The Conqueror Worm, Claude Buck

Artwork Overview

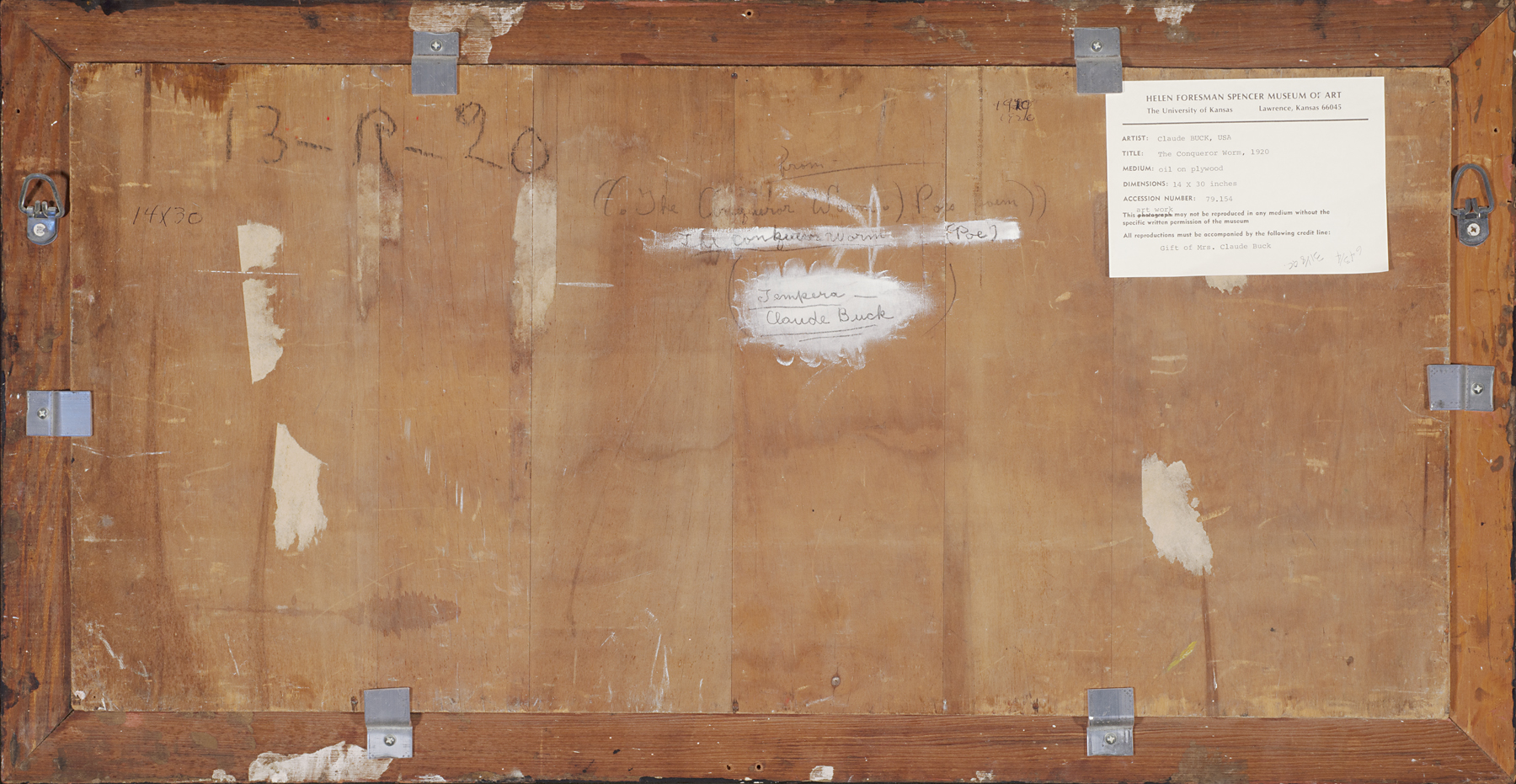

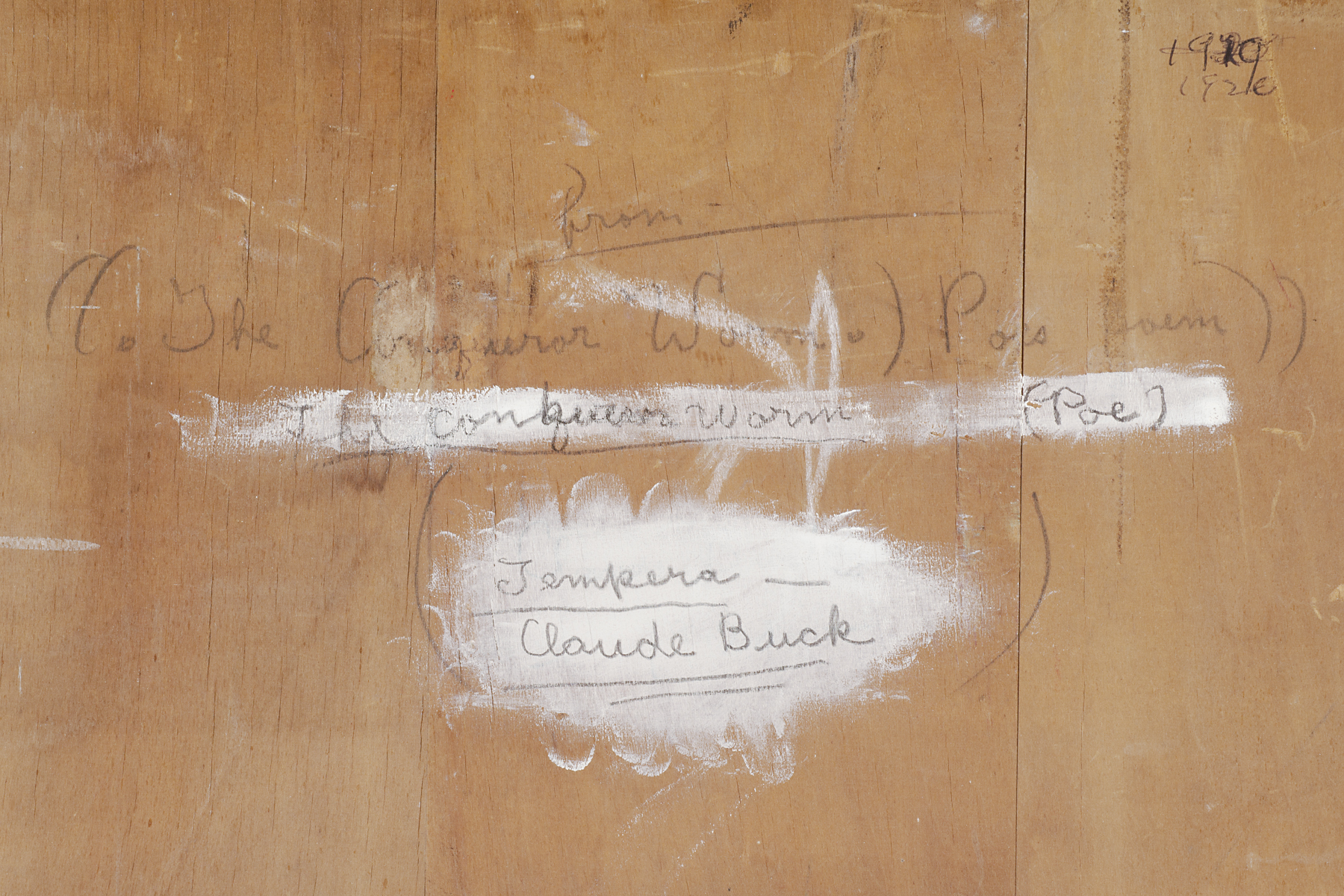

Canvas/Support (Height x Width x Depth): 35.6 x 76.2 cm

Canvas/Support (Height x Width x Depth): 14 x 30 in

Frame Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 17 1/4 x 33 x 1 1/4 in

