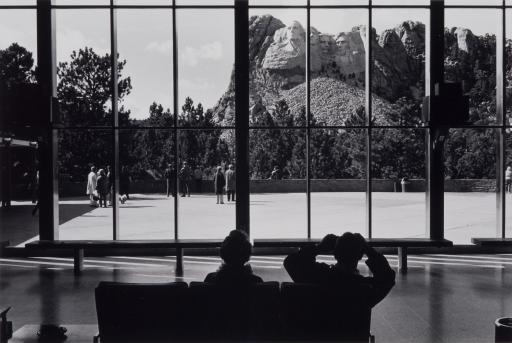

Conversation IV: Construction/Destruction

Exhibition Overview

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” John Keats (1795-1821)

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Art museums hold collections of constructed “things of beauty”-objects and groups of objects crafted and created by individuals or groups of individuals. Time and nature, however, have a secret. Once constructed, “things of beauty” begin an inevitable dance with destruction. Just how long can they last?

In response to John Keats, a museum worker will more likely note that a thing of beauty is a joy for a limited period of time depending on the medium of the object and its exposure to light and moisture. This practical assessment highlights a major challenge museums face: we care for objects that are inherently ephemeral. Art represents the cultural heritage of humanity and museums strive to safeguard that heritage. As we work to preserve our collections for future generations we must acknowledge that these objects will not last forever. Organic materials deteriorate rapidly, and objects can be damaged by pests, light, water, fire, or by accident. Ironically, when we place a delicate object on view in a gallery we incrementally hasten its eventual destruction. Museums battle this eventuality by attempting to preserve the lives of our objects for as long as possible.

There are many ways to perceive issues of preservation and conservation. Indigenous perspectives, for example, sometimes differ from Western museum practices. If an object is repatriated (returned to the descendants of its maker) indigenous caretakers may return it to use or bury it. Some indigenous peoples also believe certain objects that remain in museum collections should not be conserved or restored because the objects themselves are living entities and those treatments would interfere with their natural life cycle, which includes creation, or birth, and eventual death. Understanding and respecting indigenous perspectives is one way in which museums take responsibility for the stewardship of objects that represent living traditions. Moreover, it is important that museums continue to engage in the discourse surrounding the nature of cultural heritage objects and the issues related to the permanence and persistence of these “things of beauty.”

These works on view in our process space exemplify the cycle of construction and destruction taking place within the Spencer’s collection.