The scientific study of human anatomy began as early as 1600 BCE, when Egyptians compiled the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, a written text demonstrating knowledge of several organs and bodily systems and named after the dealer who bought the text in 1862. However, many world religions prohibited dissecting or portraying the human form, slowing the development of a visual language for depicting its anatomy for centuries. The works in this section trace this history through important anatomical illustrations—from a 14th-century Persian manuscript to the revolutionary work of Andreas Vesalius in the 1500s; from the earliest recordings of the human pulse as a waveform to photographic documentation of HIV-positive bodies in the 1980s.

All of these reflect the capacity of anatomical illustration—and the medical gaze more broadly—to simultaneously distance and connect, anonymize and personalize. The representation of the human body in medical contexts raises many interrelated questions: How have techniques for seeing the body changed through time, and how have they influenced our understandings of the human body? Can art play a more significant role in our understandings of the body beyond illustration?

How can depictions of bodies connect through time and across space?

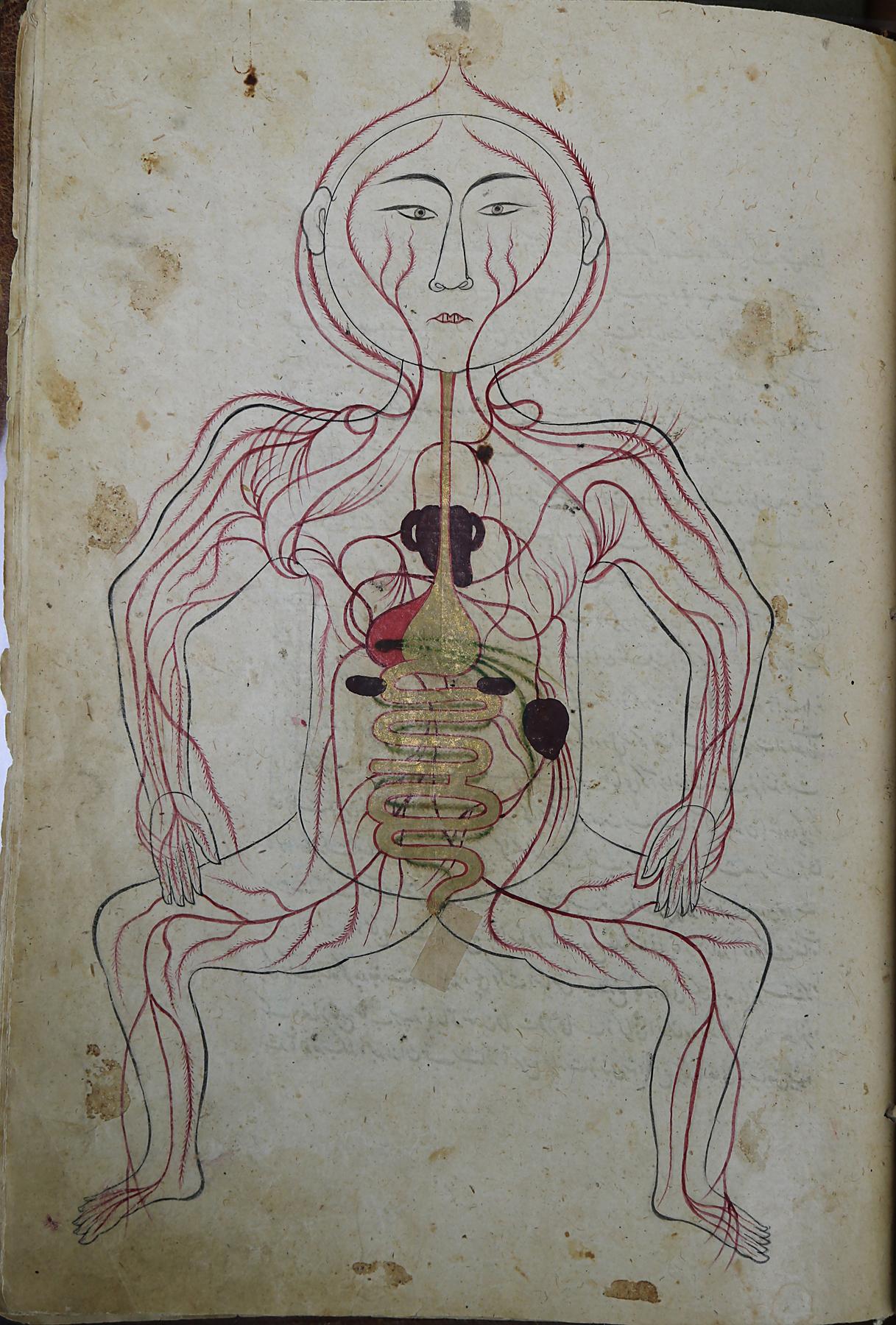

Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān (Mansur’s Anatomy), Manṣūr ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf Ibn Ilyās

