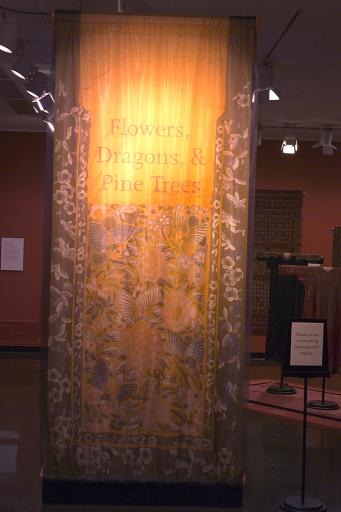

Flowers, Dragons, and Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art

Exhibition Overview

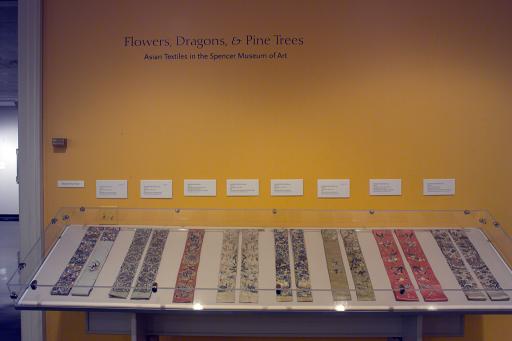

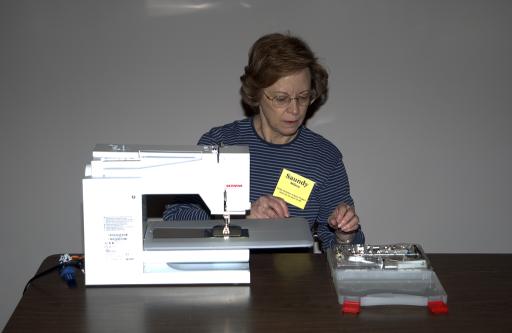

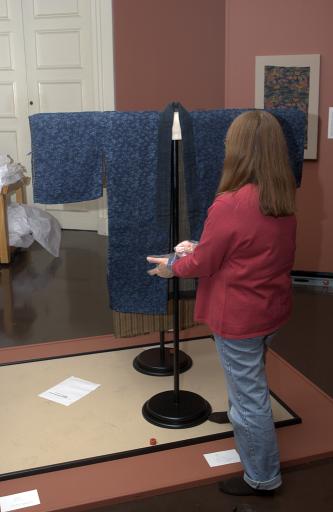

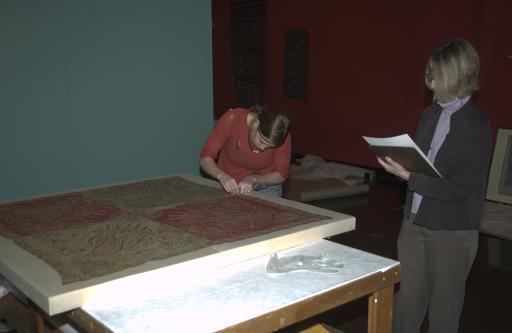

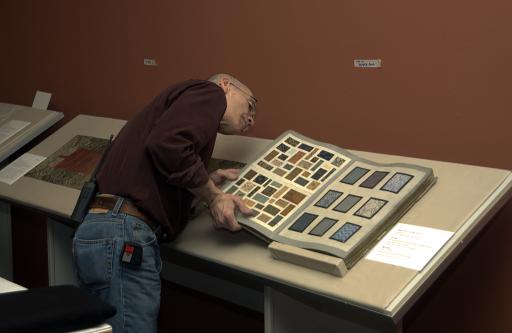

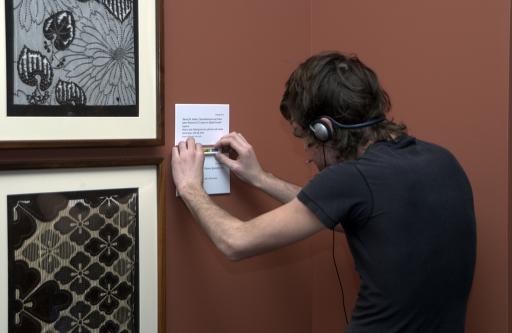

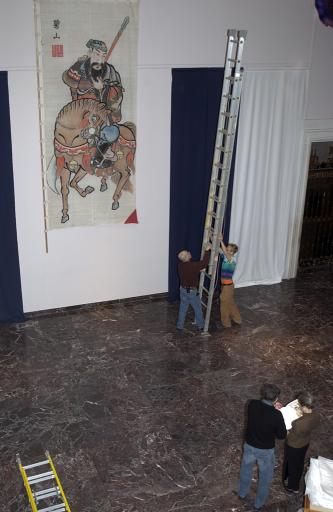

Stacked in boxes and accessible only by ladder, the Asian textile collection at the Spencer Museum was virtually hidden from public view for almost eighty years. Flowers, Dragons, & Pine Trees is the result of fifteen years of quiet work behind the scenes to research, clean, conserve, re-house, photograph, publish and exhibit this little known section of the museum's collections.

The exhibition focuses on 90 textiles from India, Iran, China and Japan, including:

* Persian velvets and brocades Kashmir shawls Embroideries of northwest India and Pakistan Chinese court/official costume and Han and Manchu women's formal and informal dress Buddhist and Daoist costume and temple furnishings

* Japanese cotton and bast fiber costume, furnishings, and festival textiles

The core of the Asian textile collection was part of Sallie Casey Thayer's original 1917 gift to the University of Kansas of 7,500 objects of Western and Asian art--a gift that founded the KU art museum. Throughout the twentieth century, the Asian textile collection grew almost exclusively through occasional gifts--some magnificent, others modest--until the 1990s, when the museum actively began to seek out a few key objects. In Asia, textiles were important. Worth their weight in gold, luxury silks traversed the trade routes that linked East Asia with the Mediterranean, carrying technical knowledge and new design ideas within their structures. A venerated Buddhist abbot's robe was believed to incorporate his essence and, long after his death, was preserved as a sacred treasure by his followers. In northwest India, women embellished and protected their households and family with layers of embroidered textiles whose strong colors and vibrant patterns stood in sharp contrast to the surrounding desert. A lively interplay (and competition) between designers and craftsmen in Kashmir, France, and Great Britain transformed a simple man's sash into the opulent woman's Kashmir shawl that remained at the height of fashion for an astonishing 75 years, throughout most of the nineteenth century.

