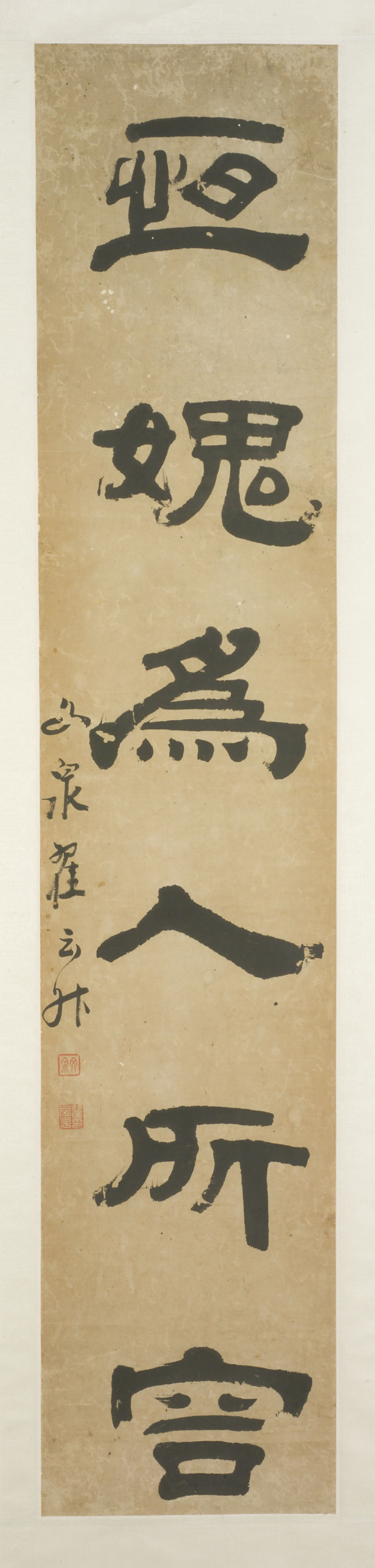

From the Way of Writing to the Weight of Writing

Exhibition Overview

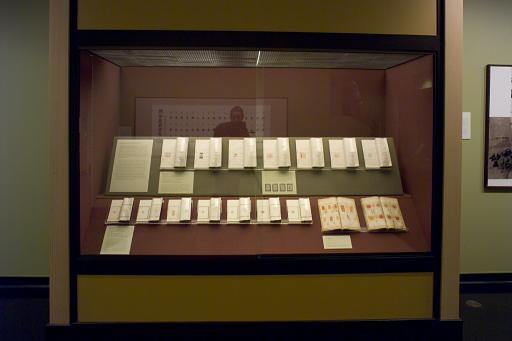

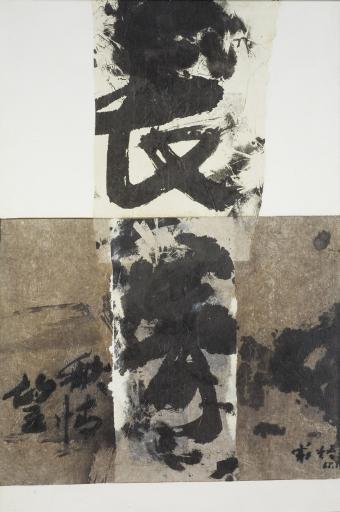

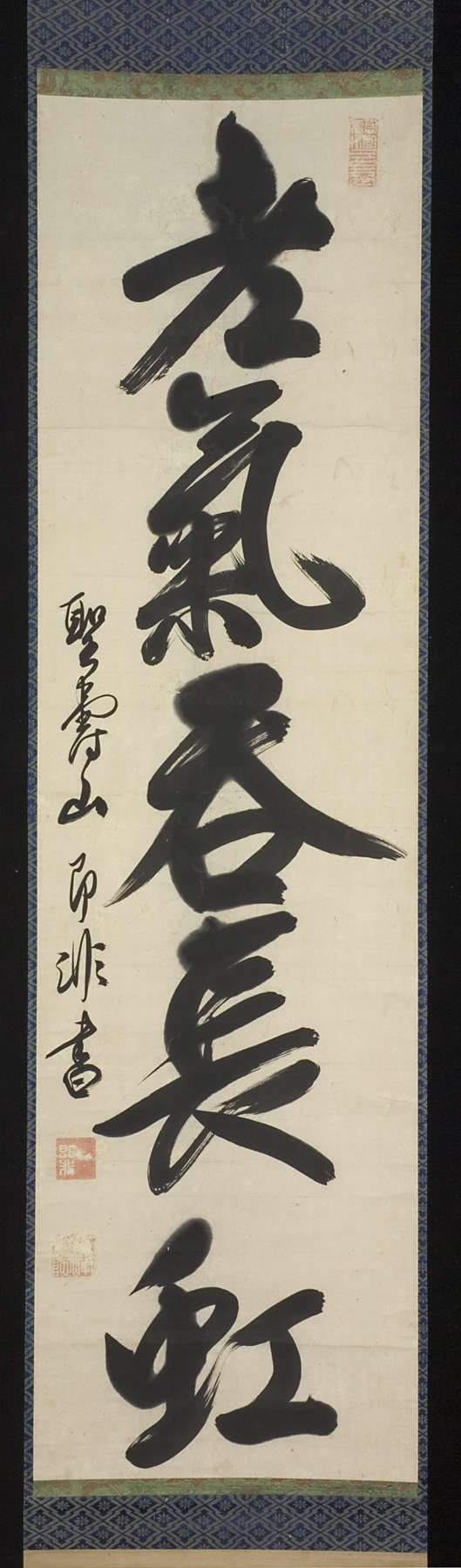