Tashrih text

The Persian scholar, physician, and anatomist Manṣūr ibn Ilyās is widely credited with creating the first color atlas of the human body in the early 1400s. Organized into five chapters, the manuscript explores, through illustration and extensive notation, the skeleton, nervous system, muscles, veins, and arteries, with a final section depicting a pregnant woman. Mansur’s Anatomy was used in other Persian and Arabic medical treatises for more than 200 years. Much of the scholarship on early anatomists overlooks those working in the Medieval Islamic world, largely due to the still-debated assumption that religious beliefs prohibited the dissection of human bodies. Regardless of whether it evinces human dissection, Mansur’s Anatomy was still significant in that the use of color was previously considered to be against Islamic law.

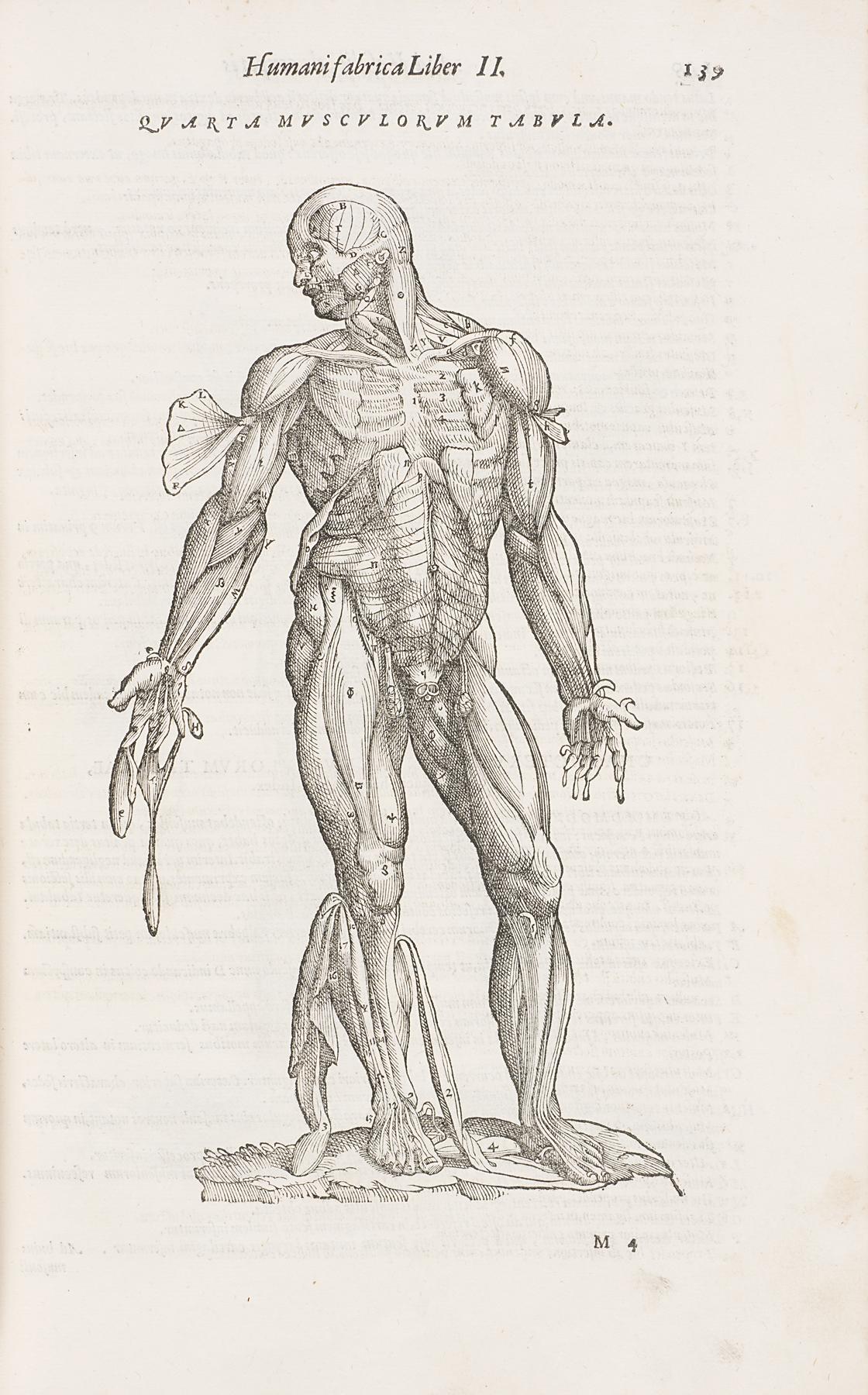

De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), Franciscus Francisci and Johannes Criegher; Andreas Vesalius

Vesalius text

The Flemish doctor and surgeon Andreas Vesalius has been heralded as the founder of modern anatomy. His 1543 publication De humani corporis fabrica, shown here in a 1568 reprint, was the first Western anatomical treatise to be based on close observation of the human body through dissection. Vesalius made dozens of discoveries as a result of his thoughtful research and disproved prevailing ideas about the body—primarily those espoused by the second-century Greek physician and philosopher Galen—that were not based on direct observation. Vesalius’s “muscle men” from a chapter on the muscular system are among the most iconic of all anatomical illustrations.

Vesalius’s work has continued to influence artists and scholars today. Sean Caulfield’s Virus prints and The Anatomy Table, both on view in Healing, Knowing, Seeing the Body, adopt imagery straight from Vesalius’s illustrations.

Caricature of the Laocoön represented as a Monkey in a Landscape, Nicoló Boldrini; Titian

Laocoon label

In 1545, Venetian artist Titian satirized a Hellenistic sculpture of Laocoön, a character from Greco-Roman myth, by showing Laocoön not as an idealized, muscular human but rather as a monkey. Titian’s odd drawing, transformed into a woodcut by Boldrini, has been interpreted as a subversive critique of the dominant understanding of the human body at the time, which was informed by the second-century teachings of the Greek physician, writer, and philosopher Galen. Galen and his followers based their understanding of human anatomy based solely on animal dissection, particularly the Barbary ape. In the mid 1500s, Andreas Vesalius began widely criticizing Galen’s ideas based on his direct observation of anatomy through comparative dissections of human cadavers.

