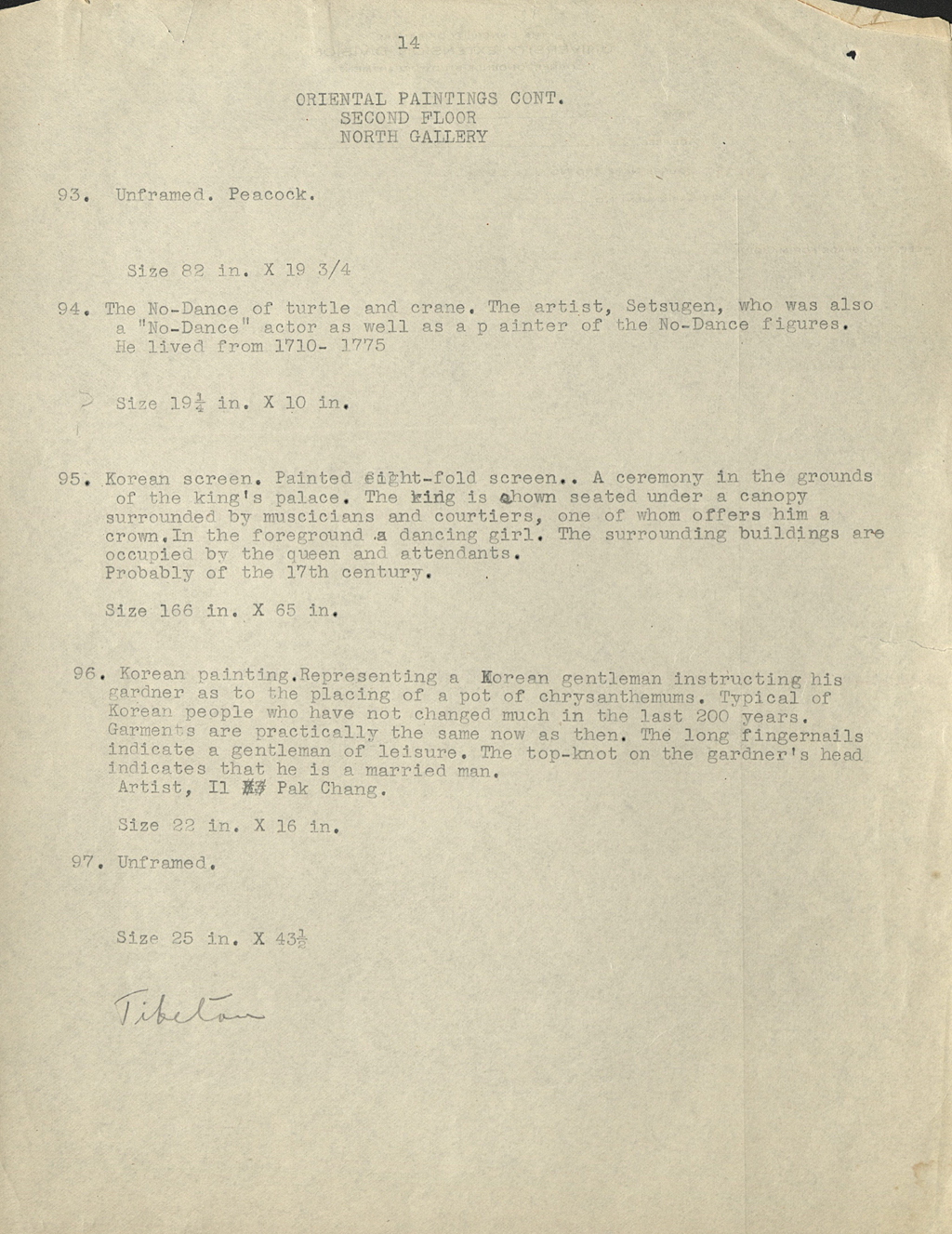

郭汾陽行樂圖 Gwakbunyang hyangrakdo (Guo Ziyi‘s Enjoyment-of-Life Banquet Screen), unknown maker from Korea

Artwork Overview

郭汾陽行樂圖 Gwakbunyang hyangrakdo (Guo Ziyi‘s Enjoyment-of-Life Banquet Screen)

, early 1800s, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910)

Where object was made: Korea

Material/technique: color; ink; silk

Credit line: William Bridges Thayer Memorial

Accession number: 2015.0061

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request