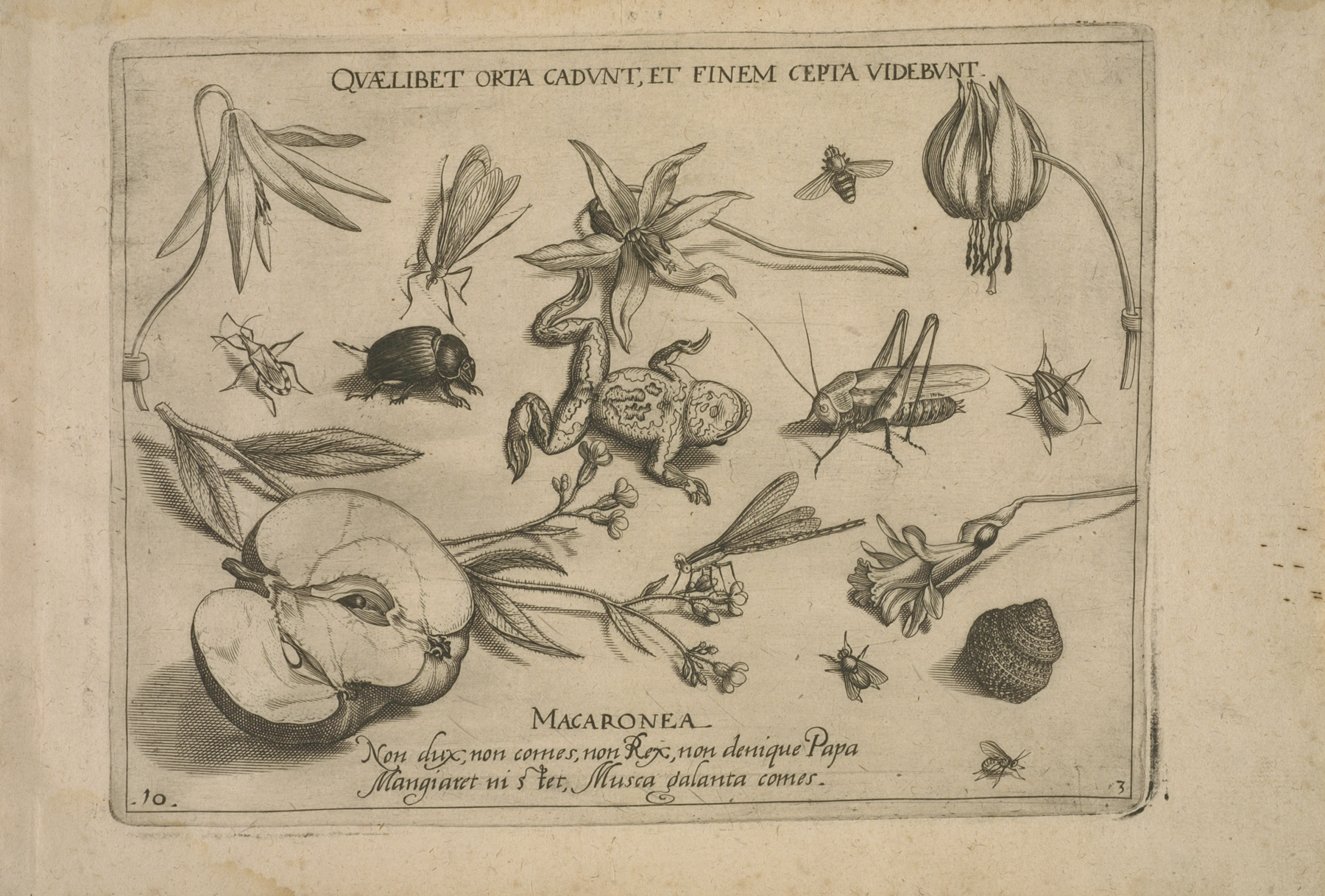

Part 3, plate 10: Riddle, Jacob Hoefnagel; Joris Hoefnagel

Artwork Overview

Jacob Hoefnagel, artist

1575–circa 1630

Joris Hoefnagel, artist

1542–1601

Part 3, plate 10: Riddle,

1592

Portfolio/Series title: Arcetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelli

Where object was made: Southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium)

Material/technique: engraving; laid paper

Dimensions:

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 158 x 208 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 186 x 273 mm

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 14 x 19 in

Image Dimensions Height/Width (Height x Width): 158 x 208 mm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 186 x 273 mm

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 14 x 19 in

Credit line: Museum purchase: Helen Foresman Spencer Art Acquisition Fund

Accession number: 2006.0020.04

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request