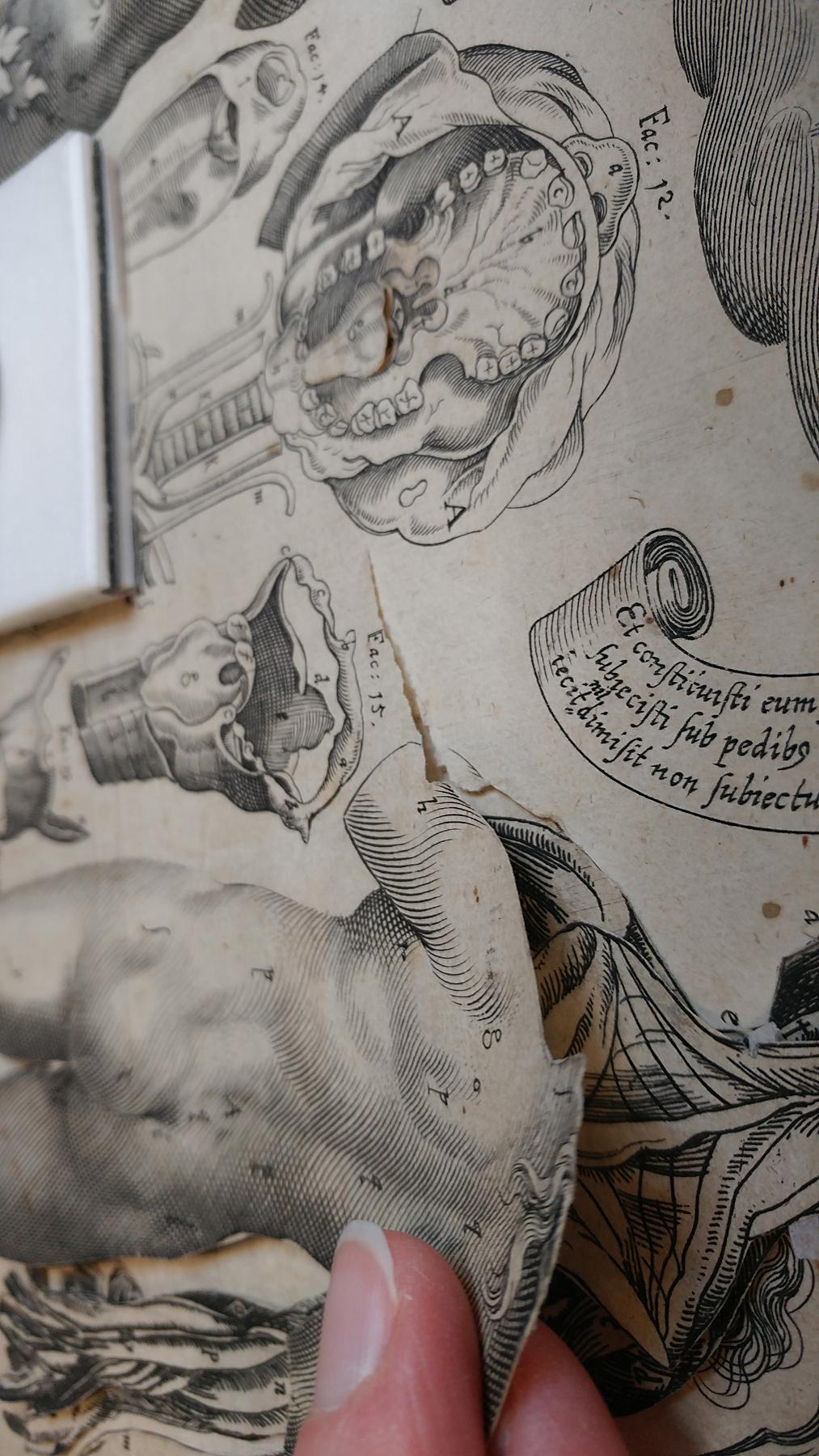

Anatomical Plate with Male and Female Figures, Lucas Kilian; Johann Remmelin; Stephan Michelspacher

Killian text

Lucas Killian’s anatomical flap book is meant to educate through active manipulation rather than passive study. This “visible man” and “visible woman” have layers that can be pulled back to reveal the organs and the circulatory, nervous, and skeletal systems of the figures. To make the illustrations even more interactive, some flap anatomies included “dissectible” hearts and lungs that allowed the handler to completely remove them in order to get a closer look at these vital organs. Beneath the last flap of this illustration, there is text in Latin from the Wisdom of Sirach, an ancient religious text exalting the skill of physicians and reminding readers that healing comes from God.

