Bodies can be injured or sick, plagued by physical maladies, psychological distress, and social and environmental ills. People seek advice and interventions from healers of all kinds to tend to their bodies. In some cases, healing may entail medical doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, and prescription medication; in others it may require the treatments of religious practitioners, medicinal herbs, cultural connection, or even social protest. Healing does not always work, of course, and the encroachment of age—and ultimately death—is inevitable.

Western medicine is a relatively recent invention and is far from the only option for treating ill and ailing bodies. The works of art on this page decenter the Western tradition by exploring healing in its many forms, prompting us to ask: How have views about healing the body shifted through time and across cultures? What social, political, and economic dimensions accompany the treatment of the body, and how are they addressed—or ignored—in healing practices?

How can works of art encourage us to consider more inclusive ways of treating ourselves and one another?

The Ceiling Can’t Hold Us, Dylan Mortimer

60706 label

Dylan Mortimer was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis when he was three months old and has since received two double lung transplants. In this collage, Mortimer employs imagery that reflects his experiences with this chronic illness, using glitter to communicate the tenuous beauty and hope he finds in his ongoing healing. Abstract circular shapes represent healthy cells and form halos around his medical team, referencing his Christian faith and the important relationships that develop between patients and providers. The tangled pink branches symbolize the regeneration of the bronchial trees that form his lungs, even as he lies vulnerable and exposed on an operating table wearing Nike Air Max sneakers. This motif, which recurs throughout Mortimer’s work, reveals his childhood desire to own Air Max shoes and to have the air they contain in their soles inside his lungs. Explore additional examples of Mortimer’s work featuring Air Max shoes in the accompanying links.

“There is a story of a paralytic who is carried to Jesus for healing. The house is too crowded to even enter, so the patient is lowered through the roof. This is a rendition of that Biblical scene, a self-portrait in surgery. The room is filled with surgeons, care takers, and prayer warriors. It is an interior space, with a forest, that also feels like outer space. Cellular shapes form the strands that lower me down. It is an exercise in humility, vulnerability, and hope.”

Dylan Mortimer

untitled (Womba, version 2, RS9805), Renée Stout

Renee Stout label

As a child, Renée Stout was fascinated by minkisi (singular: nkisi) figures carved by the Kongo peoples of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Spiritually imbued minkisi contain sacred substances, including medicinal herbs the Kongo peoples believe can alleviate both physical maladies and social ills, such as poverty or crime. Decades later, these minkisi became a source of conceptual and visual inspiration for Womba, an imaginary character from Ibn, a fictional island where inhabitants believe that bones have the power to heal. Here, Womba dolls would be placed in the homes of sick individuals to cure their illnesses. Stout’s Womba prompts us to question the boundaries between what is true and false, real and imagined, scientific and artistic.

Child Taken by Mermaid, Melania Mazinyani

Child taken by mermaid label

When the Shona people of Zimbabwe need medical advice or spiritual guidance, they may seek out a n’anga—a traditional healer with the power to bless, harm, or restore health. This painting depicts a mythological narrative in which a young boy is transformed into a n’anga. The story begins in the upper left quadrant, where a woman conducts chores while her children play in a nearby body of water. When her son is snatched by a mermaid, the family seeks the guidance of an established n’anga, who advises them to brew beer and engage in ritual drumming to soothe the water spirit. These actions secure the return of their son, who emerges with the knowledge to be a n’anga himself. He is shown in his transformed state in the center of the painting wearing the red and white cloth skirt associated with this revered station.

Today, many Shona people still seek the advice of n’anga, who are often recognized and registered as part of the Zimbabwe National Traditional Healer’s Association, to cure their ailments. The donor, Sue Schuessler, conducted anthropological fieldwork with traditional Ndbele healers, known as n’goma, in Zimbabwe and collected this painting as part of her research.

藥師佛 Yaoshi fo (Medicine Buddha), unknown maker from China

Medicine buddha label

This representation of the Medicine Buddha can be identified by the fruit he holds in his left hand. The myrobalan (Terminalia chebula) is a small fruit found in South Asia that has long been revered for its healing properties. A seventh-century sutra, or teaching, recounts the twelve vows the Medicine Buddha made to help living beings after attaining enlightenment, including alleviating pain and disabilities, curing disease, and promoting optimal health. Since then, people have meditated with the mantra of the Medicine Buddha to overcome sickness and ease suffering for themselves or others. Meditation with this mantra is believed to purify the underlying karmic causes of diseases and cultivate holistic well-being. Meditation in general offers many health benefits, including the production of immune-boosting endorphins.

