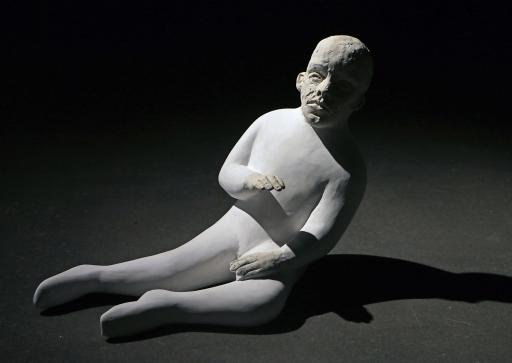

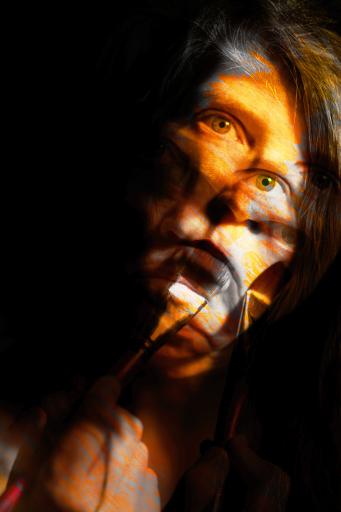

Student Juried Show: Restoring & Redefining the Body

Exhibition Overview

The 2021 virtual Student Juried Art Show considers how we undergo restoration after mental and physical hardship, and how these experiences can help us redefine our perceptions of the body and mind. How are we connected through our physical experiences? How do these experiences, individual and universal, shape our conceptions of the body, ourselves, and the world? The show’s theme expands on the ideas in the Spencer Museum’s exhibition Healing, Knowing and Seeing the Body.

Students at the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University were invited to submit works of art that explore the theme Restoring and Redefining the Body. The works featured in this show were selected by a committee of students on the Spencer Student Advisory Board with input from Curator Cassandra Mesick Braun.