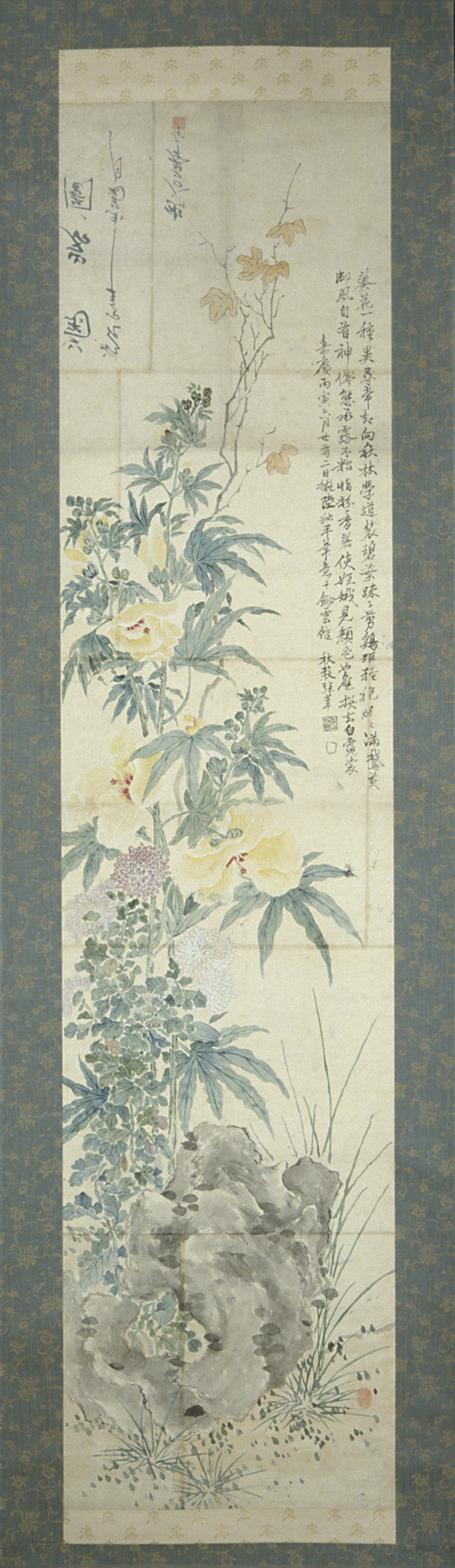

Mallows, Chrysanthemums and Rock, Noguchi Yūkoku

Artwork Overview

Noguchi Yūkoku, artist

1827–1898

Mallows, Chrysanthemums and Rock,

1871, Meiji period (1868–1912)

Where object was made: Japan

Material/technique: silk; color; ink

Dimensions:

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 133 x 31.3 cm

Mount Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 211 x 43.6 cm

Roller Dimensions (Width x Diameter): 49 cm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 52 3/8 x 12 5/16 in

Mount Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 83 1/16 x 17 3/16 in

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 133 x 31.3 cm

Mount Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 211 x 43.6 cm

Roller Dimensions (Width x Diameter): 49 cm

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 52 3/8 x 12 5/16 in

Mount Dimensions (Height x Width x Depth): 83 1/16 x 17 3/16 in

Credit line: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Hutchinson

Accession number: 1989.0106

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request