Dr. Karl Menninger

More than 500 objects in the Spencer’s collection came to the University of Kansas through Karl Menninger, an eminent psychiatrist who founded the Menninger Foundation and Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. Dr. Menninger was instrumental in destigmatizing mental illness by advocating for the science behind psychiatry. He also valued non-Western approaches to healing, especially those practiced by Native Americans, and amassed a significant collection of objects related to global healing that were displayed in clinical spaces and his private offices. The three following entries are a small sample of such objects.

Honan (badger katsina), unrecorded Hopi artist

Label text

medical bag, unrecorded Potawatomi artist

Label text

possible idiok mask, unrecorded Ibibio artist

Label text

Anorexia Girl, Jenny Schmid

Anorexia Girl label

The disproportionately large head of the character in this print represents the importance artist Jenny Schmid places on the psychological aspects of the image. Here, the central figure’s hollow eyes, sunken cheekbones, and visible ribs suggest that she struggles with anorexia nervosa, a serious eating disorder. Other details highlight the unrelenting and intrusive thoughts the girl has around body image, weight, and food: ghostly skeletons tantalize and mock her, offering calorie-laden cake and holding a mirror that reflects the girl’s distorted self-perception. In the upper right, a vignette shows a skeleton embracing a young woman from behind, referencing Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dance of Death woodcuts; other works in Healing, Knowing, Seeing the Body by Alfred Rethel and Sebald Beham make similar allusions. She sips from a cup emblazoned with the word “diet” to wash down pills that promise to make her “thin” and “thinner.” In the lower right, a grieving version of the girl clutches her own casket.

Schmid’s work provides a devastating look at the intersection of mental and physical health for those struggling with disordered eating. According to the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

Exorcising America: Mouth Exercises, Merritt Johnson

Mouth exercises label

Merritt Johnson’s ongoing video series Exorcising America exposes a range of issues facing Indigenous people. In Mouth Exercises, Johnson consumes an ice cream cone while commenting on the many forms of systemic abuse enacted on the bodies of Native people, including health disparities such as diabetes and heart disease. To foreground the ideas she’s communicating rather than the aesthetics of the work, she deliberately adopts the accessible DIY style of instructional YouTube videos. Although Johnson’s initially suggestive style of eating subtly references the sexualization and objectification of women (another common theme in her work), she soon begins spitting out the sweet dessert, pointing out the dangers of silence in the face of systematic bodily oppression.

Fetish (object/object/object), Merritt Johnson

Door between worlds (Animal), Merritt Johnson

Merritt Johnson text

These sculptures incorporate Indigenous materials and weaving techniques to make statements about both the power and powerlessness of women’s bodies. In Door between worlds (Animal), Johnson muses on the strength that comes with bringing new life into the world by framing a female pelvis as a literal passageway between one realm and another. Here, the female body is beautiful, resilient, and potent.

Fetish (object/object/object) presents a contrasting view. Here, a torso featuring breasts, fur, and teeth evokes some of the most fetishized areas of the female body; the absence of other body parts communicates the ways women are often reduced to objects. Johnson’s use of the word “object” three times in the title is significant, referring to its different definitions: a perceivable material form; something toward which thought, feeling, or action is directed; and disagreement, opposition, or distaste—the latter reflecting the diverse and outspoken opinions people have about women’s bodies.

View from the Ambulance, Dylan Mortimer

Mortimer label

As a cystic fibrosis patient, Dylan Mortimer finds ambulance doors an intriguing and “visually surprising” symbol of the tension that exists between trauma and hope for those living with chronic illnesses. This piece was inspired by Mortimer’s experience being transported by ambulance from Kansas City to St. Louis to receive his first double lung transplant. At the start of the ride, Mortimer took a photograph of the Kansas City landscape through the medical imagery on the ambulance doors, hoping that he would live to see it again. He created this work shortly after transplant, seeking to transform a tragic situation into something beautiful.