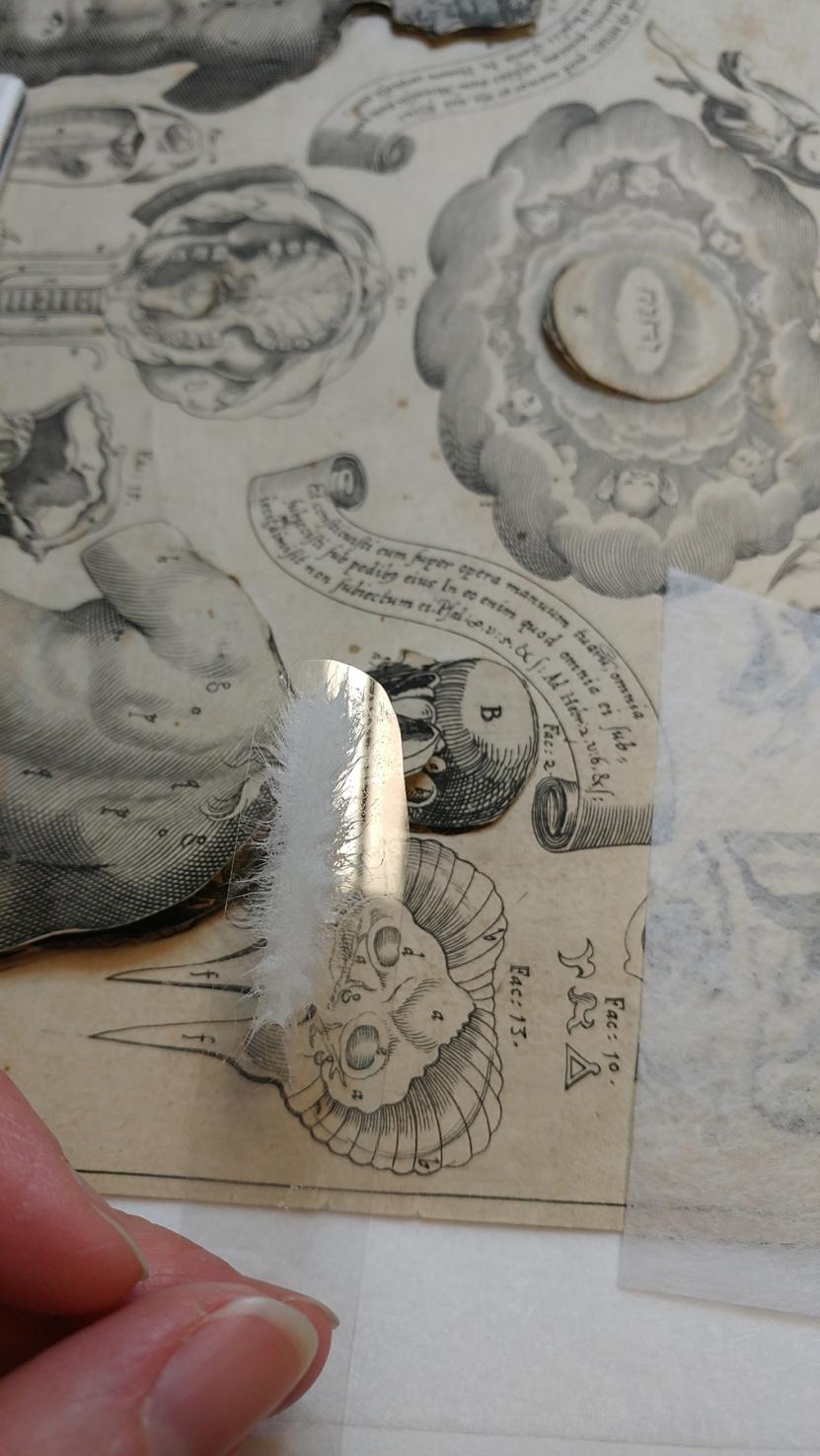

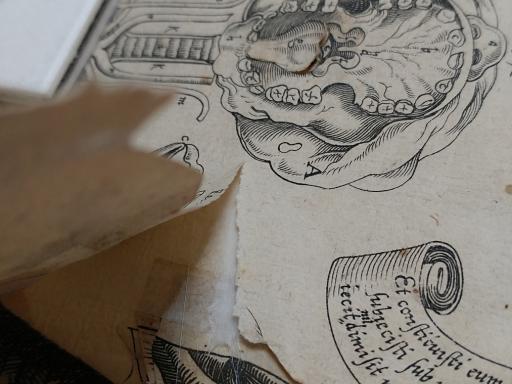

The Conservation Treatment of Lucas Kilian’s Interactive Print, "Anatomical Plate with Male and Female Figures"

This anatomical print, produced in 1613 by the German printmaker Lucas Kilian (1579–1637), is an example of a paper object that was meant to be touched. The outer edges of the male and female figures and other elements (ear, eye, etc.) are cut into paper flaps under which several additional paper layers are inserted and printed with images of the underlying layers of that portion of the body. The result is an educational tool that allows the user to explore various body systems.

As you might expect, years of handling these flaps created small tears, folds, and creases. Conservator Jacinta Johnson examined the print in preparation for the exhibition and developed a treatment plan to address these vulnerabilities. Handmade Korean paper (hanji) was selected to mend the tears due to its high-quality fiber content. The mends were pasted out with wheat starch paste and then placed on a long, polyester spatula cut to fit beneath the tear. This spatula was used to safely insert the mends between the layers that were then dried under light weight and blotter. Then the spatula was removed and the mend was complete. After all tears and creases were sufficiently reinforced with new paper mends, the print could be safely exhibited.