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request

Images

Label texts

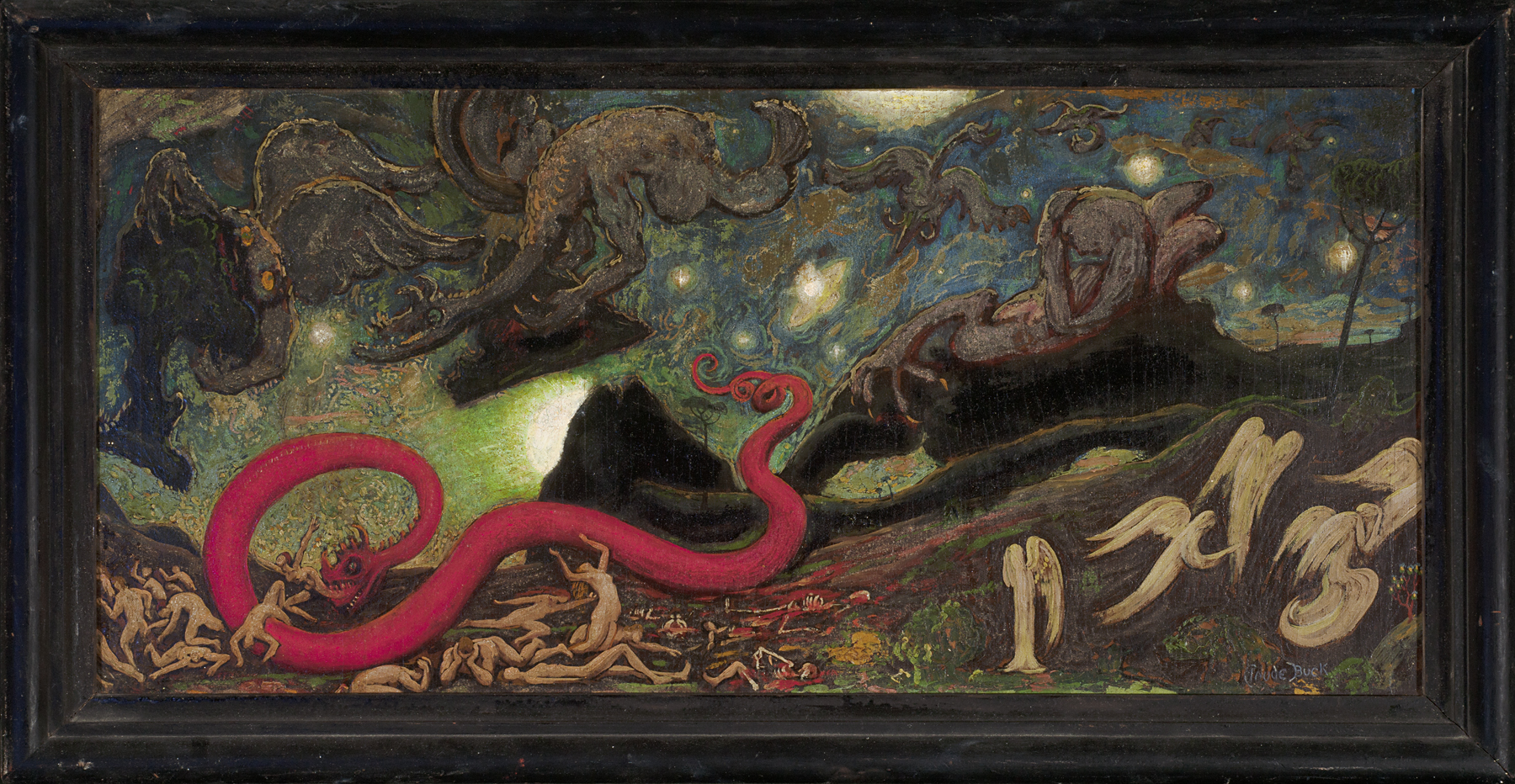

A gigantic red worm with glowing eyes slithers across a gloomy landscape, devouring naked bodies in its path. This surreal scene speaks to horrific visions of hell and the afterlife that often haunt the subconscious realm. As a leading advocate of symbolist art in Chicago, Claude Buck was known for his fantastic, sometimes disturbing images infused with allegorical and literary themes drawn from sources like the macabre writings of Edgar Allan Poe.

A gigantic red worm with glowing eyes slithers across a gloomy landscape devouring naked bodies in its path. This surreal scene speaks to horrific visions of hell and the afterlife that often haunt the subconscious realm. As a leading advocate of symbolist art in Chicago, Claude Buck is known for his fantastic, sometimes disturbing images infused with allegorical and literary themes drawn from sources like the macabre writings of Edgar Allan Poe.

Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Conqueror Worm” (1843) has had a long half-life, beginning with its incorporation into Poe’s own story “Ligeia” two years later. In Poe’s morbid verse, a group of angels, “mimes in the form of God,” attend a play with Madness, Sin, and Horror central to the plot. Into the drama writhes a blood-red thing that devours the angels as a funeral pall descends, thereby concluding the tragedy whose only hero is The Conqueror Worm. Over the decades the poem has prompted various responses, from musicians in particular, from composer Franz Bornschein’s choral work (1935) to Lou Reed’s version (2003) to a verbatim recording by Goth musician Aurelio Voltaire (2014). Comic books spread the poem’s sentiments to other new audiences, as do puppets performing in an Australian music video.

In 1920, Claude Buck unveiled his interpretation of the poem, the culmination of the painter’s long-time fascination with Poe. When first shown, one critic praised Buck’s interpretations of Poe, among which, “The Conqueror Worm rather dominates [the exhibition].” Another noted that Buck’s paintings, “commanded attention wherever they were shown,” even though his “ultra-mystic” art was “not acceptable to the average picture buyer.” Decades later,

opinion was still divided about Buck’s paintings as suggested by an evaluation in 1983: “[Buck] produced some of the most thoroughly wacko paintings of their day,” the reviewer wrote, while also praising the “apocalyptic version of The Conqueror Worm . . . [which] remains his most memorable work.”

I’ve always enjoyed wacko—but there’s no accounting for taste. My esteemed colleague and friend for more than 40 years, the late Marilyn Stokstad, teased me about this acquisition, predicting that I’d always be known as “the guy who brought The Worm to campus.” I’m happy to be, and so I include it here in memory of her. CCE

Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Conqueror Worm” (1843) has had a

long half-life, beginning with its incorporation into Poe’s own story

“Ligeia” two years later. In Poe’s morbid verse, a group of angels, “mimes in the form of God,” attend a play with Madness, Sin, and Horror central to the plot. Into the drama writhes a blood-red

thing that devours the angels as a funeral pall descends, thereby

concluding the tragedy whose only hero is The Conqueror Worm. Over the decades the poem has prompted various responses, from musicians in particular, from composer Franz Bornschein’s choral work (1935) to Lou Reed’s version (2003) to a verbatim

recording by Goth musician Aurelio Voltaire (2014). Comic books spread the poem’s sentiments to other new audiences, as do puppets performing in an Australian music video.

In 1920, Claude Buck unveiled his interpretation of the poem, the

culmination of the painter’s long-time fascination with Poe. When first shown, one critic praised Buck’s interpretations of Poe, among which, “The Conqueror Worm rather dominates [the exhibition].”

Another noted that Buck’s paintings, “commanded attention wherever they were shown,” even though his “ultra-mystic” art was “not acceptable to the average picture buyer.” Decades later,

opinion was still divided about Buck’s paintings as suggested by an evaluation in 1983: “[Buck] produced some of the most thoroughly wacko paintings of their day,” the reviewer wrote, while also praising the “apocalyptic version of The Conqueror Worm . . . [which] remains his most memorable work.”

I’ve always enjoyed wacko—but there’s no accounting for taste. My esteemed colleague and friend for more than 40 years, the late Marilyn Stokstad, teased me about this acquisition, predicting that I’d always be known as “the guy who brought The Worm to campus.” I’m happy to be, and so I include it here in memory of

her. CCE

A gigantic red worm with glowing eyes slithers across a gloomy landscape devouring naked bodies in its path. Perhaps a remnant from a dream by the artist, the surreal scene speaks to horrific visions of hell and the afterlife that often haunt the subconscious realm.

Exhibition Label:

"Corpus," Apr-2012, Kris Ercums

A gigantic red worm with glowing eyes slithers across a gloomy landscape devouring naked bodies in its path. Perhaps a remnant from a dream by the artist, the surreal scene speaks to horrific visions of hell and the afterlife that often haunt the subconscious realm.

Exhibition Label:

"Dreams and Portals," Jun-2008, Kris Ercums and Susan Earle

A leading member of the avant-garde symbolist artists in Chicago, Claude Buck is known for his fantastic, sometimes disturbing images with allegorical and literary themes drawn from sources including the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, the operas of Richard Wagner, classical mythology, and New Testament writings from the Bible. In the 1920s to earn money by gaining public favor and also expressing his increasing disdain for modernism, Buck did a number of “hyper-real” portraits, figures and still lifes. These proved popular and aligned him with the opponents of abstraction and their “Sanity in Art” movement, whose headquarters were in Chicago.