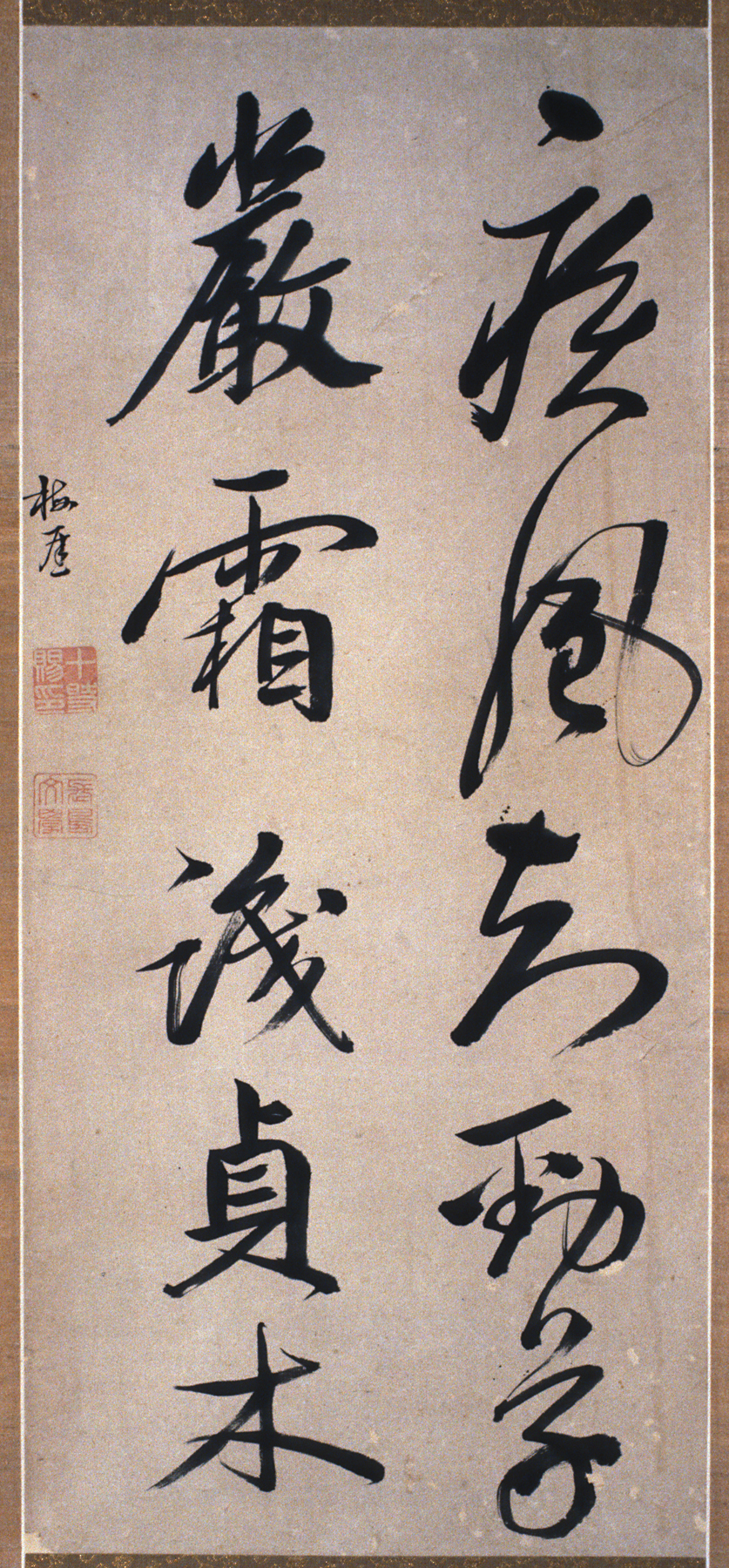

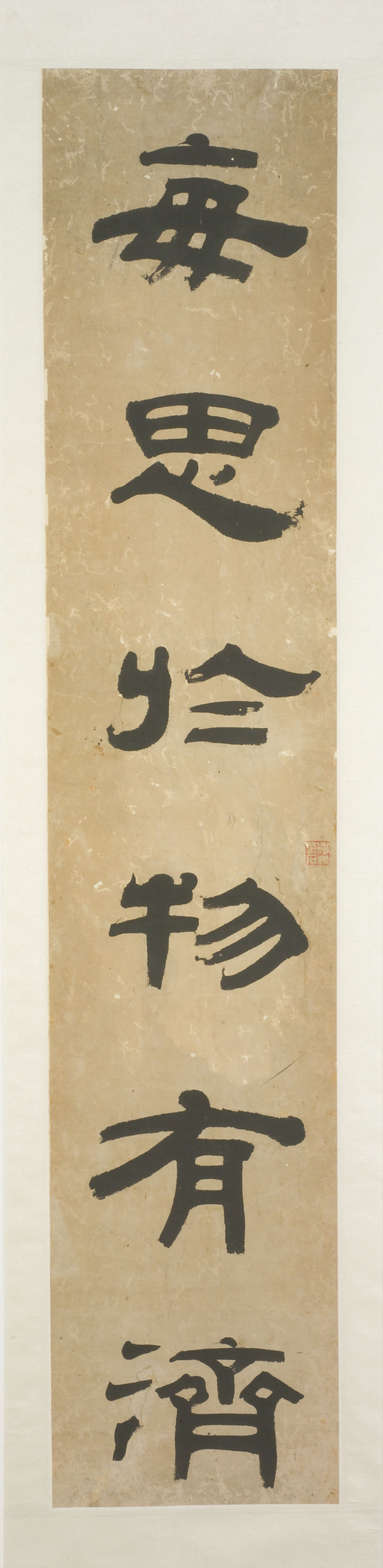

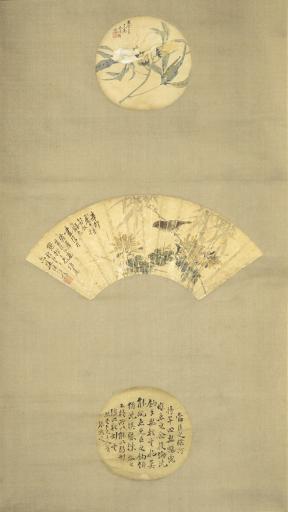

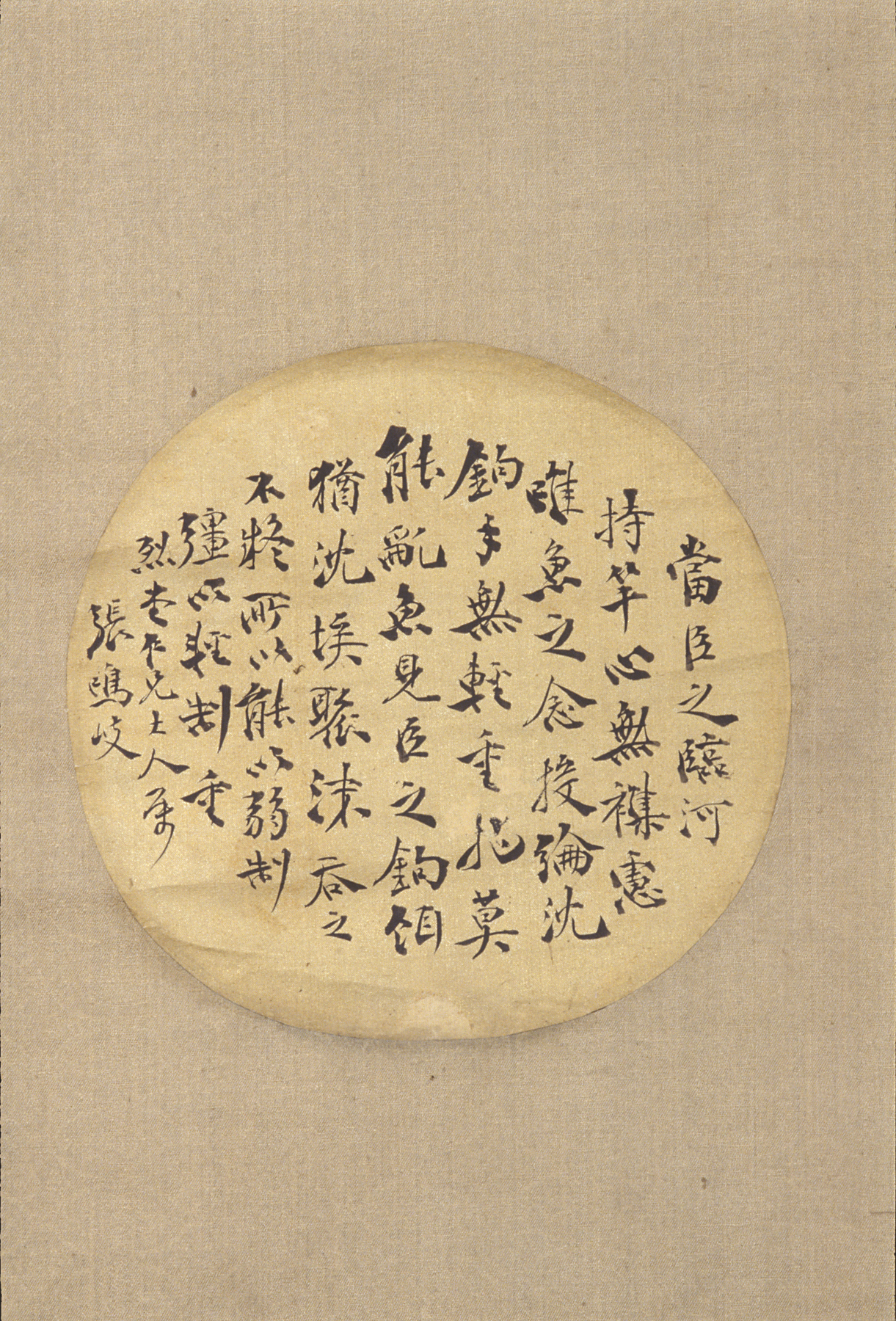

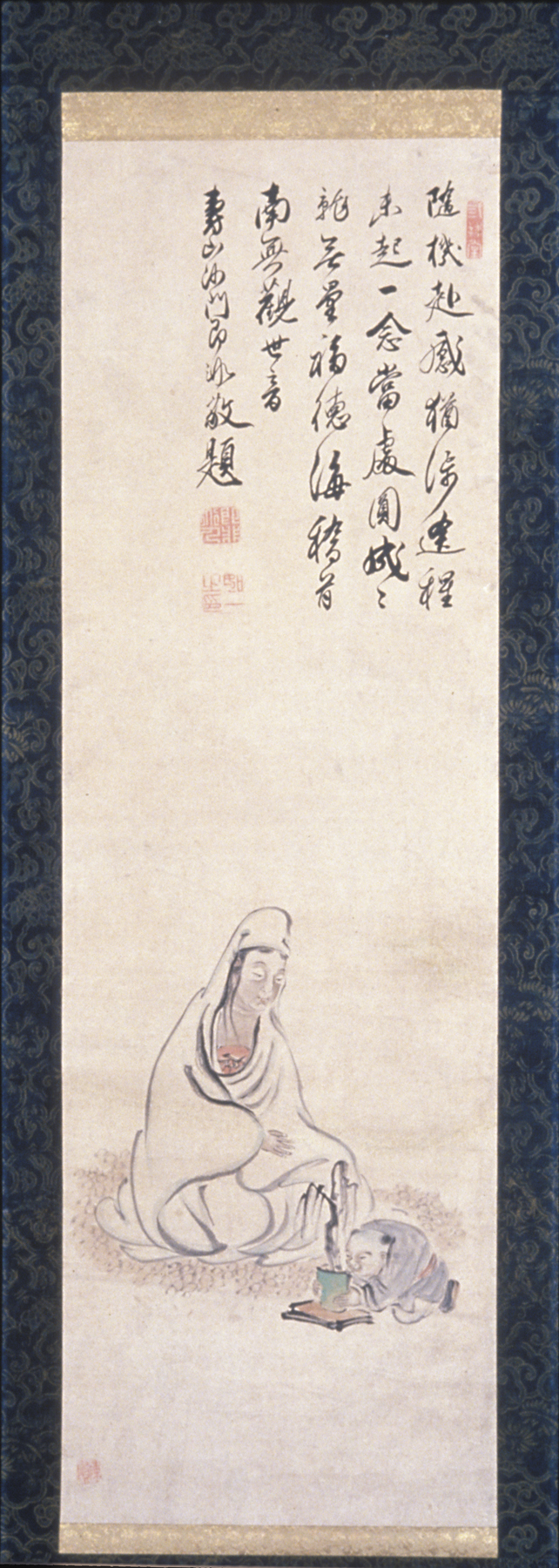

