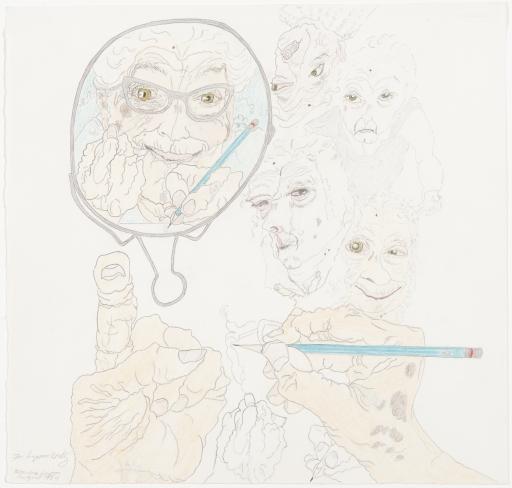

untitled, Elizabeth Layton

Artwork Overview

Elizabeth Layton, artist

1909–1993

untitled,

August 1984

Where object was made: United States

Material/technique: colored pencil; pencil

Dimensions:

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 30.2 x 31.6 cm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 11 7/8 x 12 7/16 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 16 x 20 in

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 30.2 x 31.6 cm

Sheet/Paper Dimensions (Height x Width): 11 7/8 x 12 7/16 in

Mat Dimensions (Height x Width): 16 x 20 in

Credit line: Gift of Lynn Bretz and Janet Hamburg

Accession number: 2011.0475

Not on display

If you wish to reproduce this image, please submit an image request