The Spencer's Asian textile collection represents great geographical breadth as well as diversity of function, technique, and patronage. The approximately 300 objects include court, merchant, military, theatrical, and folk costume, temple and household furnishings, and numerous discrete pieces of complex weaving, embroidery, and dyeing. The textiles range in date from the fifteenth to the late twentieth century. The largest number come from China, followed by Japan, the Indian subcontinent, Iran, Indonesia, Central and West Asia, and Korea.

The exhibition is made possible by the generosity of the David Woods Kemper Memorial Foundation, the Breidenthal-Snyder Foundation, Dave and Gunda Hiebert, the Kansas Arts Commission, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. Additional support provided by corporate sponsor The World Company. The Spencer also received a great deal of support for conserving, researching, photographing and publishing the collection. We are grateful to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Japan Foundation, the Getty Grant Program, the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and the Blakemore Foundation. A complete catalogue of the Spencer's Asian textiles collection, authored by Mary M. Dusenbury, guest curator of Asian art and organizer of the Flowers, Dragons, & Pine Trees exhibition, was published in fall 2004 by Hudson Hills Press and is available for purchase in the Spencer's Museum Shop

This exhibition was organized for the Spencer Museum of Art by guest curator Mary Dusenbury in conjunction with the publication Flowers, Dragons and Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art published by Hudson Hills Press. The exhibition is funded in part by the David Woods Kemper Memorial Foundation, Breidenthal-Snyder Foundation, and Dave and Gunda Hiebert.

The World Company, Corporate Sponsor.

Comprising some three hundred objects, the collection of Asian textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas has remained a hidden treasure since its inception nearly a century ago. This small but important collection, which includes textiles from East, South, and Central Asia dating from the fifteenth through twentieth centuries, displays remarkable geographical breadth, great diversity of technique, and a broad range of functions. With highlights including late Persian textiles, Indian embroideries, Kashmir shawls, Chinese court costume, and Japanese folk garments, the Spencer's Asian textiles are rich in history and design, offering a wealth of information and beauty.