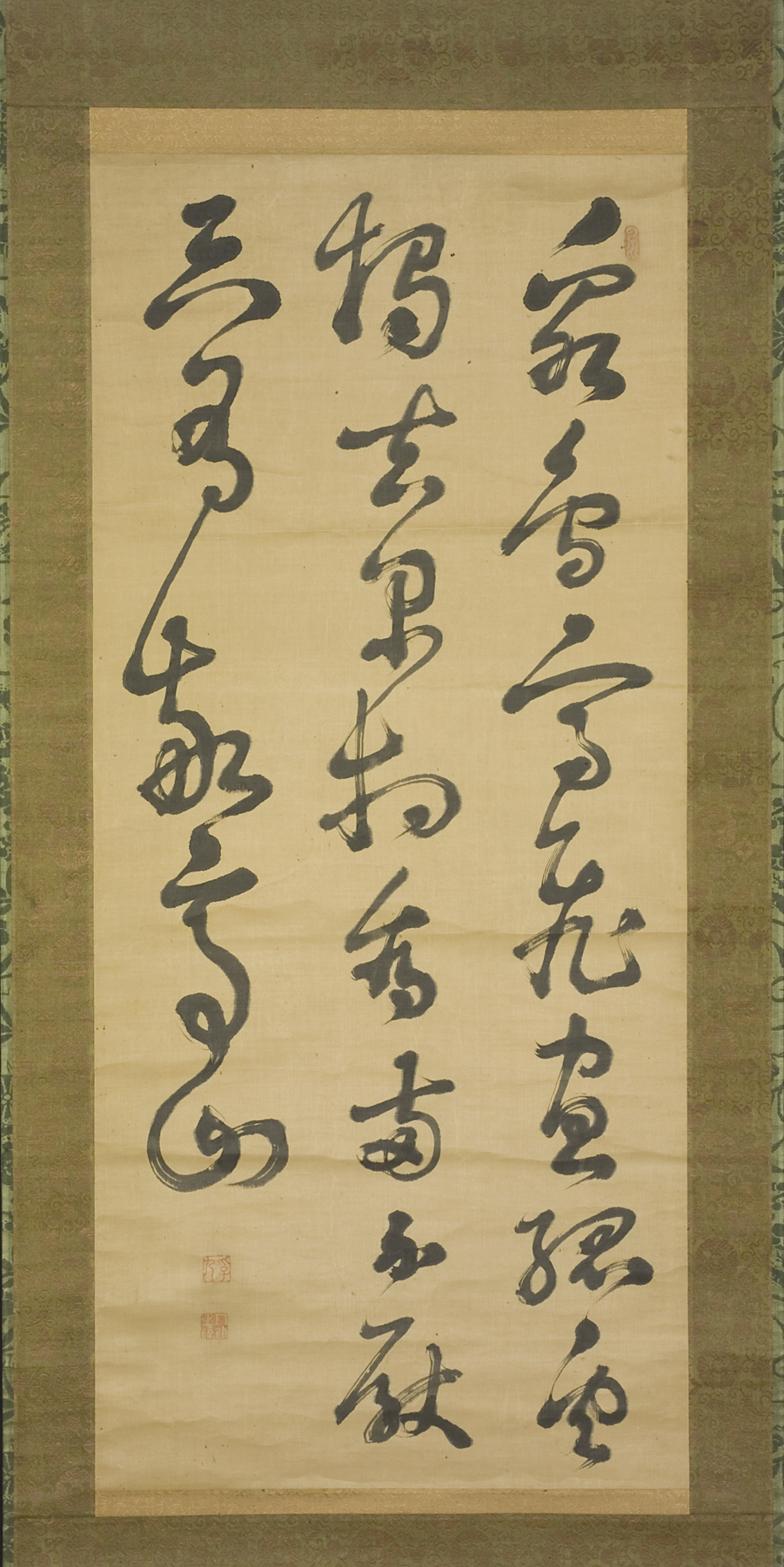

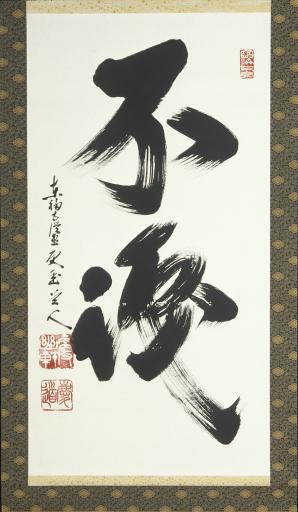

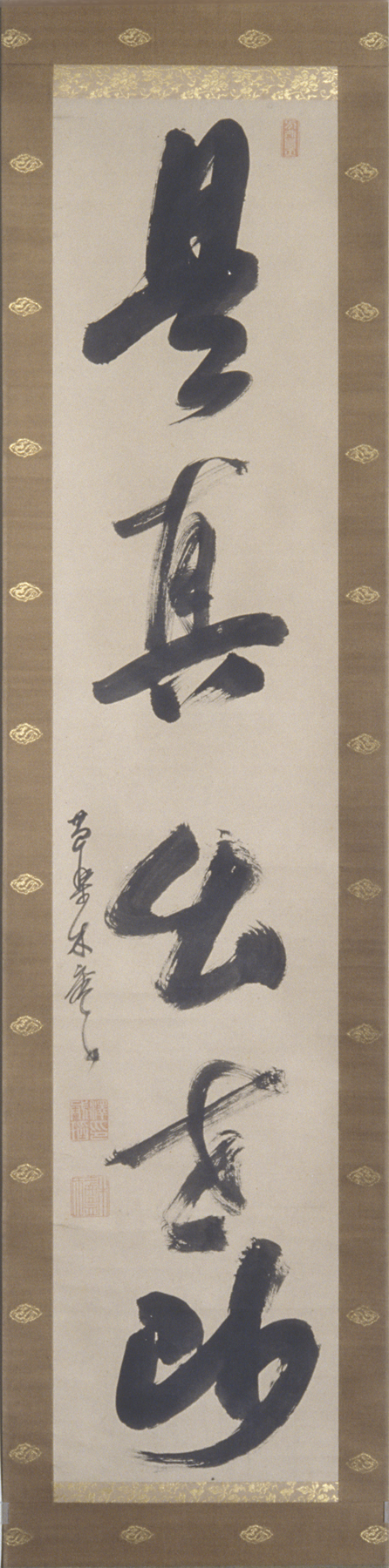

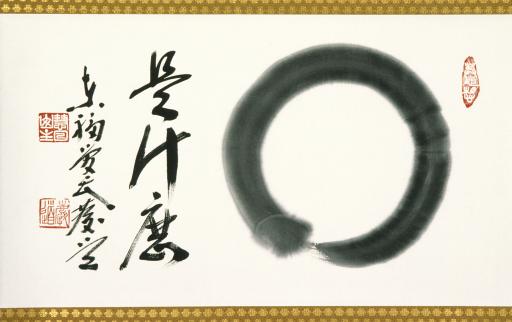

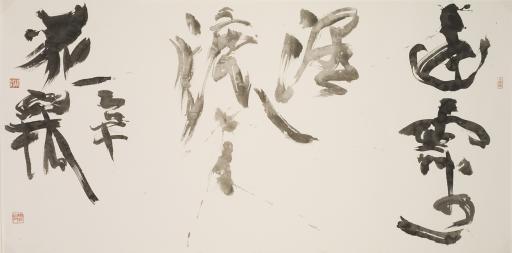

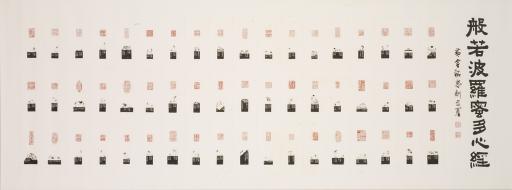

