Archive Label 2003 (version 1):

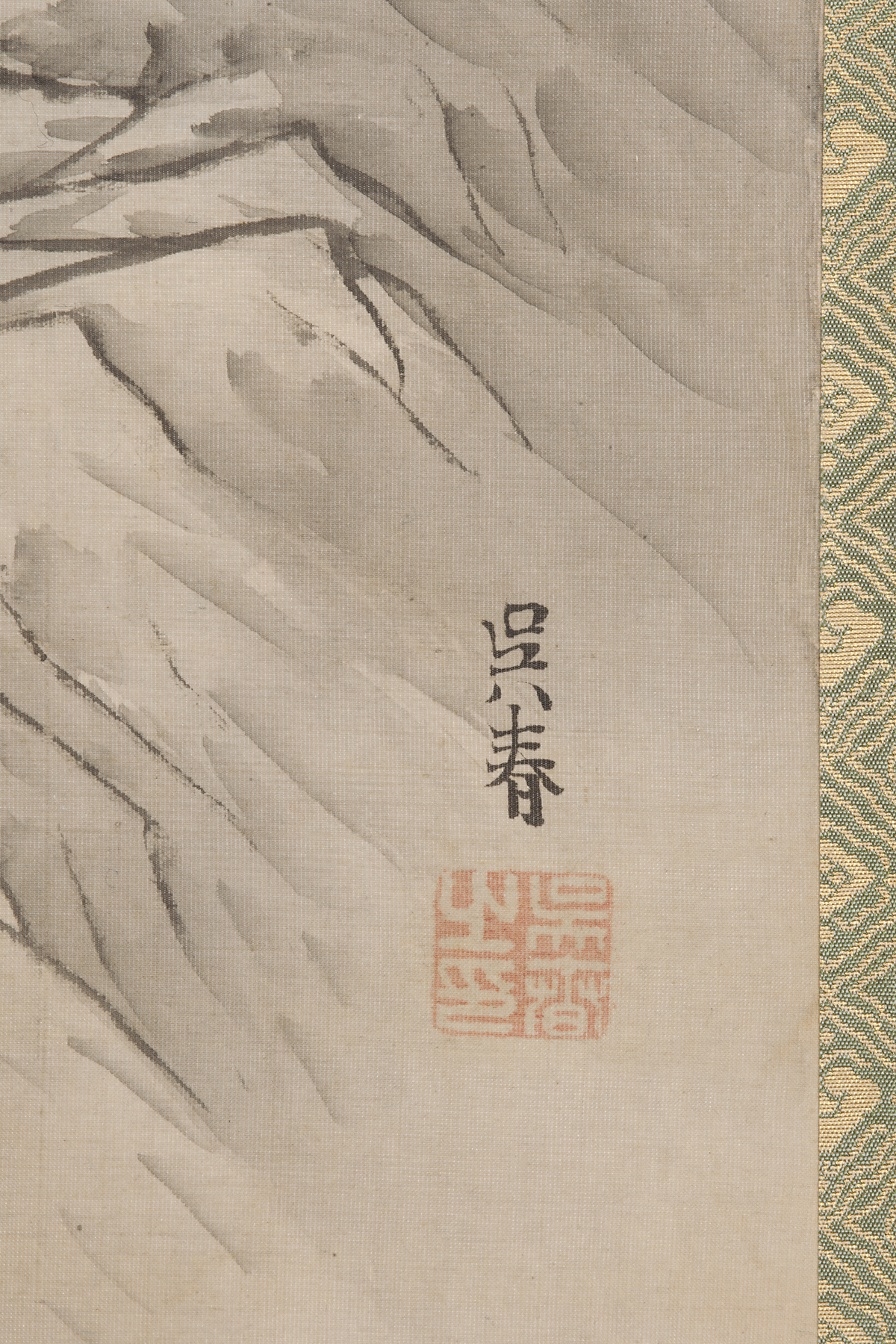

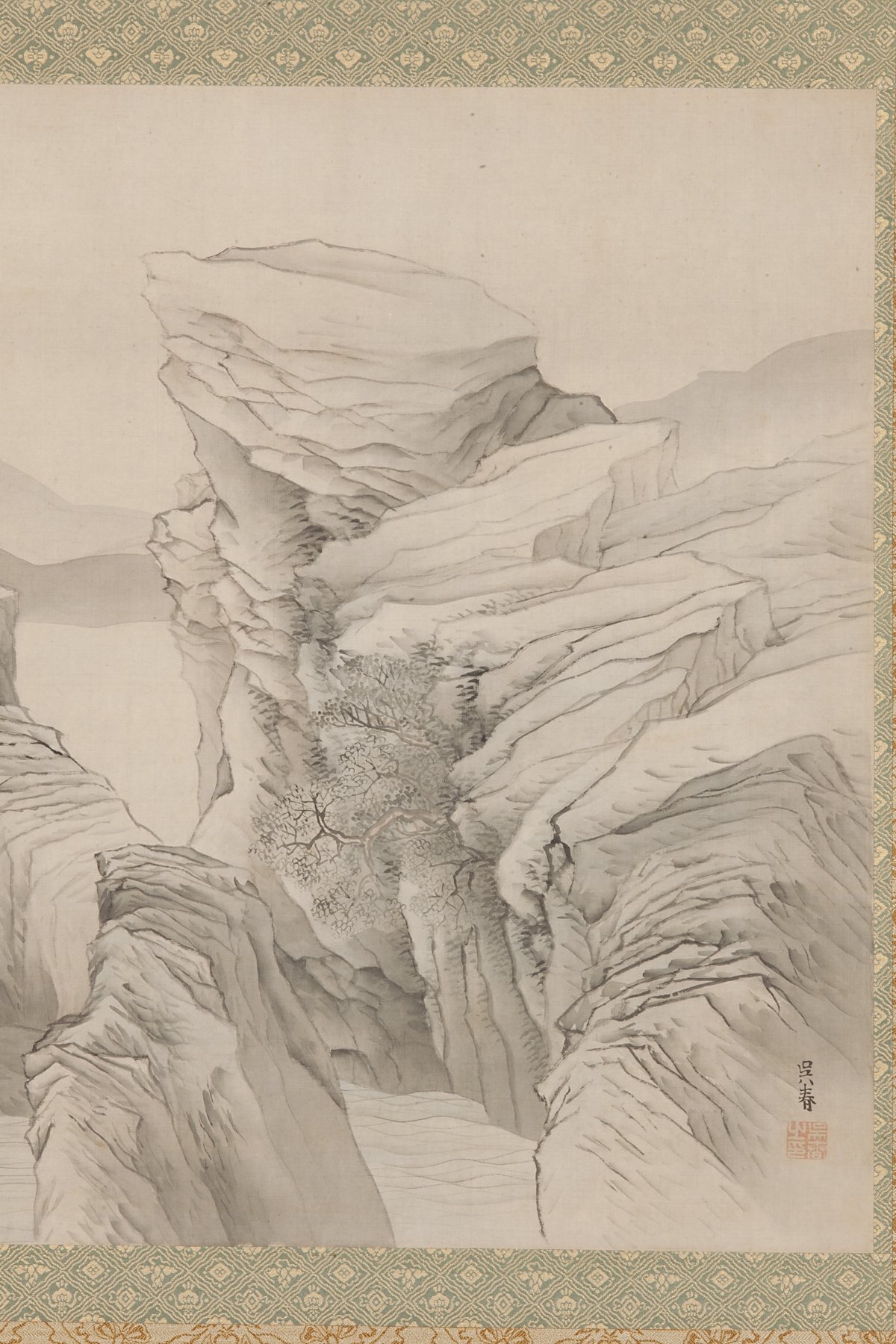

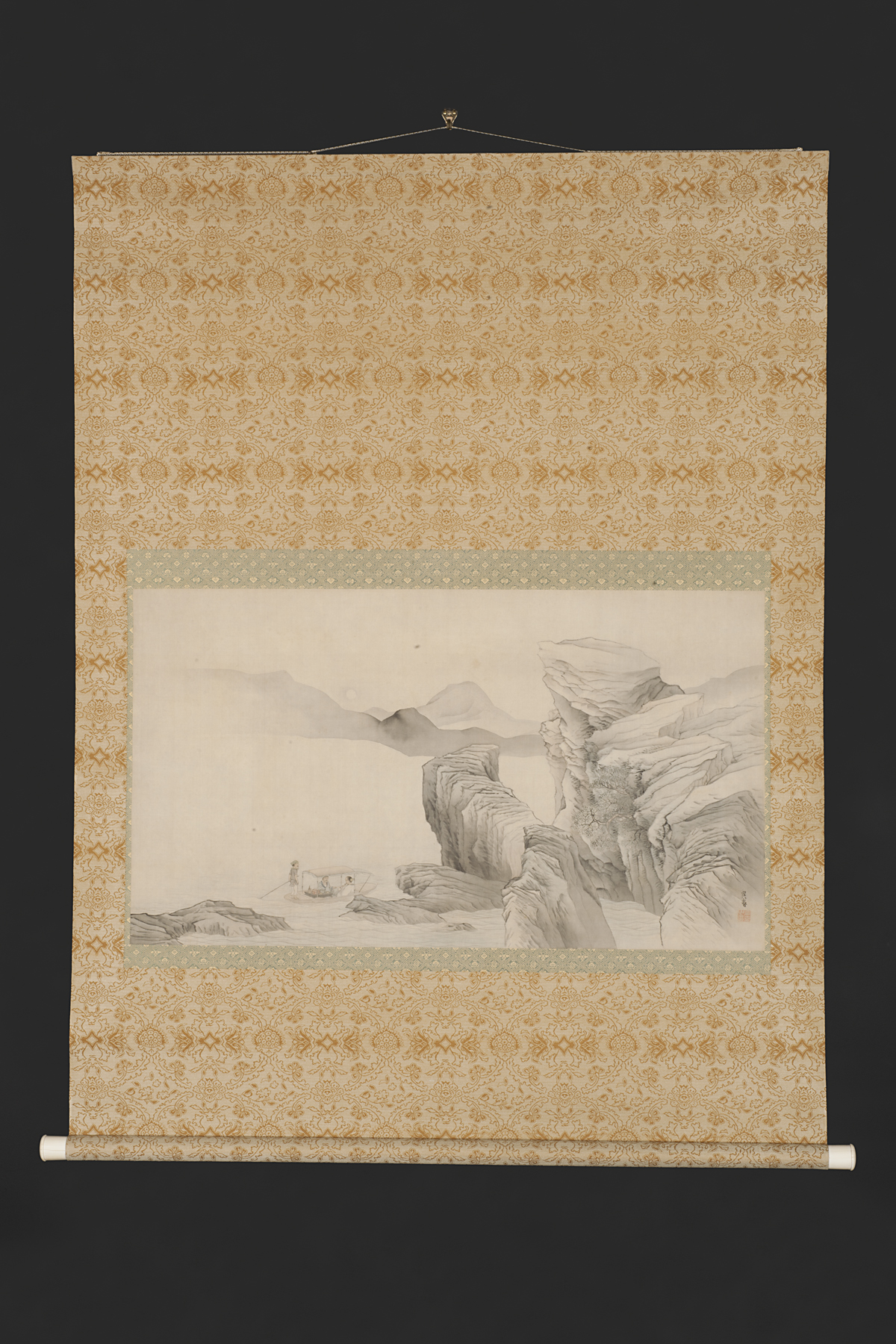

Goshun was trained by Yusa Buson (1716-1784), a renowned poet and painter of the Nanga or literati style, and later studied with Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), known for his skill at rendering perspective, volume, and other aspects of Western realistic depiction. Goshun’s later work, such as Red Cliff, skillfully combines the two styles of painting. Here, the subject matter and use of line to define form (especially in the rocky hillocks on the right side of the painting) derive from Nanga interests and techniques, while the sense of volume, the use of various tonalities of ink washes to define form, and the sense of perspective come from Goshun’s training with Okyo.

