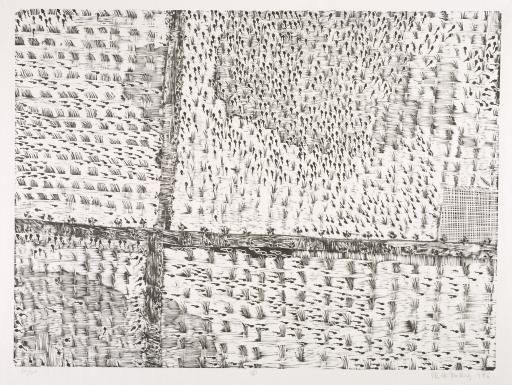

Rice field, Xu Bing

Artwork Overview

Xu Bing, artist

born 1955

Rice field,

1986

Portfolio/Series title: The Pastoral Woodcut Series

Where object was made: Beijing, China

Material/technique: woodcut

Dimensions:

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 545 x 740 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 21 7/16 x 29 1/8 in

Plate Mark/Block Dimensions (Height x Width): 545 x 740 mm

Plate Mark/Block Dimensions (Height x Width): 21 7/16 x 29 1/8 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 29 x 37 in

Frame Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 29 1/4 x 38 1/4 x 1 in

Weight (Weight): 10 lbs

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 545 x 740 mm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 21 7/16 x 29 1/8 in

Plate Mark/Block Dimensions (Height x Width): 545 x 740 mm

Plate Mark/Block Dimensions (Height x Width): 21 7/16 x 29 1/8 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 29 x 37 in

Frame Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 29 1/4 x 38 1/4 x 1 in

Weight (Weight): 10 lbs

Credit line: Museum purchase: Lucy Shaw Schultz Fund

Accession number: 2005.0071

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request