"Most of my work hangs in the tension between trauma and hope. This piece envisions a glory-filled light spectacle while in an ambulance riding towards an uncertain, but hopeful, future."

Dylan Mortimer

Eclipse, Gina Westergard

Gina label

The ceaseless cycle of life inspires University of Kansas faculty member Gina Westergard to create intricate funerary urns, such as Eclipse, that address a challenging topic we must all confront: death. Her artistic practice as a metalsmith typically entails making functional objects in which the user’s needs, wishes, and desires are considered at the point of creation. So too, she suggests, should funerary urns be made deliberately to invite storytelling and human connection. The minimalistic form and vibrant colors on the outside of Eclipse are meant to elicit the joy and beauty of a life lived, but the urn also opens to reveal more intricate interior spaces, new surfaces, and discrete objects. Westergard said these acts of discovery represent “new growth, renewal, and an energy that continues” even after death.

Other artists in this exhibition grapple with similar issues in their work. For instance, in her wearable sculpture Brain Cancer Headdress for Maro (1992), Athena Tacha transforms a private memorial into the public realm, encouraging reflection not only on death but also social ills, ecological threats, and even the exploitation of the female body through the fashion industry.

Reserving: Tuberculosis, Ruth Cuthand

Cuthand label

Through vibrant, intricate beadwork, First Nations artist Ruth Cuthand explores the historical connections among colonialism, race, and disease by depicting microscopic views of pathogens like tuberculosis, whooping cough, measles, HIV, and, most recently, Covid-19. Historically, infectious diseases disproportionately affected Indigenous communities, and similar health disparities continue today as a result of deep-seated inequity and ongoing systemic violence against Black and Indigenous populations and other people of color. Cuthand’s chosen medium further reflects this complex history. Like many infectious diseases, glass beads were first introduced in the Western Hemisphere by European colonizers who traded the inexpensive items for valuable furs and other goods; like infectious diseases, they fundamentally disrupted Indigenous ways of life.

Tuberculosis, the pathogen displayed here, bears particular relevance to Cuthand’s lived experience and artistic practice. She recalls: “As a child, my first art materials included the orange paper that was discarded in the processing of the Polaroid chest x-rays that we were subjected to annually as students in routine tuberculosis screenings; they collected the peculiar-smelling 18-inch squares of paper and gave them to my Anglican minister father for use in Sunday school.”