Archive Label 2003 (version 2):

The theme of this painting, ‘The Red Cliff,’ refers to a pair of poetic essays written in 1082 by the famed scholar, poet, and calligrapher Su Shi (1037-1101). The works reflect on themes of nostalgia, transience, and beauty and have inspired countless painters in East Asia over the centuries. In the first of the essays, illustrated here, Su and a friend have gone out on a boat see the scenic Red Cliff, compose poems, drink, converse, and enjoy the moon. Su is exhilarated, but his friend begins to play a mournful song on his flute. When asked why by Su, he replies that he was recalling an ancient hero, whose victory at the Red Cliff made him the greatest man of his time. Now, he lamented, the hero was all but forgotten. Su consoled his friend with these words. “If we look at things through the eyes of change, then there is no instant of stillness in all creation. But if we observe the changelessness of things, then we, like all beings, have no end…only the clear breeze over the river, or the bright moon between the hills, which our ears hear as music, our eyes see as beauty- these we may enjoy freely and they will never be exhausted.”

Matsumura Goshun has portrayed the moment when the friend plays the flute. The boat nears powerfully jagged cliffs, to which but a single tree clings. In the distance are mountains and the full autumn moon between the hills. The painting is a daring balance of contrasts: The cliffs, defined by calligraphic lines, fill the right side; the left side is empty space, with ink wash indicating the distant mountains. The figures and the boat, in a further contrast, are more naturalistically rendered. This combination of styles, characteristic of Goshun’s later work, became the basis for the Shijo school that he founded. It flourished, especially in Kyoto, well into the twentieth century.

Archive Label 2003 (version 3):

The painting is based on a famous poetic essay written by the literatus Su Shih (1037-1101). As the poet and a friend drifted by the Red Cliff, the friend played a melancholy air on his flute recalling an all-but-forgotten ancient hero who had won a major battle at Red Cliff. The poet responded:

We are no more than summer flies between heaven and earth, grains of millet on the waste of the sea…if we look at things through the eyes of change, then there is no instant of stillness in all creation. But if we observe the changelessness of things, then we like all beings have no end…only the clear breeze over the river, or the bright moon between the hills…

Exhibition Label:

"The Art of Stories Told," Jun-2004, Veronica de Jong

This painting depicts the personal account of Su Shi’s (1037-1101) trip with some friends to an historic site along a river in Hubei province. Their destination was the Red Cliff, a site where many lives were lost in a battle of the third century. In 1082 Su wrote two works titled “Red Cliff” and the first work is illustrated here. In this version, Su and his companions floated down a river enjoying wine while chanting poems to the bright, full moon. When a friend played a melancholy tune on his flute Su asked why he was sad. His friend replied he was thinking of the great hero who fought at the Red Cliff and who was almost forgotten despite his great victory. Su tried to console his friends with the following remarks: “If we look at things through the eyes of change, then there is no instant of stillness in all creation. But if we observe the changelessness of things, then we, like all beings, have no end... only the clear breeze over the river, or the bright moon between the hills, which our ears hear as music, our eyes see as beauty-these we may enjoy freely and they will never be exhausted.”

This scroll captures the plaintive moment when Su’s friend plays his flute as they float below jagged, almost barren cliffs. Their insignificance in relation to nature as told in the story is suggested by their diminutive size in comparison to the vast moonlit landscape.

Exhibition Label:

"Time/Frame," Jun-2008, Robert Fucci, Shuyun Ho, Lauren Kernes, Lara Kuykendall, Ellen C. Raimond, and Stephanie Teasley

On a beautiful moonlit autumn night in 1082, Su Shi (1037-1101) and his friend boated under the Red Cliff, a legendary ancient battlefield. Watching the waves washing away the marks of even the greatest heroes, his friend could not contain his grief for life’s brevity, and played a sad song on his flute. Su said to him, “Do you know how it is with the water and the moon? The water flows on and on like this, but somehow it never flows away. The moon waxes and wanes, and yet in the end it is the same moon. If we look at things through the eyes of change, then there’s not an instant of stillness in all creation. But if we observe the changelessness of things, then we and all beings alike have no end.” Su’s friend was pleased. (The First Prose of the Red Cliff, Su Shi, 1082.)