Conservation gallery

Tab. II The Fourth Order of Muscles, Back View, Jan Wandelaar; Bernhard Siegfried Albinus

Tab. III The Skeleton, Side View, Jan Wandelaar; Bernhard Siegfried Albinus

Tab. IV The Fourth Order of Muscles, Front View, Jan Wandelaar; Bernhard Siegfried Albinus

Tab. VIII The Skeleton, Back View, Jan Wandelaar; Bernhard Siegfried Albinus

Skelton text

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, a Dutch-German anatomist, has often been compared to his predecessor Andreas Vesalius: both were known for their accurate illustrations based on firsthand observations of human cadavers in various states of dissection. Albinus’s structuralist approach to understanding the human body began with the skeleton, onto which muscles were overlaid, followed by viscera, the circulatory system, and nerves. Although well-respected for the accuracy of his work and scientific methodology, Albinus also believed in the concept of homo perfectus, an idealized form of the human body. Working with artist Jan Wandelaar on the illustrations for his famous Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corpopris humani, Albinus imbued his anatomical models with this idealized and decidedly non-objective beauty characterized by symmetry and vitality.

Together, Wandelaar and Albinus also devised a new method of creating anatomical illustrations: A square-webbed net would be placed at regular intervals between the artist and the specimen so that the images could be copied using a grid, not unlike the techniques many muralists work to scale preparatory sketches to monumental proportions. Wandelaar’s artistry continued in the elaborate backgrounds he created for the cadavers, some even including Clara, an Indian rhinoceros who famously toured Europe between 1741 and her death in 1758.

Micrographia; or, Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses. With observations and inquiries thereupon, Robert Hooke

Hooke label

Robert Hooke has been referred to as an English Leonardo da Vinci in recognition of his extraordinary work as a scientist, natural philosopher, and architect. Micrographia represents Hooke’s pioneering work in microscopy, in which he became the first person to visualize a microorganism. His detailed illustration of a miniscule flea as seen under his microscope is among Hooke’s most famous contributions from this volume, but it also contains the illustration shown above, which accompanies the first known use of the word “cell” in a biological framework—an observation that would transform the Western understanding of the building blocks of life and set the stage for modern biology..

Hooke continues to influence artists and scientists today. Transdisciplinary artist Ingrid Bachmann, the International Artist-in-Residence for Healing, Knowing, Seeing the Body, created a series of sketches based on Hooke’s manuscript.