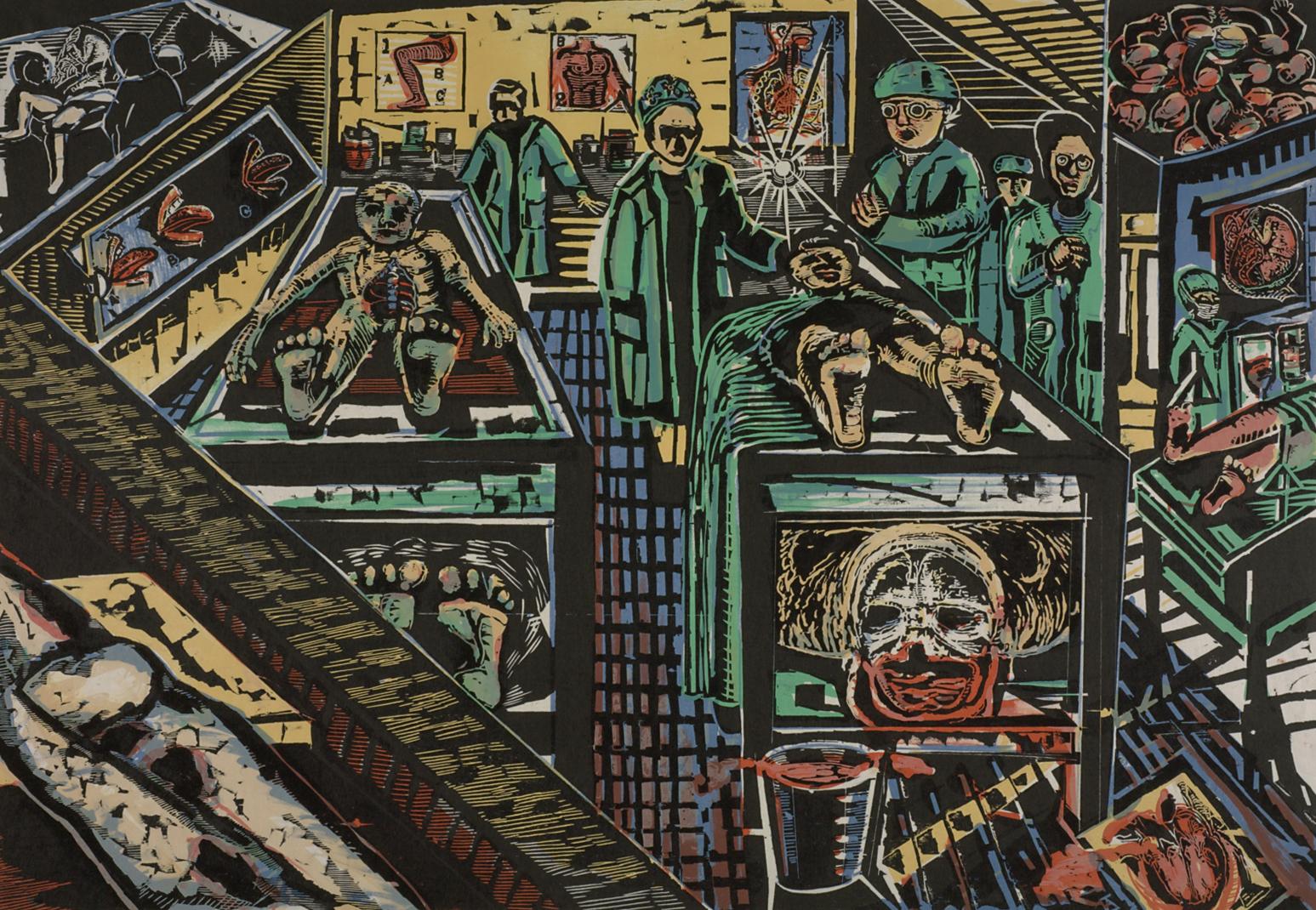

As It Is, Eric Avery; Bill Lagatutta; Peregrine Press

Eric Avery label

In his series Damn It, Dr. Eric Avery—a psychiatrist who worked on the front lines of the 1980s AIDS epidemic—documents a homosexual love story from its first encounter, subsequent AIDS diagnosis and illness, and, finally, the autopsy portrayed in As It Is. Each of the prints in the series references other works of art, from Albrecht Dürer’s The Bath House (1496) to Max Beckman’s The Morgue (1922), which provided the source imagery for this work. By drawing from this art historical narrative, Avery inserts the AIDS epidemic into a long global history of disease in order to destigmatize the illness and, in doing so, draw attention to the shared physical and spiritual struggles of love and death that unite us all.

Repurposed billboard west of Salina, Kansas along I-70 7/13/2014 – 1:40PM, Philip Heying

Heying label

In the grasslands outside Salina, Kansas, photographer Philip Heying was transfixed by a black and white billboard bearing a raw, public plea: “I need a kidney.” Heying learned that local resident Jim Nelson painted the message in a desperate effort to find a kidney donor for his wife Sharon Plucar after she failed to qualify for a spot on the official transplant list. Plucar passed away three months after Heying took this photograph. The image exposes flaws in the U.S. healthcare system and raises important questions about who can access it. Whether considered through the lens of economics, policy, or human rights, questions about bodily autonomy in healthcare are at the forefront of national conversations, especially as we grapple with new global health crises like Covid-19.

Embrace, Ingrid Bachmann

Bachman label

Montreal-based transdisciplinary artist Ingrid Bachmann is the Spencer Museum of Art’s 2020–2021 International Artist-in-Residence. After visiting the Spencer in January 2020, Bachmann was inspired to create an immersive installation that would use touch, sound, and texture to make visitors aware of their own bodies and bodily experiences. With Embrace, Bachmann juxtaposes monumental scale with soft, lush, conductive materials such as felt and copper to create discreet environments that, upon entry, create different sensory experiences. There are no clear thresholds, permitting free movement into and out of the spaces. In a time when discussions about our health and bodies are unrelenting, ever-changing, fast-moving, and often divisive, Embrace encourages you take a moment to contemplate your physicality in calmness and serenity.