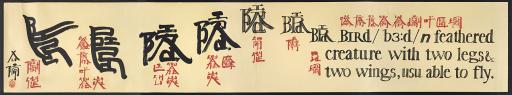

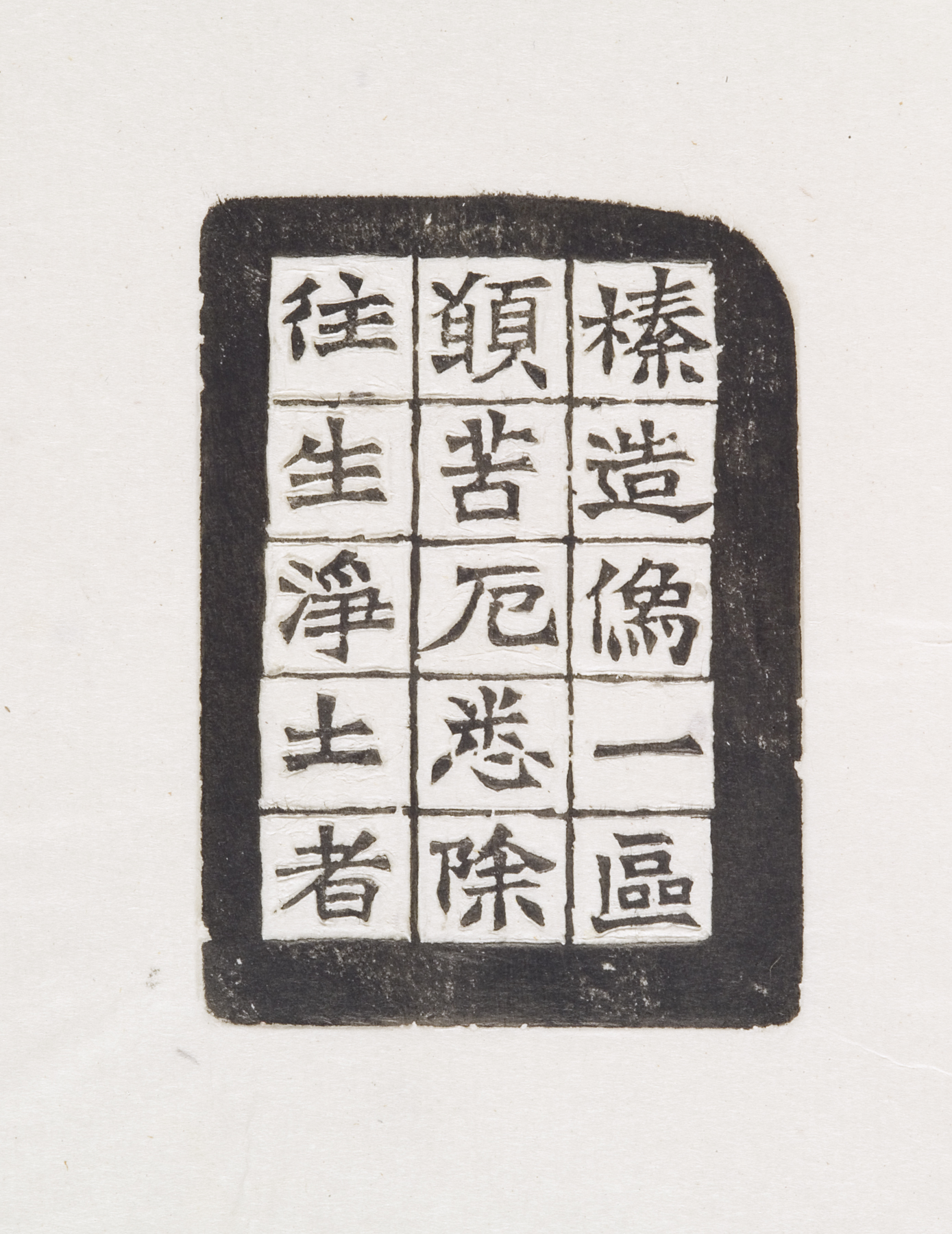

In East Asian languages, the word for “calligraphy” literally means “way of writing.” Calligraphy in Chinese culture is more than just beautiful writing; to the literary elites, calligraphy is not only a form of self-expression, it also embodies a person’s moral integrity. Even for the general populace, written words serve as emblems of learning and enlightenment, and therefore are objects of reverence. The calligraphic objects in the exhibition span many centuries and include works by contemporary artists. This display of calligraphy is intended to provide impetus for exploring the cultural weight of Chinese writing in East Asian societies. Beginning with calligraphic works on paper - the most direct form of writing as art, coming from the hands of the artists - the exhibition also aims to introduce several lesser known formats, including seal carving, book printing, Buddhist texts and ink rubbings. Furthermore, works by contemporary artists are included to attest to the vitality and relevance of calligraphy in the current art scene.