The Spencer's South Asian textiles represent both the consummate skill of professional craftsmen and the vivacity of folk designs. The latter may be seen in profusion on the embroideries of Northwest India and Pakistan, while the former is embodied in the Kashmir shawl, the fine garment of meticulous workmanship that swept Europe by storm in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

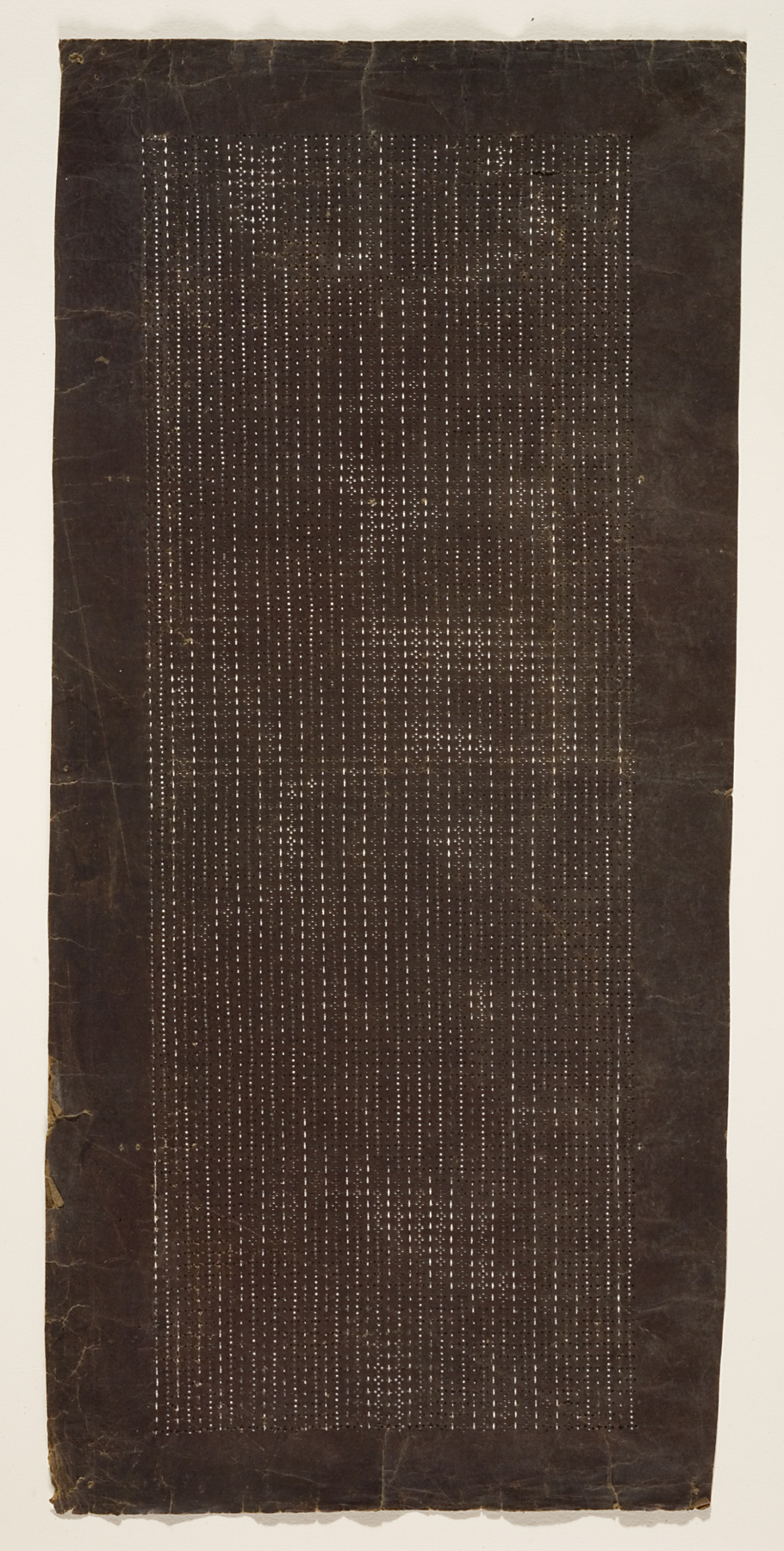

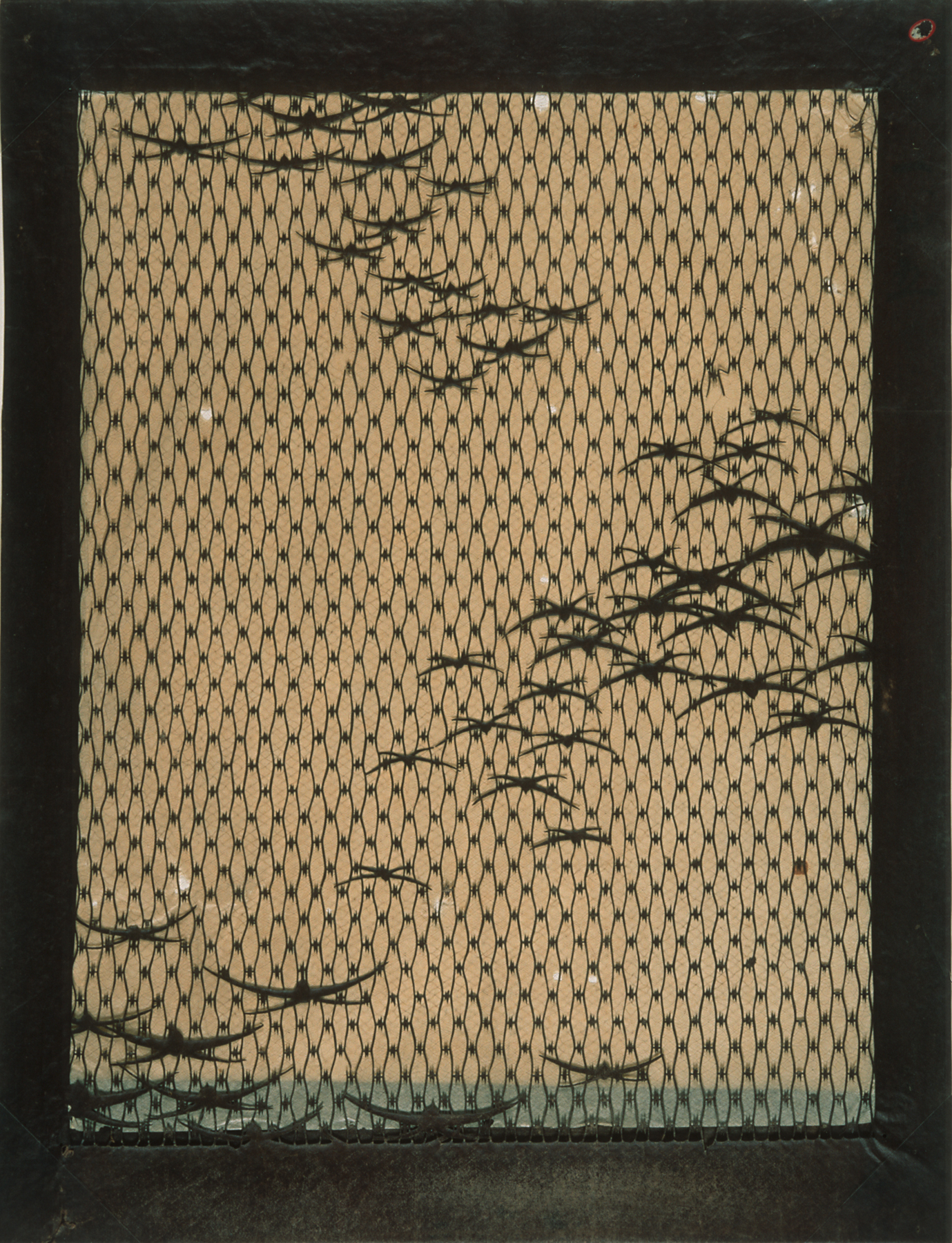

Chinese textiles, with nearly 140 pieces, form the single largest group of Asian textiles in the collection. The court robes and rank badges, women's garments, sleeve bands and other objects also share a profound visual language of great antiquity, with symbols drawn from Buddhism, Daoism, and native folk belief. Many of these symbols are also found on Japanese textiles, although simple, geometrically patterned garments of indigo-dyed cotton or hemp form an equally important and interesting part of this group. Innovative and unique dyeing methods, used on a variety of garment types, futon covers and other accessories, are hallmark of Japanese textile design, while bast fibers and distinctive stitching techniques characterize the textile traditions of rural areas far from the capital.