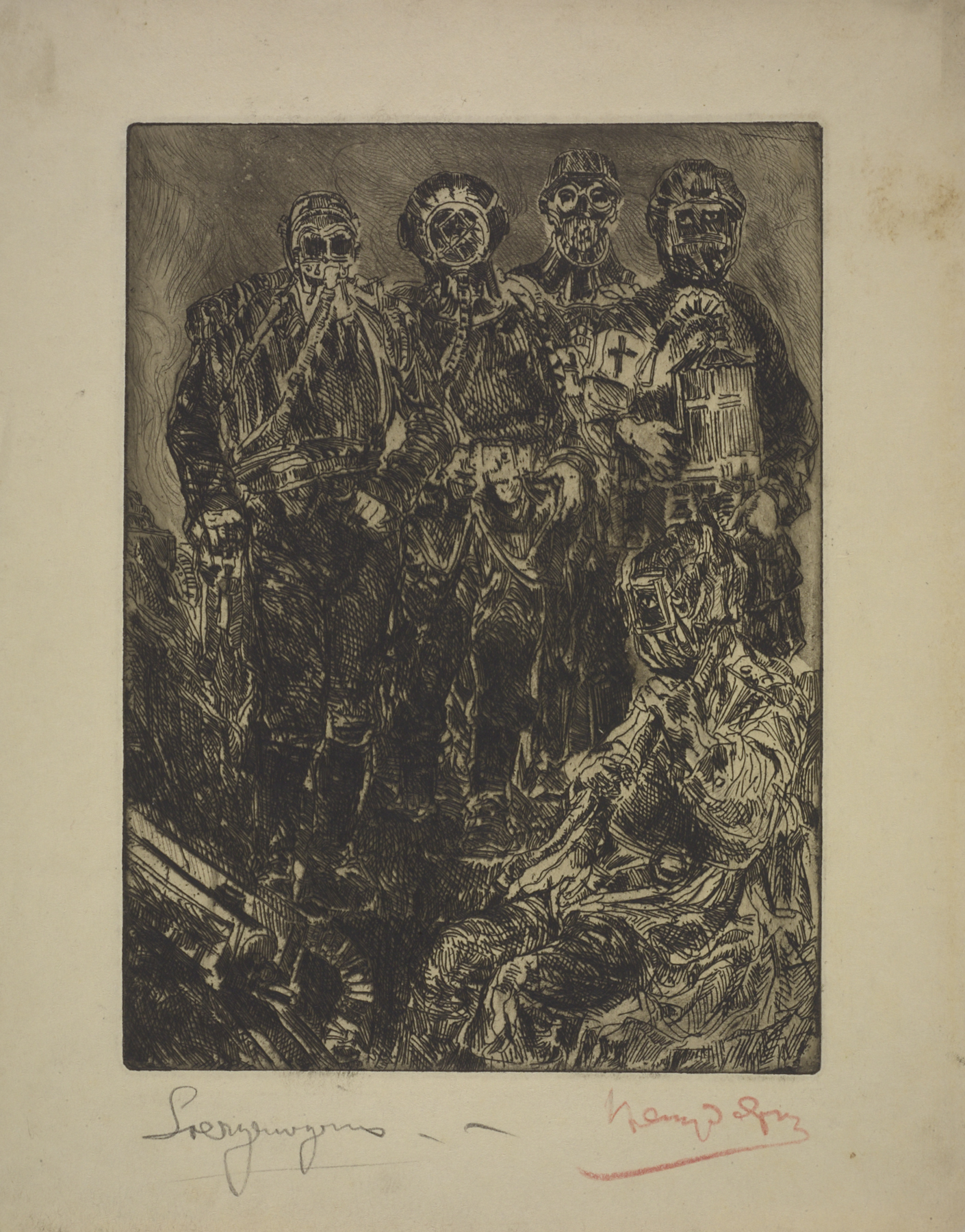

Lacrymogène (Teargas), Henry de Groux

Artwork Overview

Henry de Groux, artist

1867–1930

Lacrymogène (Teargas),

1915

Portfolio/Series title: Le Visage de la Victoire

Where object was made: Paris, France

Material/technique: aquatint; vellum; etching

Dimensions:

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 247 x 181 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 9 3/4 x 7 1/8 in

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 327 x 256 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 12 7/8 x 10 1/16 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 19 x 14 in

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 247 x 181 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 9 3/4 x 7 1/8 in

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 327 x 256 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 12 7/8 x 10 1/16 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 19 x 14 in

Credit line: Museum purchase: Helen Foresman Spencer Art Acquisition Fund

Accession number: 2005.0118

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request