The Bonham Project Panel, Jon O'Neal

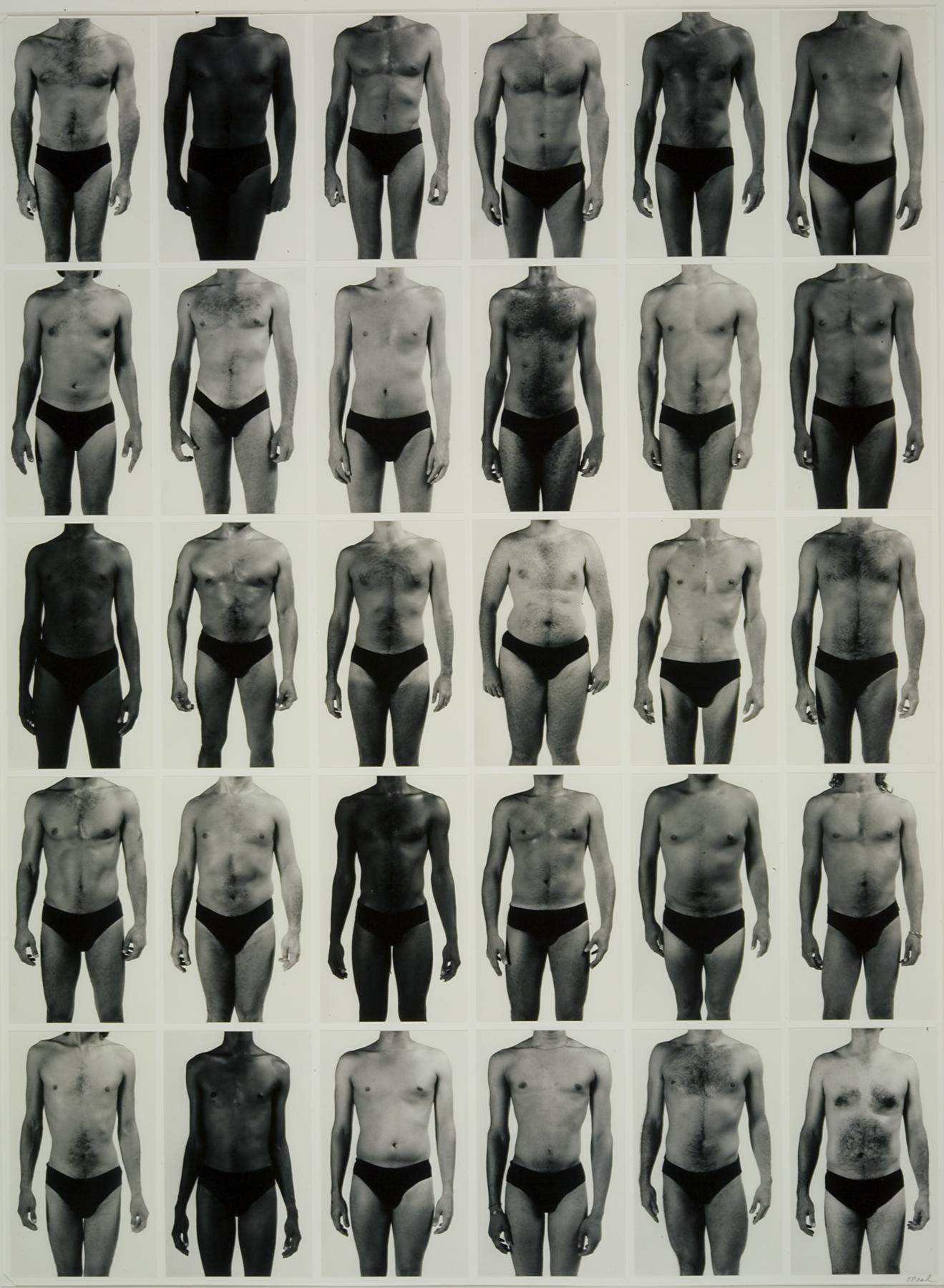

O'Neal label

As a physician and photographer, Dr. Jon O’Neal was tasked with studying the bodies of HIV-positive individuals as part of one of the U.S. military’s first systematic studies of AIDS. O’Neal became fascinated with understanding how a supposedly ill body—one infected with HIV—could show no obvious external signs of disease. His photographs were taken in a makeshift studio set up in The Bonham Exchange, a nightclub in 1980s San Antonio, Texas. O’Neal’s anonymized, disembodied images encourage us to consider how seeing bodies can at once feel intimate—even voyeuristic—and impersonal.

Healing, Knowing, Seeing the Body also includes works by Dr. Eric Avery, another physician and artist whose work addresses the 1980s AIDS epidemic.

Methuselah in Her Cradle, Dario Robleto

Dario label

Heartbeats are physical and real; they are also ephemeral and fleeting. Recording a heartbeat as a pulse wave freezes a moment in time—a moment in a life—but before and after that moment, the heart beats on, the body it belongs to inevitably aging. The late 19th-century French physician and homeopath Charles Ozanam was the first to consider the relationship between heartbeats and aging, recording pulses from the newest infants to those who lived for more than a century, in the process creating what Robleto calls a “comparative time map of the human heart.” The delicate wave forms memorialized here represent the heartbeats of infants to ten-year-old children in 1886.

The First Time, The Heart: A Portrait of Life, 1854–1913 | Installation by Huascar Medina

The prints in The First Time, The Heart: A Portrait of Life, 1854–1913 emerged from Dario Robleto’s research into the long quest to record the human heartbeat as a pulse wave. This visual translation of the heart’s activity has become an iconic part of our visual lexicon, whether as the wave itself (its undulations indicating life) or the flatline (its stillness a symbol of death). After the first pulse waves were recorded in 1853, scientists used them to visualize and study disease. Yet, in his research, Robleto also discovered examples that were not about disease at all; they instead recorded people undertaking everyday activities. To make this portfolio, he reproduced 50 of these outlier recordings, along with the scientists’ original notations, which Robleto describes as “at once documentation and poetry.”

To further highlight this beautiful and unexpected language, current Poet Laureate of Kansas Huascar Medina has resequenced the prints to create five different “portraits of life.” In looking at these pulse waves and the stories Medina tells, ask yourself: What do we owe to the memory of those who have come before us? How can the abstraction of the body into data distance us from the humanity and lived experiences of patients? How can we care for each other through time—and how can we care for each other during this particularly challenging time?

“How much can you ask from a simple line moving over time?”

Dario Robleto